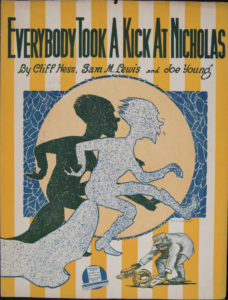

We all rightly the lament the murder of Tsar Nicholas II and his family by his Bolshevik captors in 1918 but we forget that his overthrow in February 1917 was widely hailed in the West. Here is some sheet music that celebrated the toppling of the Romanov dynasty.

Everybody Took a Kick at Nicholas

Mister Romanoff who was the Russian ruler,/Now is roamin’ off to where the weather’s cooler;

Just twinkle little Czar,/We’re glad you’re where you are.

Every gate is locked up with a big Kerens key,

He’s all alone,/Nick and his Queen, his old Czardine

Were thrown off the throne.

Everybody took a kick at Nicholas/He was kicked in the nick of time.

They took his motor car,/Drove him far,

Let him in the woods and said,/“Now there you’se are.”

Left-o-witch or Right-o-witch took all his coins away,

I really don’t know which is which but that is what they say;

That “every body took a kick at Nicholas/And Nicholas is nickeless now.”

Nick once sat upon a throne and gave out orders/Now he’s got a 12-room flat and takes in boarders;

And that Rasputin gent,/Owes Nick a whole month’s rent.

Mister Nick is married to the Kaiser’s sisters/She cooks his meals

Where sauerkraut, pushed in his mouth/Just think how poor Nick feels.

Now the Czarine says, “there’s no disputin’ why I cry,

It’s all because I miss the way Rasputin winked his eye.”

So “everybody took a kick at Nicholas/And Nicholas is nickeless now.”