To show themselves obedient, came Joseph and Mary unto Bethlehem; a long journey, and poor folks, and peradventure on foot; for we read of no great horses that she had, as our great ladies have nowadays; for truly she had no such jolly gear… Well, she was great with child, and was now come to Bethlehem, where they could get never a lodging in no inn, and so were compelled to lie in a stable; and there Mary, the mother of Christ, brought forth that blessed child and there she wrapped Him in swaddling clothes and laid Him in a manger, because there was no room for them at the inn. For the innkeepers took only those who were able to pay for their good cheer; they would not meddle with such beggarly folk as Joseph and Mary his wife were.

But I warrant you there was many a jolly damsel at that time in Bethlehem, yet amongst them all there was not one found that would humble herself so much as once to go and see poor Mary in the stable, and to comfort her. No, no; they were too fine to take so much pains, I warrant you, they had bracelets and vardingales; like there be many nowadays amongst us, which study nothing else but how they may desire fine raiment; and in the mean season they suffer poor Mary to lie in the stable. ..

But what was her swaddling-clothes wherein she laid the King of heaven and earth? No doubt it was poor gear; peradventure it was her kercher which she took from her head, or such like gear; for I think Mary had not much fine linen; she was not trimmed up as our women be nowadays; for in the old time women were content with honest and single garments. Now they have found out these round-a-bouts; they were not invented then; the devil was not so cunning to make such gear, he found it out afterward. Who fetched water to made a fire? It is like that Joseph did such things; for, as wash the child after it was born into the world, and who Here is a question to be moved. told you before, those fine damsels thought it scorn to do any such thing unto Mary.

But, to whom was the Nativity of Christ first opened? To the bishops, or great lords which I pray you, were at that time at Bethlehem? Or to those jolly damsels with their vardingales, with their round-a-bouts, or with their bracelets? No, no; they had so many lets to trim and dress themselves, that they could have no time to hear of the Nativity of Christ.

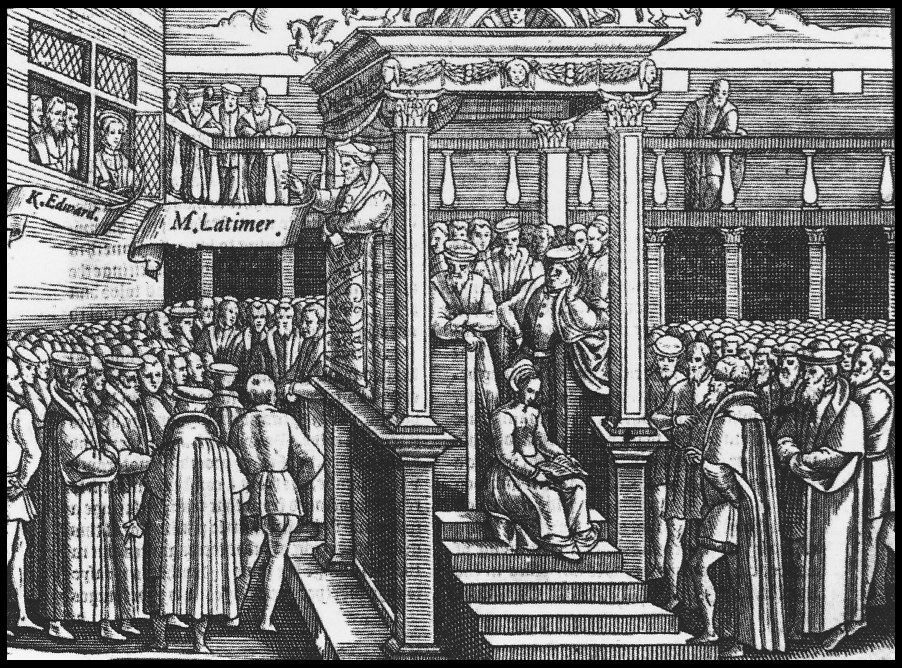

But his nativity was narrated first to the shepherds … – Hugh Latimer