1662

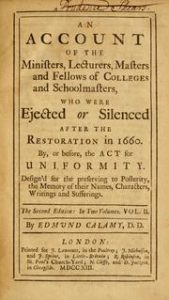

The Act of Uniformity

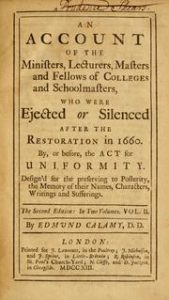

When High Church had the upper hand in the reign of Charles I, it did not hesitate to pillory the Puritans, cut off their ears, and banish them. When the Puritans got the ascendancy afterwards, they treated high-churchmen with an equally conscientious severity. At the Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660, all the reforming plans of the last twenty years were found utterly worn out of public favour, and the public submitted very quietly to a reconstitution of the church under what was called the Act of Uniformity, which made things very unpleasant once more for the Puritans. By its provisions, every clergyman was to be expelled from his charge on the 24th of August 1662, if, by that time, he did not declare his assent to everything contained in the revised Book of Common Prayer; every clergy-man who, during the period of the Commonwealth, had been unable to obtain episcopal ordination, was commanded now to obtain that kind of sanction; all were to take an oath of canonical obedience; all were to give up the theory on which the old ‘Solemn League and Covenant’ had been based; and all were to accept the doctrine of the king’s supremacy over the church. The result was, that two thousand of the clergy signalised this Bartholomew Day by leaving the church. Laymen such as John Milton, John Bunyan, and Andrew Marvell, left as well.

The act became the more harsh from its coming into operation just before one whole year’s tithes were due. Two thousand families, hitherto dependent on stipends for support, were driven hither and thither in the search for a livelihood; and this was rendered more and more difficult by a number of subordinate statutes passed in rapid succession. The ejected ministers were not allowed to exercise, even in private houses, the religious functions to which they had been accustomed. Their books could not be published without episcopal sanction, previously applied for and obtained. A statute, called the ‘Conventicle Act,’ punished with fine, imprisonment, or transportation, every one present in any private house where religious worship was carried on—if the total number exceeded by more than five the regular members of the household. Another, called the ‘Oxford Act,’ imposed on these unfortunate ministers an oath of passive obedience and non-resistance; and if they refused to take it, they were prohibited from living within five miles of any place where they had ever resided, or of any corporate town, and from eking out their scanty incomes by keeping schools, or taking in boarders. A second and stricter version of the Conventicle Act deprived the ministers of the right of trial by jury, and empowered any justice of the peace to convict them on the oath of a single informer, who was to be rewarded with one-third of the fines levied.

Writers who take opposite sides on this subject naturally differ as to the causes and justification to be assigned for the ejection; but there is very little difference of opinion as to the misery suffered during the years intervening between 1662 and 1688. Those who, in one way or other, suffered homelessness, hunger, and penury on account of the Act of Uniformity and the ejection that followed it, have been estimated at 60,000 persons, and the amount of pecuniary loss at twelve or fourteen millions sterling. Contemporary writers, record upwards of 5000 Nonconformists as the number who perished within the walls of prisons; and many, like preacher Richard Baxter, were hunted from house to house, from chapel to chapel, by informers, whose only motive was to obtain a portion of the fines levied for infringement of numerous statutes.

Considered as a historical fact, dissent may be said to have begun in England on this 24th August 1662, when the Puritans, who had before formed a body within the church, now ranged themselves as a dissenting or Nonconformist sect outside it.