1164

The death of Héloïse

Chambers recounts the story of Peter Abélard (1079-1142), a brilliant but erratic theologian, and Héloïse, a scholar and nun (1090-1164). Abélard was a remarkable philosopher but not a good man, as you shall learn:

The story of Heloise and Abelard is one of the saddest on record. It is a true story of man’s selfishness and woman’s devotion and self-abnegation. If we wished for an allegory which should be useful to exhibit the bitter strife which has to be waged between the earthly and the heavenly, between passion and principle, in the noblest minds, we should find it provided for us in this painful history. We know all the particulars, for Abelard has written his own confessions, without screening himself or concealing his guilt; and several letters which passed between the lovers after they were separated, and devoted to the exclusive service of religion, have come down to posterity.

Not alone the tragic fate of the offenders, but also their exalted worth and distinguished position, helped to make notorious the tale of their fall. Heloise was an orphan girl, eighteen years old, residing with a canon of Notre Dame, at Paris, who was her uncle and guardian. This uncle took great pains to educate her, and obtained for her the advantage of Abelard’s instruction, who directed her studies at first by letters. Her devotion to study rendered her remarkable among the ladies of Paris, even more than her beauty. ‘In face,’ Abelard himself informs us, ‘she was not insignificant; in her abundance of learning she was unparalleled; and because this gift is rare in women, so much the more did it make this girl illustrious through the whole kingdom.’

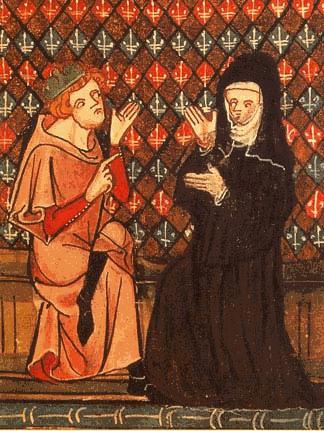

Abelard, though twice the age of Heloise, was a man of great personal attraction, as well as the most famous man of his time, as a rising teacher, philosopher, and divine. His fame was then at its highest. Pupils came to him by thousands. He was lifted up to that dangerous height of intellectual arrogance, from which the scholar has often to be hurled with violence by a hard but kind fate, that he may not let slip the true humility of wisdom. ‘Where was found,’ Heloise writes, ‘the king or the philosopher that had emulated your reputation? Was there a village, a city, a kingdom, that did not ardently wish to see you? When you appeared in public, who did not run to behold you? And when you withdrew, every neck was stretched, every eye sprang forward to follow you. The women, married and unmarried, when Abelard was away, longed for his return!’ And, becoming more explicit, she continues: ‘You possessed, indeed, two qualifications—a tone of voice, and a grace in singing—which gave you the control over every female heart. These powers were peculiarly yours, for I do not know that they ever fell to the share of any other philosopher. To soften by playful instruments the stern labours of philosophy, you composed several sonnets on love, and on similar subjects. These you were often heard to sing, when the harmony of your voice gave new charms to the expression. In all circles nothing was talked of but Abelard; even the most ignorant, who could not judge of harmony, were enchanted by the melody of your voice. Female hearts were unable to resist the impression.’ So the girl’s fancies come back to the woman, and it must have caused a pang in the fallen scholar to see how much his guilt had been greater than hers.

It was a very thoughtless thing for Fulbert to throw together a woman so enthusiastic and a man so dangerously attractive. In his eagerness that his niece’s studies should advance as rapidly as possible, he forgot the tendency of human instinct to assert its power over minds the most cultivated, and took Abelard into his house. A passionate attachment grew up between teacher and pupil: reverence for the teacher on the one hand, interest in the pupil on the other, changed into warmer emotions. Evil followed. What to lower natures would have seemed of little moment, brought to them a life of suffering and repentance. In his penitent confessions, no doubt conscientiously enough, Abelard represents his own conduct as a deliberate scheme of a depraved will to accomplish a wicked design; and such a terrible phase of an intellectual mind is real, but the circumstances in which the lovers were placed are enough to account for the unhappy issue. The world, however, it appears, was pleased to put the worst construction upon what it heard, and even Heloise herself expresses a painful doubt, long afterwards, for a moment, at a time when Abelard seemed to have forgotten her. ‘Account,’ she says, ‘for this conduct, if you can, or must I tell you my suspicions, which are also the general suspicions of the world? It was passion, Abelard, and not friendship, that drew you to me; it was not love, but a baser feeling.’

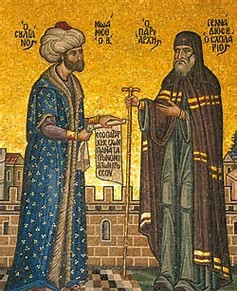

The attachment of the lovers had long been publicly known, and made famous by the songs which Abelard himself penned, to the utter neglect of his lectures and his pupils, when the utmost extent of the mischief became clear at last to the unsuspicious Fulbert. Abelard contrived to convey Heloise to the nunnery of Argenteuil. The uncle demanded that a marriage should immediately take place; and to this Abelard agreed, though he knew that his prospects of advancement would be ruined, if the marriage was made public. Heloise, on this very account, opposed the marriage; and, even after it had taken place, would not confess the truth. Fulbert at once divulged the whole, and Abelard’s worldly prospects were for ever blasted. Not satisfied with this, Fulbert took a most cruel and unnatural revenge upon Abelard, [his men castrated Abelard] the shame of which decided the wretched man to bury himself as a monk in the Abbey of St. Dennis. Out of jealousy and distrust, he requested Heloise to take the veil; and having no wish except to please her husband, she immediately complied, in spite of the opposition of her friends.

Thus, to atone for the error of the past, both devoted themselves wholly to a religious life, and succeeded in adorning it with their piety and many virtues. Abelard underwent many sufferings and persecutions. Heloise first became prioress of Argenteuil; afterwards, she removed with her nuns to the Paraclete, an asylum which Abelard had built and then abandoned. But she never subdued her woman’s devotion for Abelard. While abbess of the Paraclete, Heloise revealed the undercurrent of earthly passion which flowed beneath the even piety of the bride of heaven, in a letter which she wrote to Abelard, on the occasion of an account of his sufferings, written by himself to a friend, falling into her hands. In a series of letters which passed between them at this time, she exhibits a pious and Christian endeavour to perform her duties as an abbess, but persists in retaining the devoted attachment of a wife for her husband. Abelard, somewhat coldly, endeavours to direct her mind entirely to heaven; rather affects to treat her as a daughter than a wife; and seems anxious to check those feelings towards himself which he judged it better for the abbess of the Paraclete to discourage than to foster. Heloise survived Abelard by twenty-one years.