Here is a jolly Canadian image from the First World War with Santa as an army officer.

It is common during wartime to use Christmas as a psychological ploy against one’s enemies, usually by encouraging opposition soldiers to desert or weaken their resolve. Here is one used by Communist forces during the Korean War. Inside was a letter telling American and Allied troops that this was an unjust war.

Here is an extremely rare card from the Spanish Civil War in 1937. Inside it reads:

With the Season’s Greetings

Christmas… 1937

New Year… 1938

From the Volunteers of the 15th International Brigade and Their Brothers in the Spanish Republican Army

British Battalion • Lincoln-Washington Battalion • Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion • And Spanish Volunteers.

The Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion (the “Mac-Paps”) were the Canadian volunteers who fought against Franco’s forces on behalf of the Spanish Republic.

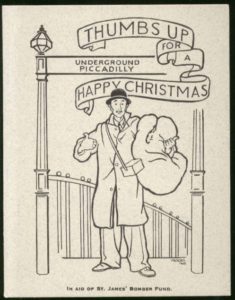

A plucky British card from 1940. The undaunted middle-class gent prepares to spend the night in the Tube station with his gas mask and blanket.

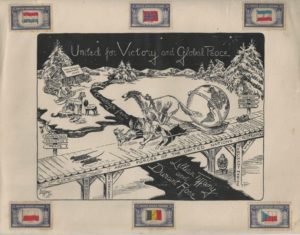

Here is a very curious American card from 1943 produced by someone who obviously loved dogs. The borzoi of Russia, the Pekinese of China, the British bulldog and the American boxer pull the sled of unity toward world peace.