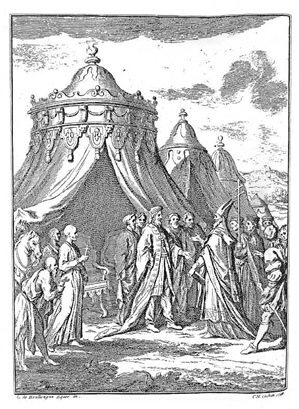

1626 Ethiopia becomes officially Roman Catholic

One of the oldest Christian churches in the world is that of Ethiopia. The country maintained its Coptic variety of Christianity over the centuries despite repeated attacks from surrounding Muslim nations. When the Portuguese reached India in the late 1400s it was possible for Roman Catholicism influence to be felt. When Ethiopia appealed for help against the Muslim Adal Sultanate in 1531, the military aid opened up the country further. Jesuit missionaries arrived and made some converts among the people but their real target was the ruling class. The Emperor Susenyos I was converted to Catholicism and in 1622 declared it to be the country’s official religion. When Afonso Mendes, a Portuguese Jesuit, was named Patriarch of the Ethiopian Church and Susenyos used force to compel the latinization, resistance grew. On the death of the Emperor the union with Rome was declared over, Mendes was expelled and the Catholic missionizing came to an official end. Jesuits who lingered were martyred.

1929 The Lateran pacts are signed

1929 The Lateran pacts are signed

The reunification of Italy in the 19th century came at the expense of the Papal States, ruled by the Pope since the 700s. When the last bit was gobbled up by Italy in 1870 subsequent popes refused to recognize the status quo and claimed to be prisoners in the Vatican. In the Lateran Pacts signed with Benito Mussolini, the fascist dictator, the Vatican received independence and reparations while agreeing to recognize the Kingdom of Italy.

2013 Pope Benedict XVI resigns the papacy

2013 Pope Benedict XVI resigns the papacy

When the noted theologian Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger was named Pope Benedict XVI in 2005 he was already 77 years old. He served as Bishop of Rome until 2013 when he stepped down from his office, not wishing to imitate the example of his predecessor John Paul II who was incapacitated in the latter part of his reign. He cited “lack of strength of mind and body” as the reason for his decision. He was the first Pope to resign since 1415 when Gregory XII was forced to step down under pressure from the Council of Constance. The last pope to resign voluntarily was the unfortunate Celestine V who retired in 1294.