Category: Today in History

June 9

1954

Senator McCarthy is rebuked

After being wartime allies, the relationship between the Soviet Union and the western democracies degenerated into a Cold War which resulted in both sides maintaining huge armies facing each other in central Europe. Back in North America, the Igor Gouzenko revelations pointed to Americans working as Russian spies in the US and spoke of Americans with loyalties wider than just their native land. Coupled with Soviet expansionism in Europe and the growing power of the Communist Party of China versus wartime US ally Chiang Kai-shek, dislike of communism again took root. The crusade against Reds was first led by HUAC, the Congressional House Un-American Activities Committee, which dated from before the war but which was in 1945 made a powerful standing committee of the House with wide-ranging powers of investigation. Though HUAC had failed miserably in showing any real communist penetration of the movies, this attack on the so-called Hollywood Ten silenced the protests from the entertainment industry, created a blacklist of writers and performers whose careers were ruined, and set the stage for an anti-communist witch-hunt of government officials.

Anti-communist groups, such as the American Legion and firms of private investigators specializing in loyalty checks, spread stories about secret battalions of 75,- 80,000 trained communists manipulating a million leftist dupes, camp followers, and fellow travellers. Neighbourhood anti-communist watch groups were formed, sponsors of suspected programs or radio personalities were threatened with boycotts, libraries were scoured for leftist comics and books. This anti-communist mood forced a reluctant President Truman to institute government actions against federally-employed suspects. Loyalty boards screened civil servants and army personnel, firing many, not for disloyalty or treachery, but for once having belonged to left-wing causes or parties. Sensational cases included that of civil servant Alger Hiss whom Congressman Richard Nixon accused on television of spying for the USSR — Hiss denied it but was ruined; Nixon was launched into national prominence and was made Eisenhower’s V-P candidate in 1952 election.

This paved the way for further probes — the Rosenberg spy case sentenced Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to the electric chair for passing on nuclear secrets to the Soviets who had soon produced the A-bomb and the H-bomb with help from such spies — and convinced some politicians that the way to popularity with the voters was by denunciation of hidden communists. The leading proponent of this was the Senator from Wisconsin Joe McCarthy who in 1950 began announcing he had a list of red agents in the State department. The State Department was widely blamed for the failure of the US to support Chiang Kai-shek and the subsequent loss of China to the Communists, and though McCarthy’s accusations were usually drunken ramblings and without substance, they did create a climate of fear and an atmosphere of what became known as McCarthyism: guilt by association, intimidation of witnesses and abuse of democratic process. He announced that he had discovered that 30,000 books in USIS libraries abroad were by Communist or pro-Communist writers: Sovietolators as they were called and he succeeded in panicking officials wherever his gaze lighted. His success lay in using television and mobilizing grass-roots anti-intellectualism and xenophobia and distrust of the university-trained, upper-class, anglo-Protestant elite in government as well as their urbanized, educated Jewish counterparts. His downfall came when he attacked the US Army for sheltering communists — the establishment which had hitherto been timid came forth to denounce him and his alcoholic excesses caught up with him. On this day in 1954, Joseph Welch the attorney representing the Army lashed out at McCarthy, asking him in front of the television cameras: “You’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?”

By December 1954 his colleagues in the Senate censured him for his behaviour; his reign had ended and he was not re-elected for a third term. But consider this: McCarthy succeeded in his crusade though he himself was brought down. He helped discredit leftist policies and officials left over from the Roosevelt era; he redefined political discourse in terms of “American-mindedness” and even his left-wing opponents had to claim that they themselves had espoused “Americanism” for years. The labour movement had to move to the right. In 1950 the CIO expelled 11 national unions, 20% of its own membership, for alleged Communist leadership. Just a few months before his downfall in 1954 a supporter of McCarthy wrote this in a magazine article: “As Russia and Red China advance nightmarishly toward the maximum power goals which they will reach in the 1970s, the American people will be as unlikely to think seriously of anything else, as to ignore an onrushing comet. Communism will be the issue of the 1950s and sixties. Those American leaders who most surely interpret the emotions of the American public in the face of the Communist challenge will be the man who will dominate American politics. Today Senator McCarthy is the articulate voice of the American people in a Communist-haunted age. On this issue he marches with history. He cannot lose.”

June 8

1776 The Battle of Trois-Rivières

1776 The Battle of Trois-Rivières

One often hears the phrase “the thirteen colonies” in reference to the American Revolution but little is heard of the attempt by the armies of those rebels to coerce the inhabitants of other British North American possessions to heed the siren call of republicanism and disobedience to the crown. Even in Canada little attention is paid to the battles that thwarted the ambitions of the Continental Congress. One such battle occurred at Trois Rivières (aka Three Rivers), a town on the St Lawrence River between Montreal and Quebec City.

The so-called “Continental Army” had invaded Canada in 1775, expecting to be greeted favourably by French-Canadians eager to cast off the British yoke that had been laid on them for more than 25 years. Though the American force found a few anti-clerical and radical inhabitants, the vast majority was indifferent to the intruders or downright hostile. Montreal was captured — and the first printing press in Canada was established by Benjamin Franklin — but the siege of Quebec was a failure. By the spring of 1776 the American army was in retreat. On its way back to New York it encountered what they believed to be a small British force at Trois-Rivières, unaware that the redcoats had been strongly reinforced. A local guide led the Americans into a swamp and when they emerged they found themselves caught between the cannons of a British warship on the river and thousands of British regulars. The result was a nasty defeat for those who stood and fought. Thirty to fifty Americans were killed and over 200 captured. The rest straggled back to safety where the defeat was hotly debated and incompetent officers cashiered.

Many American wounded soldiers were treated at the Ursuline convent in Trois-Rivières. Congress never authorized payment for these services but the convent retained the bill. By the early 21st century, the original bill of about £26 was, thanks to the magic of compound interest, estimated to be equivalent to between ten and twenty million Canadian dollars. On July 4, 2009, during festivities marking the town’s 375th anniversary, American Consul-General David Fetter symbolically repaid the debt to the Ursulines with a payment of C$130.

June 6

1944 D-Day

By 1944 German forces were being pushed back on the Eastern Front and in Italy, but everyone knew that the Allies were preparing an invasion of continental Europe from bases in England. The Germans had constructed the massive Western Wall stretching from Norway to Spain, trusting to its minefields, beach obstacles, gun emplacements, and concrete bunkers to pin any invaders on the beach and deter any progress inland. The Allies relied on deception and air superiority to keep the enemy from knowing where their blow would be struck and from moving in reinforcements.

By 1944 German forces were being pushed back on the Eastern Front and in Italy, but everyone knew that the Allies were preparing an invasion of continental Europe from bases in England. The Germans had constructed the massive Western Wall stretching from Norway to Spain, trusting to its minefields, beach obstacles, gun emplacements, and concrete bunkers to pin any invaders on the beach and deter any progress inland. The Allies relied on deception and air superiority to keep the enemy from knowing where their blow would be struck and from moving in reinforcements.

On the morning of June 6, over 20,000 Canadian, British, and American paratroopers were dropped over the Normandy peninsula to take control of bridges and roads behind the landing zones. A thousand warships then bombarded defenders along a fifty-mile stretch of the coast, and units of the French Resistance were activated on missions of sabotage. Almost 7,000 vessels from 8 Allied navies, from battleships to landing craft, converged on 5 beaches, codenamed Utah and Omaha (the objectives of American forces) and Sword, Juno, and Gold (targets of Canadian and British armies).

Casualties were heavy. Americans suffered the most in terms of total numbers; Canadians lost most proportionately; the paratroop and glider attacks took a heavier toll than any of the beach landings.

Casualties were heavy. Americans suffered the most in terms of total numbers; Canadians lost most proportionately; the paratroop and glider attacks took a heavier toll than any of the beach landings.

None of the initial objectives were reached on the first day, but a successful toehold in France had been achieved and would provide the beachhead for the armies that would soon sweep the Germans out of France.

June 4

1783

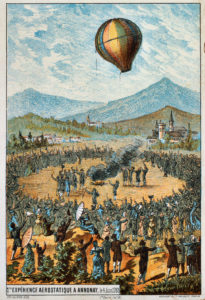

The Montgolfier Brothers make a hot-air balloon ascent

Joseph-Michel Montgolfier (1740 – 1810) and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier (1745 – 1799) developed a balloon made of sackcloth and paper, propelled by hot air. The younger brother made the first human ascent in a balloon in front of a large crowd of French dignitaries at Annonany in southeastern France. The journey lasted about 10 minutes, with the craft reaching an altitude of perhaps a mile. This led to further, more ambitious attempts. Those interested in this subject will learn almost nothing about it in the Monty Python sketch below.

June 3

1839 Commissioner Lin destroys the opium

In the early 19th century the Qing dynasty ruling China was trying to keep foreigners at bay and closely regulate trade with the outside world. This policy resulted in a balance of payments problem for the British who imported far more Chinese goods than the value of what they could, with difficulty, sell the Chinese. In response to this, the British East India Company hit on the diabolical scheme of smuggling opium into southern China, a technique that soon created a widespread addiction problem among the Chinese and a profitable harvest of silver for the British.

To remedy this, Emperor Daoguang sent Lin Zexu as a specially appointed imperial commissioner to end the practice of the opium trade. To stamp out opium, Commissioner Lin used all the powers of the Chinese state: he instituted a public-health program warning of the dangers of addiction; he organized addicts into five-man mutual-responsibility teams pledged to guarantee that no one in the group would smoke; he rewarded those informing on the drug pushers; he arrested dealers and seized their wares — tons of opium and tens of thousands of pipes.

He moved diplomatically with the foreigners behind the trade, not wishing to start a war he could not win, urging them to stick to their legitimate trade in tea, silk, and rhubarb (he believed this last to be essential to the health of foreigners) and to desist from harming the Chinese people. In a carefully phrased letter to Queen Victoria, Lin tried to appeal to her moral sense of responsibility. “We have heard that in your honorable nation, too,” wrote Lin, “the people are not permitted to smoke the drug, and that offenders in this particular expose themselves to sure punishment…. In order to remove the source of the evil thoroughly, would it not be better to prohibit its sale and manufacture rather than merely prohibit its consumption?” Opium in fact was not prohibited in Britain and was taken— often in the form of laudanum—by several well-known figures, Samuel Taylor Coleridge among them. Many Englishmen regarded opium as less harmful than alcohol, and Lin’s moral exhortations fell on deaf ears.

When the British in Canton refused to give up their opium, or to hand over only token amounts, he blockaded their compound. After six weeks, when the foreigners had agreed to give up over 20,000 chests of opium and Commissioner Lin had taken delivery, the blockade was lifted. Lin was now faced with the remarkable challenge of destroying close to 3 million pounds of raw opium. His solution was to order the digging of three huge trenches, 7 feet deep and 150 feet long. Thereafter, five hundred laborers, supervised by sixty officials, broke up the large balls of raw opium and mixed them with water, salt, and lime until the opium dissolved. Then, as large crowds of Chinese and foreigners looked on, the murky mixture was flushed out into a neighboring creek, and so reached the sea.

In a special prayer on June 3, 1839, to the spirit of the Southern Sea, “you who wash away all stains and cleanse all impurities,” Lin brooded over the fact that “poison has been allowed to creep in unchecked till at last barbarian smoke fills the market.” He apologized to the spirit for filling its domain with this noxious mixture and, he wrote in his diary, advised it “to tell the creatures of the water to move away for a time, to avoid being contaminated.” As to the foreigners who had lived through the blockade and now watched the solemn proceedings, Lin wrote in a memorial to Emperor Daoguang, they “do not dare show any disrespect, and indeed I should judge from their attitudes that they have the decency to feel heartily ashamed.”

On the contrary, the shameless British appealed to their government who used Lin’s actions as a pretext for the start of the Opium Wars that blasted the doors open to Chinese trade.

June 2

1581

The execution of James Douglas

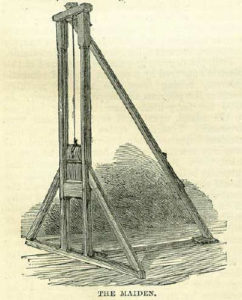

James Douglas, Earl of Morton (1516-1581) was a Scottish politician at a time when losing favour often meant losing one’s head. During the reign of Mary, Queen of Scots, he had sided with Protestant nobles supporting England and frustrating many of the queen’s actions. He had taken part in the murder of Mary’s favourite, David Rizzio, and was part of the army that compelled the queen to abdicate in favour of her baby son James. In 1572 he was named Regent, governing on behalf of James VI but he made enemies in the Scottish church and other noble factions. He was charged with the murder of Mary’s second husband Lord Darnley (who was blown up and strangled in 1567) and was executed by means of a guillotine-like device, nicknamed “The Maiden” which he had imported from England, based on the contraption used in Halifax, Yorkshire.

Holinshed’s Chronicle of 1587 describes the Halifax prototype of the guillotine and the curious law that made one susceptible to its embrace:

There is and hath been of ancient time a law, or rather a custom, at Halifax, that whosoever doth commit any felony, and is taken with the same, or confess the fact upon examination, if it be valued by four constables to amount to the sum of thirteen-pence halfpenny, he is forthwith beheaded upon one of the next market days (which fall usually upon the Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays), or else upon the same day that he is so convicted, if market be then holden. The engine wherewith the execution is done is a square block of wood, of the length of four feet and a half, which doth ride up and down in a slot, rabet, or regall, between two pieces of timber that are framed and set upright, of five yards in height.

In the nether end of the sliding block is an axe, keyed or fastened with an iron into the wood, which, being drawn up to the top of the frame, is there fastened by a wooden pin (with a notch made into the same, after the manner of a Samson’s post), unto the middest of which pin also there is a long rope fastened, that cometh down among the people; so that when the offender hath made his confession, and hath laid his neck over the nethermost block, every man there present doth either take hold of the rope (or putteth forth his arm so near to the same as he can get, in token that he is willing to see justice executed), and pulling out the pin in this manner, the head block wherein the axe is fastened doth fall down with such a violence, that if the neck of the transgressor were so big as that of a bull, it should be cut in sunder at a stroke, and roll from the body by an huge distance. If it be so that the offender be apprehended for an ox, sheep, kine, horse, or any such cattle, the self beast or other of the same kind shall have the end of the rope tied somewhere unto them, so that they being driven, do draw out the pin whereby the offender is executed.

June 1

1794 “The Glorious First of June”

We should need to bring back the horrors of the first French Revolution to enable us to understand the wild delight with which Lord Howe’s victory, in 1794, was regarded in England. A king, a queen, and a princess guillotined in France, a reign of terror prevailing in that country, and a war threatening half the monarchs in Europe, had impressed the English with an intense desire to thwart the republicans. Our army was badly organized and badly generalled in those days; but the navy was in all its glory. In April 1794, Lord Howe, as Admiral-in-Chief of the Channel fleet, went out to look after the French fleet at Brest, and a great French convoy known to be expected from America and the West Indies. He had with him twenty-six sail of the line, and five frigates. For some weeks the fleet was in the Atlantic, baffled by foggy weather in the attempt to discover the enemy; but towards the close of May the two fleets sighted each other, and a great naval battle became imminent. The French admirals had often before avoided when possible a close contest with the English; but on this occasion Admiral Villaret de Joyeuse, knowing that a convoy of enormous value was at stake, determined to meet his formidable opponent. The two fleets were about equal in the number of ships; but the French had the advantage in number of guns, weight of metal, and number of men. On the 1st of June, Howe achieved a great victory over Villaret, the details of which are given in all the histories of the period.

We should need to bring back the horrors of the first French Revolution to enable us to understand the wild delight with which Lord Howe’s victory, in 1794, was regarded in England. A king, a queen, and a princess guillotined in France, a reign of terror prevailing in that country, and a war threatening half the monarchs in Europe, had impressed the English with an intense desire to thwart the republicans. Our army was badly organized and badly generalled in those days; but the navy was in all its glory. In April 1794, Lord Howe, as Admiral-in-Chief of the Channel fleet, went out to look after the French fleet at Brest, and a great French convoy known to be expected from America and the West Indies. He had with him twenty-six sail of the line, and five frigates. For some weeks the fleet was in the Atlantic, baffled by foggy weather in the attempt to discover the enemy; but towards the close of May the two fleets sighted each other, and a great naval battle became imminent. The French admirals had often before avoided when possible a close contest with the English; but on this occasion Admiral Villaret de Joyeuse, knowing that a convoy of enormous value was at stake, determined to meet his formidable opponent. The two fleets were about equal in the number of ships; but the French had the advantage in number of guns, weight of metal, and number of men. On the 1st of June, Howe achieved a great victory over Villaret, the details of which are given in all the histories of the period.

Thus reads a nineteenth-century account of Howe’s victory. The French, not unnaturally, view the battle differently. Though it was a tactical loss for them, the vital grain convoy made it safely through to France where it was greeted with jubilation and public parades and Admiral Villaret de Joyeuse was promoted.

May 30

1972

Lod Airport Massacre

The next time you fuss about airport security, remember that it was once possible to board an airplane carrying an assault rifle and explosives. On May 30, 1972 three Japanese travellers stepped off a flight from Rome at Lod Airport in Israel, took out their weapons from violin cases and indiscriminately sprayed fire into the crowd. 26 people were killed, most of them Puerto Rican pilgrims, and 80 were injured. Two of the terrorists were killed on the spot but the third was captured.

What were Japanese Red Army communists doing involving themselves in the Palestine-Israeli conflict? It appears that an exchange program had been worked out with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine — External Operations, a more radical offshoot of the already pretty radical PFLP, led by Wadie Haddad. Haddad, an associate of Carlos the Jackal, was experienced in airliner terror, having master-minded the Entebbe high-jacking. The PFLP-OE trained the Japanese in Lebanon, thinking, correctly, that they would be less likely to draw suspicion from airline security.

The surviving attacker, Kozo Okamoto, pled guilty to murder charges and was sentenced to an Israeli jail but he was released in a prisoner swap in 1985. He is reported to have converted to Islam and lives in Lebanon, which has resisted calls for his extradition.

May 28

A day of two maritime disasters.

1558 The Spanish Armada sets sail

Philip II of Spain was determined to end the rule of Elizabeth I and her Protestant regime. He had waited until the death of Mary Queen of Scots (a rival claimant to the English throne) before starting military operations against England, so that he, or another member of the Habsburg clan, could rule the country. The plan was to assemble an enormous fleet to seize control of the English Channel and provide cover for an invading army to be ferried over on barges from the Low Countries. Ships of the Spanish and Portuguese navies, as well as dozens of others that could be commandeered or hired, gathered in Lisbon and on this date the first of 130 ships set sail. Galleons, galleasses, caravels, naos, pataches, pinnaces, carracks, supply hulks and even (madness!) galleys carried 8,766 sailors, 21,556 soldiers, and 2,088 convict rowers. Over half the ships never returned home.

Philip II of Spain was determined to end the rule of Elizabeth I and her Protestant regime. He had waited until the death of Mary Queen of Scots (a rival claimant to the English throne) before starting military operations against England, so that he, or another member of the Habsburg clan, could rule the country. The plan was to assemble an enormous fleet to seize control of the English Channel and provide cover for an invading army to be ferried over on barges from the Low Countries. Ships of the Spanish and Portuguese navies, as well as dozens of others that could be commandeered or hired, gathered in Lisbon and on this date the first of 130 ships set sail. Galleons, galleasses, caravels, naos, pataches, pinnaces, carracks, supply hulks and even (madness!) galleys carried 8,766 sailors, 21,556 soldiers, and 2,088 convict rowers. Over half the ships never returned home.

1905 The Battle of Tsushima A clash of two empires, one in the ascendant and the other in sharp decline. In 1904 Japan launched the Russo-Japanese War, primarily to expel Russia from the parts of China that Tokyo wanted to exploit and to prevent any further Russian expansion in east Asia. It laid siege to the Russian naval base of Port Arthur in northern China and won victories on land and sea. This compelled Russia to order its Baltic Fleet to the rescue. For the next six months the Russian armada made its sluggish way to the Sea of Japan, short on fuel and supplies, and having disgraced itself on the way by attacking a British fishing fleet in the North Sea under the impression it was a flotilla of Japanese torpedo boats.

A clash of two empires, one in the ascendant and the other in sharp decline. In 1904 Japan launched the Russo-Japanese War, primarily to expel Russia from the parts of China that Tokyo wanted to exploit and to prevent any further Russian expansion in east Asia. It laid siege to the Russian naval base of Port Arthur in northern China and won victories on land and sea. This compelled Russia to order its Baltic Fleet to the rescue. For the next six months the Russian armada made its sluggish way to the Sea of Japan, short on fuel and supplies, and having disgraced itself on the way by attacking a British fishing fleet in the North Sea under the impression it was a flotilla of Japanese torpedo boats.

By the time the Russian navy arrived, Port Arthur had fallen and the new plan of Admiral Rozhestvensky was to make his way to the port of Vladivostok where other Russian ships were waiting. Japanese Admiral Togo foresaw the Russian route; the two fleets met in the Straits of Tsushima off the coast of Korea. The Japanese gunnery and ship handling (both expertly tutored by the British Royal Navy) eviscerated the Russians — only three of their ships were able to escape to Vladivostok. Two Russian admirals were put on trial after their return home. The humiliating defeat contributed greatly to civilian unrest at home, weakening the position of the Romanov dynasty.