“Freddie experienced the sort of abysmal soul-sadness which afflicts one of Tolstoy’s Russian peasants when, after putting in a heavy day’s work strangling his father, beating his wife, and dropping the baby into the city’s reservoir, he turns to the cupboards, only to find the vodka bottle empty.”

Wodehouse 1

This month will mark the 106th anniversary of the publication of P.G. Wodehouse’s first humorous piece. In honour thereof, we shall post a Wodehousean flash of wit every day throughout November. Behold the first:

“There is only one cure for grey hair. It was invented by a Frenchman. It is called the guillotine.”

On the necessity of forgiveness

Of him that hopes to be forgiven it is indispensably required that he forgive. It is therefore superfluous to urge any other motive. On this great duty eternity is suspended, and to him that refuses to practise it the throne of mercy is inaccessible, and the Saviour of the world has been born in vain.

— Samuel Johnson

O tempores, o mores

We make men without chests and expect from them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honour and are shocked to find traitors in our midst.

— C.S. Lewis

A word for the depressed

“Money lost, little lost; honor lost, much lost; pluck lost, all lost”

— E.W. Hornung

As the American election nears

A general Dissolution of Principles & Manners will more surely overthrow the Liberties of America than the whole Force of the Common Enemy. While the People are virtuous they cannot be subdued; but when once they lose their Virtue they will be ready to surrender their Liberties to the first external or internal Invader. How necessary then is it for those who are determin’d to transmit the Blessings of Liberty as a fair Inheritance to Posterity, to associate on publick Principles in Support of publick Virtue.

— Samuel Adams

October 27

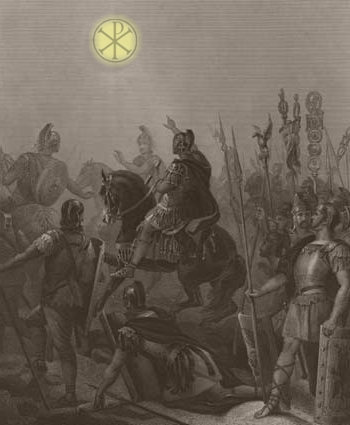

312 Constantine has a vision

The chaos in Roman politics that weakened the empire in the 3rd century was ended by reforms put in place by Diocletian (r. 284-305), particularly his institution of the Tetrarchy. Henceforth there would be four emperors: a senior Augustus in the East and in the West, each with a junior Caesar. There would be four capitals, each close to strategic border areas to allow rapid response to barbarian incursion. The plan was that when the senior rulers stepped down they would be replaced by their Caesars and the usual unseemly battles for power would be avoided. Alas, the scheme did not work in practice. After the retirement of Diocletian in 305, fighting broke out in the western part of the empire between rival generals who each thought they should be next in line. In the fall of 312, Constantine brought his army into Italy to contest the throne with Maxentius; they would meet outside Rome at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge.

According to Lactantius, on the evening of October 27 Constantine saw a vision:

Constantine was directed in a dream to cause the heavenly sign to be delineated on the shields of his soldiers, and so to proceed to battle. He did as he had been commanded, and he marked on their shields the letter Χ, with a perpendicular line drawn through it and turned round thus at the top, being the cipher of CHRIST. Having this sign (ΧР ), his troops stood to arms. The enemies advanced, but without their emperor, and they crossed the bridge. The armies met, and fought with the utmost exertions of valour, and firmly maintained their ground. In the meantime a sedition arose at Rome, and Maxentius was reviled as one who had abandoned all concern for the safety of the commonweal; and suddenly, while he exhibited the Circensian games on the anniversary of his reign, the people cried with one voice, “Constantine cannot be overcome!”

Dismayed at this, Maxentius burst from the assembly, and having called some senators together, ordered the Sibylline books to be searched. In them it was found that:— “On the same day the enemy of the Romans should perish.”

Led by this response to the hopes of victory, he went to the field. The bridge in his rear was broken down. At sight of that the battle grew hotter. The hand of the Lord prevailed, and the forces of Maxentius were routed. He fled towards the broken bridge; but the multitude pressing on him, he was driven headlong into the Tiber. This destructive war being ended, Constantine was acknowledged as emperor, with great rejoicings, by the senate and people of Rome.

Eusebius has another, more detailed account of the vision, which in his version seems to have taken place somewhat earlier. There is no doubt, however, that the triumph of Constantine led to the legal recognition of Christianity and its eventual conversion of the Roman Empire.

Something to chew on

Shakespeare is right when his Hamlet corrects Horatio’s skepticism of ghosts by telling him that “there are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamed of in your philosophy.”

That famous saying of Hamlet’s is the simplest way I know to define the difference between “post-modernism,” “modernism,” and “pre-modernism”. Pre-modernism, or traditionalism, agrees with Hamlet. There are more things in objective reality than in our minds and dreams and sciences and philosophies. Modernism, or rationalism, says there are not more things but the same number of things in those two places, in other words that we can know it all. Post-modernism says there are fewer things in objective reality than in our minds; that most of our thoughts are only dreams, prejudices, illusions, or projections.

I am neither a modernist nor a post-modernist but a pre-modernist. That’s why I habitually feel like a little kid living in a big house full of endless surprises, nooks and crannies. (I’m only 73 and I still don’t know what I want to be when I grow up.) I find the real world wonderful rather than ugly, fascinating rather than boring, mysterious rather than predictable, something that invites wonder, exploration, hope, fear, and innocence rather than cynicism, ironic distancing, and what the philosophers call a ‘hermeneutic of suspicion.’

— Peter Kreeft

And he’s right, you know

If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?

During the life of any heart this line keeps changing place; sometimes it is squeezed one way by exuberant evil and sometimes it shifts to allow enough space for good to flourish. One and the same human being is, at various ages, under various circumstances, a totally different human being. At times he is close to being a devil, at times to sainthood. But his name doesn’t change, and to that name we ascribe the whole lot, good and evil.

Socrates taught us: Know thyself!

— Alexander Solzhenitsyn

October 25

1938 An archbishop denounces “swing music”

1938 An archbishop denounces “swing music”

Churches have always been ambivalent about dance music, some clergy fearing it is the devil’s tool, an incitement to lascivious behaviour; some have made use of dance music in liturgy and in Christmas carols. The waltz, where a man and a woman hold each other in their arms and sway rhythmically, was denounced in the 19th century. The bishop of Santa Fe condemned dances as “conducive to evil, occasions of sin, [providing] opportunities for illicit affinities and love that was reprehensible and sinful.” In 1938, Francis Beckman, the Catholic Archbishop of Dubuque campaigned against “swing music”.

Beckman (1875-1948) was no stranger to controversy. He was an isolationist in foreign policy and a supporter of the radical priest Father Charles Coughlin whose radio broadcasts beamed antisemitic messages to millions in Depression-era America. He believed that calls for the USA to oppose Hitler were a communist plot. In October 1938, in a speech to the National Council of Catholic Women, he launched a crusade against contemporary dance music which he termed “a degenerated musical system… turned loose to gnaw away the moral fiber of young people”. “Jam sessions, jitterbugs and cannibalistic rhythmic orgies occupy a place in our social scheme of things,” said the archbishop, “wooing our youth along the primrose path to Hell!” He went on to say that though the Church was zealously trying to promote and preserve the best of modern art, swing music was among “the evil forces … hard at work to undermine its Christian status, debauch its high purposes and harness it to serve individual diabolical ends.”

Archbishop Beckman’s career was curtailed during the Second World War when it was discovered that he had borrowed money in his diocese’s name to invest in a shady gold mine scheme. He was allowed to retain his post but all decisions were left in the hands of a coadjutor bishop.