1780 The Gordon Riots

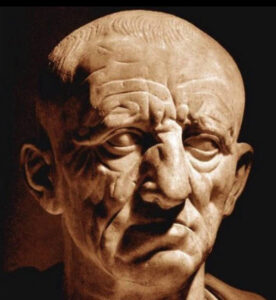

On the 7th of June in 1780, London was in the almost unchecked possession of a mob composed of the vilest of the populace, in consequence of a singular series of circumstances. A movement for tolerance to the small minority of Catholics—resulting in an act [The Papists Act,1778] for the removal of some of their disabilities in England, and the introduction of a bill (1779) for a similar measure applicable to the mere handful of that class of religionists in Scotland—had roused all the intolerant Protestant feeling in the country, and caused shameful riots in Edinburgh. A so-called Protestant Association, headed by a half-insane member of the House of Commons—Lord George Gordon [pictured below], brother of the Duke of Gordon —busied itself in the early part of 1780 to besiege the Houses of Parliament with petitions for the repeal of the one act and the prevention of the other.

On the 7th of June in 1780, London was in the almost unchecked possession of a mob composed of the vilest of the populace, in consequence of a singular series of circumstances. A movement for tolerance to the small minority of Catholics—resulting in an act [The Papists Act,1778] for the removal of some of their disabilities in England, and the introduction of a bill (1779) for a similar measure applicable to the mere handful of that class of religionists in Scotland—had roused all the intolerant Protestant feeling in the country, and caused shameful riots in Edinburgh. A so-called Protestant Association, headed by a half-insane member of the House of Commons—Lord George Gordon [pictured below], brother of the Duke of Gordon —busied itself in the early part of 1780 to besiege the Houses of Parliament with petitions for the repeal of the one act and the prevention of the other.

On the 2nd of June a prodigious Protestant meeting was held in St. George’s Fields —on a spot since, with curious retribution, occupied by a Catholic cathedral—and a ‘ monster petition,’ as it would now be called, was carried in procession through the principal streets of the city, to be laid before Parliament. Lord George had by this time, by his wild speeches, wrought up his adherents to a pitch bordering on frenzy. In the lobbies of the Houses scenes of violence occurred, resembling very much those which were a few years later exhibited at the doors of the French Convention, but without any serious consequences. The populace, however, had been thoroughly roused, and the destruction of several houses belonging to foreign Catholics was effected that night. Two days after, a Sunday, a Catholic chapel in Moorfields was sacked and burned, while the magistrates and military presented no effective resistance.

On the 2nd of June a prodigious Protestant meeting was held in St. George’s Fields —on a spot since, with curious retribution, occupied by a Catholic cathedral—and a ‘ monster petition,’ as it would now be called, was carried in procession through the principal streets of the city, to be laid before Parliament. Lord George had by this time, by his wild speeches, wrought up his adherents to a pitch bordering on frenzy. In the lobbies of the Houses scenes of violence occurred, resembling very much those which were a few years later exhibited at the doors of the French Convention, but without any serious consequences. The populace, however, had been thoroughly roused, and the destruction of several houses belonging to foreign Catholics was effected that night. Two days after, a Sunday, a Catholic chapel in Moorfields was sacked and burned, while the magistrates and military presented no effective resistance.

The consignment of a few of the rioters next day to Newgate roused the mob to a pitch of violence before unattained, and from that time till Thursday afternoon one destructive riot prevailed. On the first evening, the houses of several eminent men well affected to the Catholics and several Catholic chapels were destroyed. Next day, Tuesday, the 6th, there was scarcely a shop open in London. The streets were filled with an uncontrolled mob. The Houses of Parliament assembled with difficulty, and dispersed in terror. The middle-class inhabitants—a pacific and innocent set of people—went about in consternation, some removing their goods, some carrying away their aged and sick relations. Blue ribbons were generally mounted, to give assurance of sound Protestantism, and it was a prevalent movement to chalk up ‘NO POPERY,’ in large letters on doors.

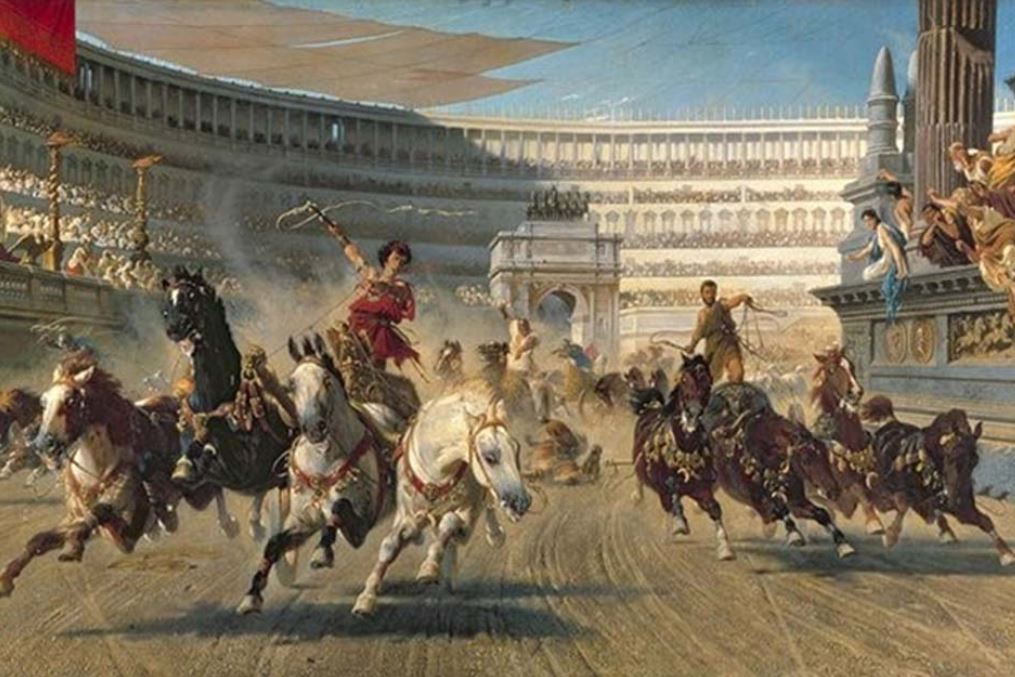

In the evening, Newgate was attacked and set fire to, and 300 prisoners let loose. The house of Lord Mansfield, at the north-east corner of Bloomsbury Square, was gutted and burnt, the justice and his lady barely making their escape by a back-door. The house and distillery of a Mr. Langdale, a Catholic, at the top of Holborn Hill, were destroyed, and there the mob got wildly drunk with spirits, which flowed along the streets like water. While they in many various places were throwing the household furniture of Catholics out upon the street, and setting fire to it in great piles, or attacking and burning the various prisons of the metropolis, there were bands of regular soldiery and militia looking on with arms in their hands, but paralysed from acting for want of authority from the magistrates. Mr. Wheatley’s famous picture, of which a copy is annexed, gives us a faint idea of’ the scenes thus presented; but the shouts of the mob, the cries of women, the ring of fore-hammers breaking open houses, the abandonment of a debased multitude lapping gin from the gutters, the many scenes of particular rapine carried on by thieves and murderers, must be left to the imagination.

Thirty-six great conflagrations raged that night in London; only at the Bank was the populace repelled—only on Blackfriars Bridge was there any firing on them by the military. Day broke upon the metropolis next day as upon a city suddenly taken possession of by a hostile and barbarous army. It was only then, and by some courage on the part of the king, that steps were taken to meet violence with appropriate measures. The troops were fully empowered to act, and in the course of Thursday they had everywhere beaten and routed the rioters, of whom 210 were killed, and 218 ascertained to be wounded. Of those subsequently tried, 59 were found guilty, and of these the number actually executed was twenty.

The leader of this strange outburst was thrown into the Tower, and tried for high treason; but a jury decided that the case did not warrant such a charge, and he was acquitted. The best condemnation that could be administered to the zealots he had led was the admission generally made of his insanity—followed up by the fact, some years later, of his wholly abandoning Christianity, and embracing Judaism. It is remarkable that Lord George’s family, all through the seventeenth century, were a constant trouble to the state from their tenacity in the Catholic faith, and only in his father’s generation had been converted to Protestantism, the agent in the case being a duchess-mother, an Englishwoman, who was rewarded for the act with a pension of £1000 a-year. Through this Duchess of Gordon, however, Lord George was great-grandson of the half-mad Charles Earl of Peterborough, and hence, probably, the maniacal conduct which cost London so much.

See https://georgiasouthern.libguides.com/c.php?g=602478&p=5463809 for an interactive map that charts the mayhem in London.