1332 Birth of Ibn Khaldun

The greatest of all Muslim historiographers is Abd-ar-Rahman ibn Muhammed ibn Khaldun al Hadrani or, for short, Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406). Ibn Khaldun was born in Tunis, of an Arab family with strong ties to Muslim Spain (especially Seville) going back to the 9th century. The family had left Seville for North Africa immediately before the city’s Reconquista by Christian forces in 1288. From there they went to Ifriqiya and settled in Tunis becoming high-ranking civil servants and scholars. His great-grandfather was tortured and murdered by a usurper in the turbulent politics of the area.

The greatest of all Muslim historiographers is Abd-ar-Rahman ibn Muhammed ibn Khaldun al Hadrani or, for short, Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406). Ibn Khaldun was born in Tunis, of an Arab family with strong ties to Muslim Spain (especially Seville) going back to the 9th century. The family had left Seville for North Africa immediately before the city’s Reconquista by Christian forces in 1288. From there they went to Ifriqiya and settled in Tunis becoming high-ranking civil servants and scholars. His great-grandfather was tortured and murdered by a usurper in the turbulent politics of the area.

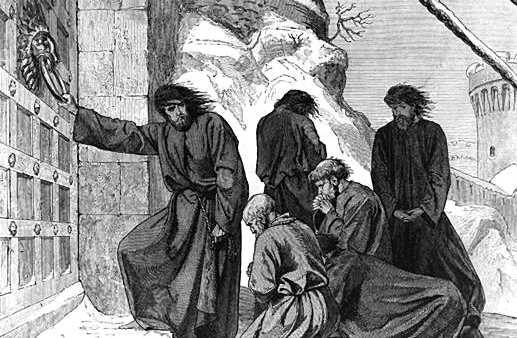

Ibn Khaldun received a very thorough education, a classical education, based on the study of the qur’an, of hadith, of the Arabic language and of Islamic law. As a teenager he survived the Black Death of 1349 and moved to Fez, then the most brilliant capital of the Muslim West. For a time he served the Sultan of Fez and then visited Spain where he was employed by the King of Granada who used him as an envoy to Pedro the Cruel of Castile. Chaotic politics saw him cast into jail for two years and serving a number of masters in Spain and North Africa. He made the pilgrimage to Mecca and saw Alexandria and Cairo where he served as Chief Justice to the Mameluke Sultan of Egypt. He went into retirement but was recalled in 1400 and sent to Damascus where he found himself inside the city as it was besieged by the Mongol conqueror Timur or Tamerlane. He was lowered from the walls in a basket to negotiate with the blood-thirsty Mongol; he impressed Timur who consulted him on historical matters and spared him when the city was taken and its inhabitants massacred. He returned to Egypt (having been stripped and robbed by bandits) and took up a position again as judge. He died in Cairo in 1406.

Ibn Khaldun began his great work of history, the Muqaddimah (Introduction) in the 1370s when he was in his late 40s and spent the rest of his life accumulating material and refining it. In the author’s intention, and as the title indicates, it is an “Introduction” to the historian’s craft. Thus it is presented as an encyclopaedic synthesis of the methodological and cultural knowledge necessary to enable the historian to produce a truly scientific work.

In his preface to the Introduction proper, Ibn khaldun begins by defining history – which he expands to include the study of the whole of the human past, including its social, economic and cultural aspects – defining its interest, denouncing the lack of curiosity and of method in his predecessors, and setting out the rules of good and sound criticism. This criticism is based essentially, apart from the examination of evidence, on the criterion of conformity with reality, that is of the probability of the facts reported and their conformity to the nature of things, which is the same as the current of history and of its evolution. Hence the necessity of bringing to light the laws which determine the direction of this current. The science capable of throwing light on this phenomenon is, he says, that of “a science which may be described as independent, which is defined by its object: human civilization and social facts as a whole”.

The central point around which his observations are built and to which his researches are directed is the study of decline, that is to say the symptoms and the nature of the ills from which civilizations die. Hence the Muqaddima is very closely linked with the political experiences of its author, who had been in fact very vividly aware that he was witnessing a tremendous change in the course of history, which is why he thought it necessary to write a summary of the past of humanity and to draw lessons from it. He remarks that at certain exceptional moments in history the upheavals are such that one has the impression of being present “at a new creation, at an actual renaissance, and at [the emergence of] a new world. It is so at present. Thus the need is felt for someone to make a record of the situation of humanity and of the world”. This “new world”‘, as Ibn Khaldun knew, was coming to birth in other lands; he also realized that the civilization to which he belonged was nearing its end. Although unable to avert the catastrophe, he was anxious at least to understand what was taking place, and therefore felt it necessary to analyse the processes of history.

His main tool in this work of analysis is observation. Ibn Khaldun had a thorough knowledge of logic and made use of it, particular of induction, but he greatly mistrusted speculative reasoning. He admits that reason is a marvellous tool, but only within the framework of its natural limits, which are those of the investigation and the interpretation of what is real. He was much concerned about the problem of knowledge and it led him finally, after a radical criticism, to a refutation of philosophy, casting doubts on the adequacy of universal rationality and of individual reality, on the whole structure of speculative philosophy as it then existed. Having thus calmly dismissed Arabo-Muslim philosophy, he chose, in order to explore reality and arrive at its meaning, a type of empiricism which has no hesitation in “having recourse to the categories of rational explanation which derive from philosophy”. In short, Ibn Khaldun rejects the traditional speculation of the philosophers, which gets bogged down in fruitless argument and controversy, only to replace it by another type of speculation, the steps of which are more certain and the results more fruitful since it is directly related to concrete facts.