The birthday of a plethora of popular culture luminaries:

1903 Bing Crosby. Harry Lillis “Bing” Crosby was more than the quintessential crooner whose career coincided with the introduction of the microphone that suited his intimate baritone. He was an Academy Award winning actor; he dominated record sales for decades; he was star on radio and television. Sadly his last public appearance was a bizarre Christmas duet with David Bowie.

1903 Bing Crosby. Harry Lillis “Bing” Crosby was more than the quintessential crooner whose career coincided with the introduction of the microphone that suited his intimate baritone. He was an Academy Award winning actor; he dominated record sales for decades; he was star on radio and television. Sadly his last public appearance was a bizarre Christmas duet with David Bowie.

1906 Mary Astor. The gorgeous Lucile Vasconcellos Langhanke was a splendid actress with a tawdry personal life. She won eternal fame for playing villainess Brigid O’Shaughnessy in The Maltese Falcon, and an Oscar for The Great Lie. Her parents were leeches and a constant source of embarrassment while Astor herself enjoyed a string of husbands and lovers. Her diary, in which she kept details of her amorous encounters, proved a scandal during one of her divorces but she died a faithful Catholic and a recovered alcoholic.

1906 Mary Astor. The gorgeous Lucile Vasconcellos Langhanke was a splendid actress with a tawdry personal life. She won eternal fame for playing villainess Brigid O’Shaughnessy in The Maltese Falcon, and an Oscar for The Great Lie. Her parents were leeches and a constant source of embarrassment while Astor herself enjoyed a string of husbands and lovers. Her diary, in which she kept details of her amorous encounters, proved a scandal during one of her divorces but she died a faithful Catholic and a recovered alcoholic.

1919 Pete Seeger. A splendid folk singer and an engaging personality, Seeger never quite shook off his association with Stalinism in the 1930s. Following the Moscow line, Seeger and his fellow American Marxists opposed any war against Hitler until mid-1941 and the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union. Seeger quit the Communist Party in 1949 but continued to have trouble with Washington who viewed his progressive politics as being subversive. He supported every conceivable left wing cause in his music, from Republican Spain, unionism, the Hollywood Ten, the Rosenbergs, the death penalty, the Vietnam War, Occupy Wall Street, Obama, and environmentalism. He professed communism until the day he died but, late in life, did express misgivings about the Gulags. I love his banjo-only versions of some traditional Christmas music.

1919 Pete Seeger. A splendid folk singer and an engaging personality, Seeger never quite shook off his association with Stalinism in the 1930s. Following the Moscow line, Seeger and his fellow American Marxists opposed any war against Hitler until mid-1941 and the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union. Seeger quit the Communist Party in 1949 but continued to have trouble with Washington who viewed his progressive politics as being subversive. He supported every conceivable left wing cause in his music, from Republican Spain, unionism, the Hollywood Ten, the Rosenbergs, the death penalty, the Vietnam War, Occupy Wall Street, Obama, and environmentalism. He professed communism until the day he died but, late in life, did express misgivings about the Gulags. I love his banjo-only versions of some traditional Christmas music.

1928 Dave Dudley. David Darwin Pedruska became a big cross-over star in 1963 with his truck-driving ballad,”Six Days on the Road”. The song set the fashion for a new genre of country music and provided a decent living for Dudley who found that his popularity lingered in Europe for decades after his star had faded at home.

1928 Dave Dudley. David Darwin Pedruska became a big cross-over star in 1963 with his truck-driving ballad,”Six Days on the Road”. The song set the fashion for a new genre of country music and provided a decent living for Dudley who found that his popularity lingered in Europe for decades after his star had faded at home.

1933 James Brown. “Mr. Dynamite.” “The Hardest Working Man in Show Business.” “The Godfather of Soul”. “Soul Brother No. 1.” No more need be said.

1933 James Brown. “Mr. Dynamite.” “The Hardest Working Man in Show Business.” “The Godfather of Soul”. “Soul Brother No. 1.” No more need be said.

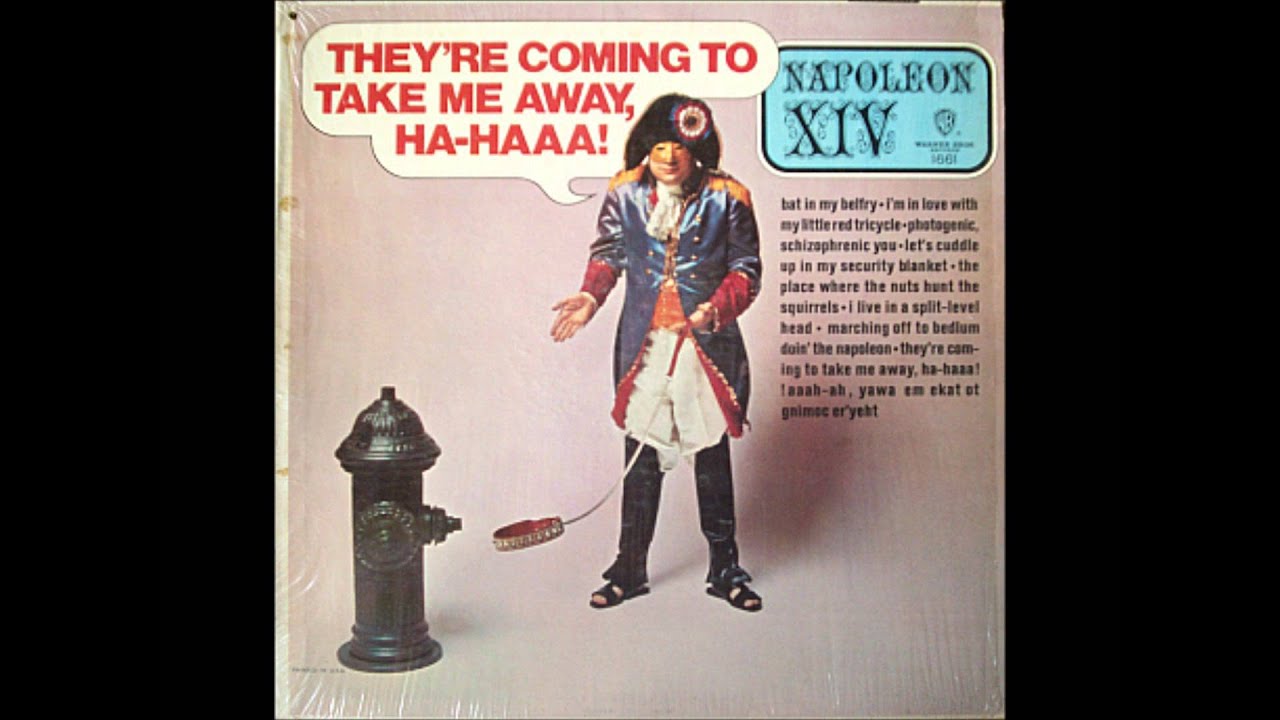

1938 Napoleon XIV. In 1966 Jerrold “Jerry” Samuels gave us the definition of a one-hit wonder and a testimony to the debased taste of a lost generation with the immortal cry of existential angst that was “They’re Coming to Take Me Away”. With great sensitivity, he further examined the hilarious side of mental illness with such other gems as “Bats in My Belfry”, “The Nuts on My Family Tree”, and “Photogenic, Schizophrenic You”.

1938 Napoleon XIV. In 1966 Jerrold “Jerry” Samuels gave us the definition of a one-hit wonder and a testimony to the debased taste of a lost generation with the immortal cry of existential angst that was “They’re Coming to Take Me Away”. With great sensitivity, he further examined the hilarious side of mental illness with such other gems as “Bats in My Belfry”, “The Nuts on My Family Tree”, and “Photogenic, Schizophrenic You”.