In 1162 Henry II sought to bring the English Church under strict royal control by appointing to the archbishopric of Canterbury his chancellor and good friend, Thomas Becket. But in raising Becket to the primacy, Henry had misjudged his man. As chancellor, Becket had been a devoted royal servant, but as archbishop of Canterbury he became a fervent defender of ecclesiastical independence and an implacable enemy of the king. Henry and Becket became locked in a furious quarrel over the issue of royal control of the English Church. In 1164 Henry issued a list of pro-royal provisions relating to Church-state relations known as the “Constitutions of Clarendon,” which, among other things, prohibited appeals to Rome without royal license and established a degree of royal control over the Church courts. Henry maintained that the Constitutions of Clarendon represented ancient custom; Becket regarded them as unacceptable infringements of the freedom of the Church.

At the heart of the quarrel was the issue of whether churchmen accused of crimes should be subject to royal jurisdiction after being found guilty and punished by Church courts. The king complained that “criminous clerks” were often given absurdly light sentences by the ecclesiastical tribunals. A murderer, for example, might simply be banished from the priesthood (“defrocked”) and released, whereas in the royal courts the penalty was execution or mutilation. The Constitutions of Clarendon provided that once a cleric was tried, convicted, and defrocked by an ecclesiastical court, the Church should no longer prevent his being brought to a royal court for further punishment. Becket replied that nobody ought to be put in double jeopardy. In essence, Henry was challenging the competence of an agency of the international Church, whereas Becket, as primate of England, felt bound to defend the ecclesiastical system of justice and the privileges of churchmen. Two worlds were in collision.

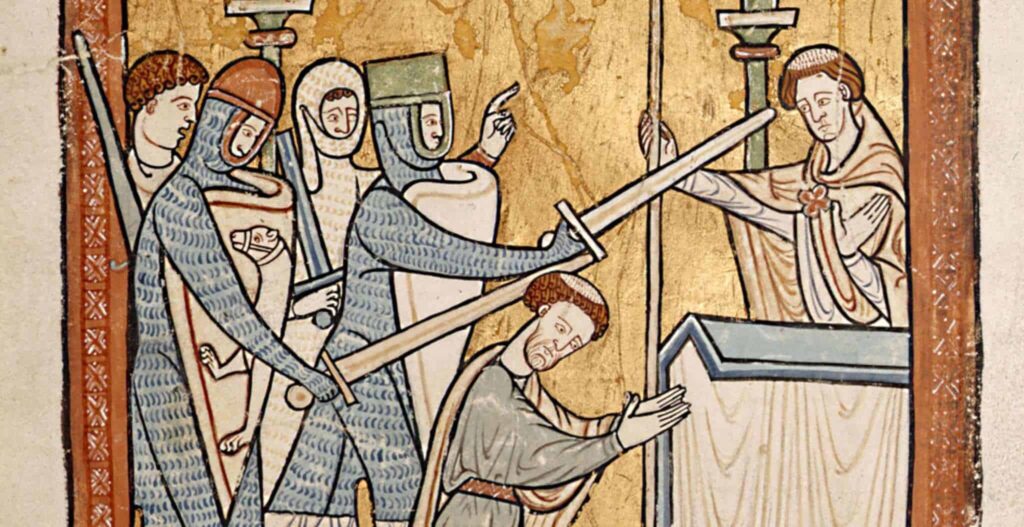

Henry turned on his archbishop, accusing him of various crimes against the kingdom. And Becket, insisting that an archbishop cannot be judged by a king but only by the pope, fled England to seek papal support. Pope Alexander III, who was in the midst of his struggle with Frederick Barbarossa, could not afford to alienate Henry; yet neither could he turn against such an ardent ecclesiastical champion as Becket. The great lawyer-pope was forced to equivocate—to encourage Becket without breaking with Henry—and Becket remained in exile for the next six years. At length, in 1170, the king and his archbishop agreed to a truce. Most of the outstanding issues between them remained unsettled, but Henry permitted Becket to return to England and resume the archbishopric. At once, however, the two antagonists had another falling out. Becket excommunicated a number of Henry’s supporters; the king flew into a rage, and four enthusiastically loyal but dim-witted barons of the royal household dashed to Canterbury Cathedral, intimidated Becket and his monks, and then murdered him as he was saying Mass.

This dramatic atrocity made a deep impact on the age. Becket was regarded as a martyr; miracles were alleged to have occurred at his tomb, and he was quickly canonized. For the remainder of the Middle Ages, Canterbury was a major pilgrimage center, and the cult of St. Thomas enjoyed immense popularity. Henry, who had not ordered the killing but whose anger had prompted it, suffered acute embarrassment. He was obliged to do penance by walking barefoot through the streets of Canterbury and submitting to a flogging by the Canterbury monks (who seem to have enjoyed the episode immensely).