1794

The revolution eats its own children

It is an immutable law that revolutions are never carried out by a single group, but by a collection of various factions, each with a different goal other than simply overthrowing the existing order. It is also inevitable that revolutions become increasingly more radical, and, as they do so, they consume not just defenders of the old regime but also many of those who took a rebellious part in earlier stages of the struggle. Moderates find themselves targeted as enemies of the revolution and are repressed or killed. This radicalization will continue until eventually it becomes too oppressive and is brought to an end, exterminating the extremists, and taking a step backward.

So it was with the French Revolution. It began in the spring of 1789 with an alliance of middle-class reformers, working-class mobs, intellectuals, lawyers, and progressive clergy and nobles. Before the end of the year it had ended feudalism and aristocratic privilege, achieved a constitutional monarchy, and tamed the Catholic Church. This was not enough for many revolutionaries, however. By 1792 it had abolished the monarchy and created a republic; it had executed the royal family; it had turned anti-religious and explicitly anti-Christian; thousands of refugees had fled to Britain and neighbouring countries on the Continent. By 1793, France was at war with European monarchies as its leaders turned to Terror as an instrument of state policy.

In the words of Maximilien Robespierre, a leading Jacobin radical:

If virtue be the spring of a popular government in times of peace, the spring of that government during a revolution is virtue combined with terror: virtue, without which terror is destructive; terror, without which virtue is impotent. Terror is only justice prompt, severe and inflexible; it is then an emanation of virtue; it is less a distinct principle than a natural consequence of the general principle of democracy, applied to the most pressing wants of the country … The government in a revolution is the despotism of liberty against tyranny.

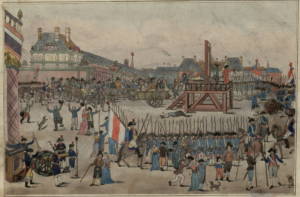

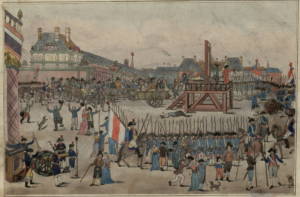

Victims of the Terror included prisoners in jails torn to pieces by mobs, boatloads of captives fired on by cannons, but mostly those who went in a stream to the execution machine set up the squares of most French cities. Nuns, priests, bourgeois, and former revolutionaries were beheaded by the guillotine after the flimsiest of trials. In 1794 a new law brought in by Robespierre and Antoine St-Just required the arrest of anyone on whom the slightest suspicion fell: “For a citizen to become suspect it is sufficient that rumour accuses him”. The new regulations denied the accused the right to counsel or any witnesses on their behalf; the only verdicts were acquittal or death. This new law also removed the immunity of Convention members from summary arrest, thus causing many politicians to feel threatened by the new system and by Robespierre and St-Just in particular. On July 27 (9 Thermidor on the new calendar) the Convention ordered the arrest of Robespierre and his clique. He attempted to commit suicide by shooting himself in the head with a pistol, but only succeeded in blowing off his jaw, causing him extreme pain. The next day, Robespierre, St-Just and 15 other radicals were guillotined without trial. With this so-called “Thermidorean Reaction” the Revolution became more conservative and less frightening.