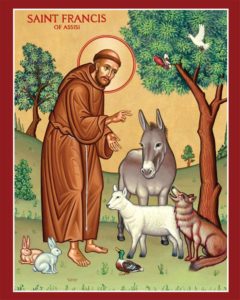

October 4 is the feat of St Francis of Assisi, the namesake of the current pope. Chamber’s Book of Days has this to say about him:

The memory of no saint is held in affection so mingled with reverence by the Roman Catholic Church as St. Francis, ‘the gentle and the holy.’ He was born in 1182, in the romantic town of Assisi, in Umbria. His father was a merchant, and a hard money-making man. Francis he took into partnership, but he wasted his money in gay living, splendid dress, and banqueting, and made the streets of Assisi ring at night with song and frolic. When about twenty-five, he was seized with a violent illness, and when he rose from his bed, nature looked dreary, and his soul was filled with loathing for his past life and habits. He resolved to he religious, and of course religious after the fashion of his generation. He determined never to refuse alms to a poor person. He met a troop of beggars, and exchanged his dress for the rags of the filthiest. He mortified himself with such severity, that Assisi thought he had gone distracted. His father had been distressed by his luxury, but now he thought he should be ruined by his alms-giving. To bring him, as he thought, to his senses, he beat him unmercifully, put him in fetters, and locked him up. Finding him, however, incorrigible, he carried him before the bishop; and there and then he renounced all his rights of ownership and inheritance, and stripped off’ his clothes in token of his rejection of the world, and his perpetual choice of poverty.

Francis, thus relieved from all entanglement, pursued his way with. a simple energy which nothing could withstand. The fervour of his devotion diffused itself like an epidemic, and crowds parted with their possessions, and followed him into poverty and beggary. He went to Rome, and offered himself and his comrades to the service of the pope Innocent III, in 1210, incorporated the order, which grew into the mighty and wide-spread fraternity of Franciscans, Grey Friars, or Minor Friars. The first name they had from their founder, the second from their gray clothing, and the third from their humility. Their habit was a loose garment, of a gray color reaching to the ankles, with a cowl of the same, and a cloak over it when they went abroad. They girded themselves with cords, and went barefooted.

The austerities related of Francis are very much of a piece with those told of other saints. He scarcely allowed his body what was necessary to sustain life. If any part of his rough habit seemed too soft, he darned it with packthread, and was wont to say to his brethren, that the devils easily tempted those who wore soft garments. His bed was usually the ground, or he slept sitting, and for his bolster he had a piece of wood or stone. Unless when sick, he rarely ate any food that was cooked with fire, and when he did, he sprinkled it with ashes. Yet it is said, that with indiscreet or excessive austerity he was always displeased. When a brother, by long fasting, was unable to sleep, Francis brought him some bread, and persuaded him to eat by eating with him. In treating with women, he kept so strict a watch over his eyes, that he hardly knew any woman by sight. He used to say:

‘To converse with women, and not be hurt by it, is as difficult as to take fire into one’s bosom and not be burned. He that thinks himself secure, is undone; the devil finding somewhat to take hold on, though it be but a hair, raises a dreadful war.’

He was endowed, say his biographers, with an extraordinary gift of tears; his eyes were as fountains which flowed continuously, and by much weeping he almost lost his sight. In his ecstatic raptures, he often poured forth his soul in verse, and Francis in among the oldest vernacular poets of Italy. His sympathy with nature was very keen. He spoke of birds and beasts with all the tenderness due to children, and Dean Milman says the only malediction he can find which proceeded from his lips, was against a fierce swine which had killed a lamb. He had an especial fondness for lambs and larks, as emblems of the Redeemer and the Cherubim. When his surgeon was about to cauterize him for an issue, he said: ‘Fire, my brother, be thou discreet and gentle to me.’ In one of his hymns, he speaks of his brother the Sun, his sister the Moon, his brother the Wind, his sister the Water. When dying, he said:

‘Welcome, Sister Death.’ While in prayer it is said that he often floated in the air. Leo, his secretary and confessor, testified that he had seen him, when absorbed in devotion, raised above the ground so high that he could only touch his feet, which he held, and watered with his tears; and that some-times he saw him raised much higher!

In his ardor for the conversion of souls, he set out to preach to the Mohammedans. A Christian army was encamped before Damietta, in Egypt. He passed beyond its lines and was seized and carried before the sultan, and at once broke forth in exposition of the mysteries of faith. The sultan is reported to have listened with attention, probably with the Mohammedan reverence for the insane. Francis offered to enter a great fire with the priests of Islam, and to test the truth of their creeds by the result. The offer was declined. ‘I will then enter alone,’ said Francis. If I should be burned, you will impute it to my sins; should I come forth alive, you will embrace the gospel.’ This also the sultan refused, but with every mark of honour convoyed the bold apostle to the camp at Damietta.

The crowning glory of the life of Francis is reputed to have occurred in the solitude of Mount Alverno, whither he had retired to hold a solemn fast in honour of the archangel Michael. One morning, when he was praying, he saw in vision a seraph with six wings, and in the midst of the wings the crucified Saviour. As the vision disappeared, and left on his mind an unutterable sense of delight and awe, he found on his hands and feet black excrescences like nails, and in his side a wound, from which blood frequently oozed, and stained his garment. These marks, in his humility, he hid with jealous care, but they became known, and by their means were wrought many miracles. Pope Alexander IV publicly declared that, with his own eyes, he had seen the stigmata.