1294

The election of a dreadful pope

Benedetto Caetani (1230-1303) was an ambitious Italian churchman, serving the papacy as a diplomat, lawyer and cardinal. In 1294 he convinced the unworldly (or perhaps simple-minded) Pope Celestine V to resign and was elected pope in his place, taking the name Boniface VIII. Celestine was arrested and soon died in jail. At his coronation two kings led the pope’s horse and later served him at the banquet – symbolic to Boniface of papal superiority over mere monarchs. His reign was marked by quarrels with political leaders in Italy and with cardinals who opposed his election – he excommunicated some of them and ordered their home town burnt down and the land sown with salt.. He interfered in the politics of Scotland, Germany and Hungary and excommunicated the King of Denmark. But Boniface’s biggest fight would come in his struggle with England and France.

One of the most jealously guarded privileges of the medieval church was its claim to be exempt from local taxation. This claim always infuriated kings and other secular rulers — the church was by far the biggest landowner in most countries and always one of the wealthiest components in the economy, why should it not pay its fair share of taxes? Because, said the church, we are doing God’s work: we are the ones running the schools and the welfare system; we operate the orphanages and hospitals and leper asylums; we ransom Christian prisoners from the Muslims. The more money kings take from us in taxes is that much less money for the poor.

In the 1290s both the kings of England and France began to tax the holdings of the church in their countries. They were at war with each other, always an expensive business, and both were running larger bureaucracies and court systems than their predecessors, so the need of these nations for cash was greater than ever.

In 1294, Edward I sequestered all moneys found in the treasuries of all churches and monasteries. Soon he bullied the English clergy into giving him one half their incomes. In the following year he called for a third or a fourth, but they refused to pay more than a tenth. When, at the 1296 Convocation of Canterbury the king demanded a fifth of their income, the archbishop, Robert of Winchelsea, in keeping with the new legislation of Boniface, offered to consult the pope, whereupon the king outlawed the clergy, and seized all their property. In France Philip IV seized money set aside by the church for a crusade and instead used it to make war on English holdings in southern France.

Boniface replied in 1296 with a papal bull Clericis laicos which restated the immunity of the church from unwilling taxation (the church often paid “voluntary” donations when under real pressure — in France for example it was customary for the pope to agree to a 10% tax on church income to go to the king) and the automatic excommunication of anyone who tried to enforce it.

Like Edward I, Philip the Fair was constantly in need of money for his wars. And he was prepared to raise it by almost any means. In 1306 he arrested all the Jews in his dominions, and after seizing their property and loan accounts, he had them expelled from France. Edward I had treated English Jews in the same cruel fashion and for similar reasons. Philip likewise despoiled his Lombard bankers. Another of his targets was the rich crusading order of Knights Templars, from whom he had been borrowing heavily. He darkened their reputation by a campaign of malicious propaganda, much of which he may actually have believed. His charge that the Templars venerated the devil was repeated by Edward II of England, and even by the papacy. Philip had more than fifty Templars burned at the stake as heretics, and some of their wealth trickled into the royal treasury – though the papacy was able to keep Philip from most of it and diverted it to the Hospitallers. He launched a similar propaganda campaign, as we will see, against Pope Boniface VIII.

When Boniface issued Clericis laicos, Philip replied by forbidding the export of any money outside the country — if Philip couldn’t get any money out of the French church the pope wasn’t going to be able to either. Philip continued to tax his clergy. At the same time he set his agents to work spreading scandalous rumors about the pope’s morals and exerted financial pressure on Rome by cutting off all papal taxes from the French realm, forcing Boniface to submit for the moment. But a vast influx of pilgrims into Rome in the Jubilee Year of 1300 restored the pope’s confidence. He warned Philip in 1301 that the pope was the Vicar of Christ, who is placed over kings and kingdoms . He is the keeper of the keys, the judge of the living and the dead, and sits on the throne of justice, with power to extirpate all iniquity. He is the head of the Church, which is one and stainless, and not a many-headed monster, and has full Divine authority to pluck out and tear down, to build up and plant. Let not the king imagine that he has no superior, and is not subject to the highest authority in the Church. The French took this as a threat that the pope might depose Philip and throw the French throne open to someone else – an established right of the pope in the Middle Ages – and they cranked up a vicious campaign against Boniface including circulating forged documents.

He withdrew his concession to Philip the Fair on clerical taxation and in 1302 issued the bull Unam Sanctam, which asserted the doctrine of papal monarchy in uncompromising terms in 5 elements: (1) There is but one true Church, outside of which there is no salvation; but one body of Christ with one head and not two. (2) That head is Christ and His representative, the Roman pope; whoever refuses the pastoral care of Peter belongs not to the flock of Christ. (3) There are two swords (i.e., powers), the spiritual and the temporal; the first borne by the Church, the second for the Church; the first by the hand of the priest, the second by that of the king, but under the direction of the priest (ad nutum et patientiam sacerdotis). (4) Since there must be a co-ordination of members from the lowest to the highest, it follows that the spiritual power is above the temporal and has the right to instruct (or establish–instituere) the latter regarding its highest end and to judge it when it does evil; whoever resists the highest power ordained of God resists God himself. (5) It is necessary for salvation that all men should be subject to the Roman Pontiff. No pope had ever before enunciated such claims to power.

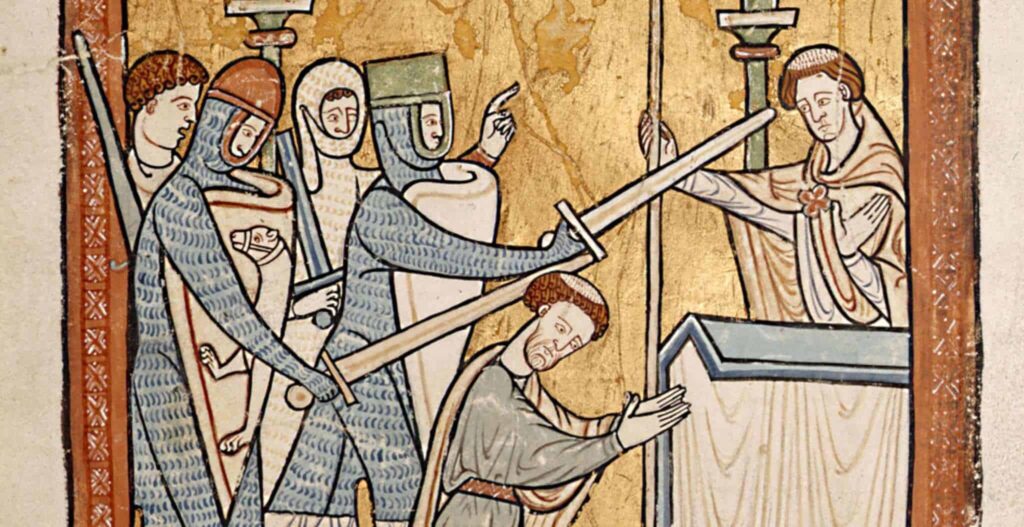

Philip the Fair now summoned a kingdom-wide assembly, and before it he accused Boniface of every imaginable crime from murder to black magic to sodomy to keeping a demon as a pet. A small French military force crossed into Italy in 1303 and took Boniface prisoner at his palace at Anagni with the intention of bringing him to France for trial. Anagni, symbolized the humiliation of the medieval papacy. The French plan failed—local townspeople freed Boniface a couple of days later—but the proud old pope died shortly thereafter, outraged and chagrined that armed Frenchmen had dared to lay hands on his sacred person. (His assault is pictured above). Contemporaries found it significant that his burial was cut short by a furious electrical storm.

In Dante’s Inferno Boniface VIII is found in the circle of Hell reserved for the punishment of the financially corrupt.