1968

Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood”

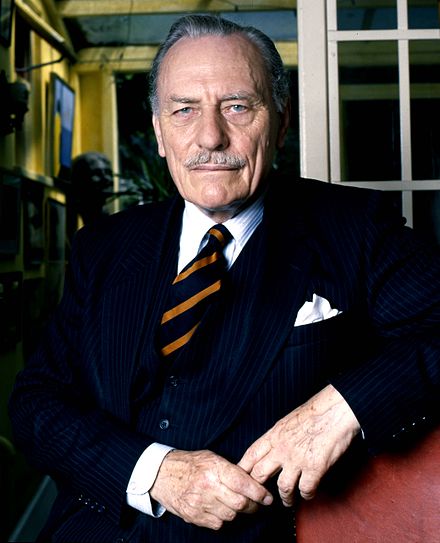

Enoch Powell (1912-98) was a brilliant classical scholar and linguist, a soldier who rose from the rank of private to general in the course of the Second World War, and a Conservative politician in the British House of Commons. In 1968 while his party was in Opposition, he gave a speech in his Birmingham constituency which opposed further non-white immigration from Commonwealth countries. It became known as the “Rivers of Blood” speech, after Powell’s reference to a passage in the Aeneid where the Sybil prophecies civil war.

As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding. Like the Roman, I seem to see “the River Tiber foaming with much blood”. That tragic and intractable phenomenon which we watch with horror on the other side of the Atlantic but which there is interwoven with the history and existence of the States itself, is coming upon us here by our own volition and our own neglect. Indeed, it has all but come. In numerical terms, it will be of American proportions long before the end of the century. Only resolute and urgent action will avert it even now. Whether there will be the public will to demand and obtain that action, I do not know. All I know is that to see, and not to speak, would be the great betrayal.

The speech was denounced by many in public life, including his fellow Conservative politicians; he was fired from his position as shadow defence critic. The general public seems to have been widely supportive at the time; polls backed his position, workers went on strike to protest his demotion, and letters to the editor were overwhelmingly in his favour. In the 1970 election, the Conservatives were returned to power and voting experts were convinced that Powell’s speech had added over two million votes to the winning party.

Because of the speech, Powell remained an outsider for the rest of his political life, opposing his party on entry into the European Union and on anti-terrorist legislation, and eventually running for the Ulster Unionists. The current debate on immigration levels has prompted many in the media to bring up Powell’s 1968 predictions again.