1939

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

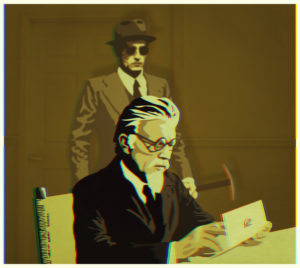

By the summer of 1939 it was clear that Adolf Hitler had no intention of keeping the peace in Europe; all of his previous promises had been broken and the German army was being put on a war footing. In order to head off more German aggression, the British and French had guaranteed their military support to Poland and sought to involve the Soviet Union in an anti-German alliance. The Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin feared the western nations as much as he did the Germans. He demanded as a price for allying against Germany the right of the Red Army to enter Poland; the Poles, quite rightly, feared that once the Russians were in their country there would be no getting them out. Stalin, therefore, entered secret negotiations with his arch-enemies in Nazi Germany and received the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop for talks with Vyacheslav Molotov, the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs. The result, which staggered the world, was the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the so-called Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

On the surface, the treaty was a pledge of neutrality should either country go to war against another country, and a ten-year pledge of peace between the signatories. It was seen, at once, as a carte blanche for Hitler to go to war against Poland, secure that the USSR would not intervene. As such, it made World War II inevitable. Around the world, it also shocked Communist supporters who had been told that Nazi German was the supreme enemy; the Soviet excuse that the two countries shared a common anti-capitalist stance was met with derision. Many western intellectuals and artists who had seen Stalin as the bulwark against fascism never got over their disillusionment and abandoned Communism; others continued to toe the Party line and to oppose war with Germany until 1941 when Hitler broke the pact and invaded the Soviet Union. The folk-singer Woodie Guthrie was in the latter camp, making a mockery of the motto on his guitar which read “This Machine Kills Fascists”.

What the world did not know in August of 1939 was that there were secret articles of the treaty that were even more sinister. In return for its acquiescence in the invasion of Poland, Germany would allow the Soviet Union to occupy Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Bessarabia and the eastern part of Poland. Once war started in September, the two tyrannies cooperated in massacres of Poles, Jews, and prisoners of war.