In 1879 Catholicism began spreading in Uganda when the White Fathers, a congregation of priests founded by Cardinal Lavigerie were peacefully received by King Mutesa of Uganda. The priests soon began preparing catechumens for baptism and before long a number of the young pages in the king’s court had become Catholics.

However, on the death of Mutesa, his son Mwanga, a corrupt man who ritually engaged in pedophilic practices with the younger pages, took the throne. When King Mwanga had a visiting Anglican Bishop murdered, his chief page, Joseph Mukasa, a Catholic who went to great length to protect the younger boys from the king’s lust, denounced the king’s actions and was beheaded on November 15, 1885.

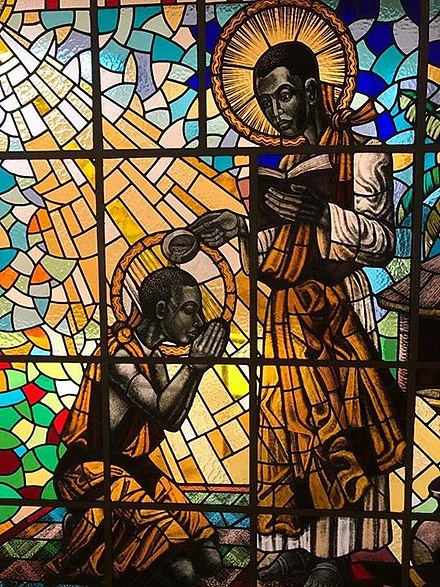

The 25 year old Charles Lwanga, a man wholly dedicated to the Christian instruction of the younger boys, became the chief page, and just as forcibly protected them from the kings advances. On the night of the martyrdom of Joseph Mukasa, realizing that their own lives were in danger, Lwanga and some of the other pages went to the White Fathers to receive baptism. Another 100 catechumens were baptized in the week following Joseph Mukasa’s death.

The following May, King Mwanga learned that one of the boys was learning catechism. He was furious and ordered all the pages to be questioned to separate the Christians from the others. The Christians, 15 in all, between the ages of 13 and 25, stepped forward. The King asked them if they were willing to keep their faith. They answered in unison, “Until death!”

They were bound together and taken on a two day walk to Namugongo where they were to be burned at the stake. On the way, Matthias Kalemba, one of the eldest boys, exclaimed, “God will rescue me. But you will not see how he does it, because he will take my soul and leave you only my body.” They executioners cut him to pieces and left him to die alone on the road. When they reached the site where they were to be burned, they were kept tied together for seven days while the executioners prepared the wood for the fire.

On June 3, 1886, the Feast of the Ascension, Charles Lwanga was separated from the others and burned at the stake. The executioners slowly burnt his feet until only the charred remained. Still alive, they promised him that they would let him go if he renounced his faith. He refused saying, “You are burning me, but it is as if you are pouring water over my body.” He then continued to pray silently as they set him on fire. Just before the flames reached his heart, he looked up and said in a loud voice, “Katonda! – My God!,” and died. His companions, some Catholic, some Anglican, were all burned together the same day all the while praying and singing hymns until they died.