1528 The Obedience of a Christian Man

One of the greatest challenges that early Protestant reformers faced in persuading secular rulers of the value of the new religion was to assure kings that, despite their religious disobedience, they were perfectly harmless citizens. This was not always easy, given the way dissidents had claimed spiritual sanction for their violence in the German Peasant Rebellion.

Martin Luther wished to disassociate the evangelical cause from imputations of lawlessness and rebellion and return to the ideas held by the early Christians: obey superiors in all lawful commands but when ordered to perform any act against the will of God, refuse and suffer the legal consequences without murmur or complaint. Luther’s wish to deny the Catholic Church any coercive power tended to elevate the powers of the secular ruler; indeed Luther said that no one had spoken so highly of the magistracy since the days of the apostles as he had. The lot of Christians would ever be suffering and the cross; redress of oppression was to be sought only through prayer.

The early English reformers backed Luther on this point. William Tyndale, in his Obedience of a Christian Man, cited St. Paul’s words Romans 13 on obedience to the higher powers, castigated those who might suggest resistance and said that evil rulers were wholesome medicine, sent by God to chastise his people. In one remarkable passage he praises tyranny in comparison to the rule of a weak king:

It is better to pay the tenth than lose all. It is better to suffer one tyrant than many, and to suffer wrong of one man than of every man. Yea, and it is a better thing to have a tyrant unto thy king than a shadow; a passive king that doth nought himself, but suffereth others to do with him what they wi!, and to lead him whither they list. For a tyrant, though he do wrong unto the good, yet he punisheth the evil, and maketh all men obey, neither suffre any man to poll but himself only. A king that is soft as silk, and effeminate that is to say, turned into the nature of a woman,—what with his own lusts, which are the longing of a woman with child, so that he cannot resist them, and what with the wily tyranny of them that rule him, —shall be more grievous unto the realm than a right tyrant. Read the chronicles and thou shalt find it ever so.

Kings, added Tyndale, were above the law; they might do right or wrong as they willed and were accountable to no one but God.

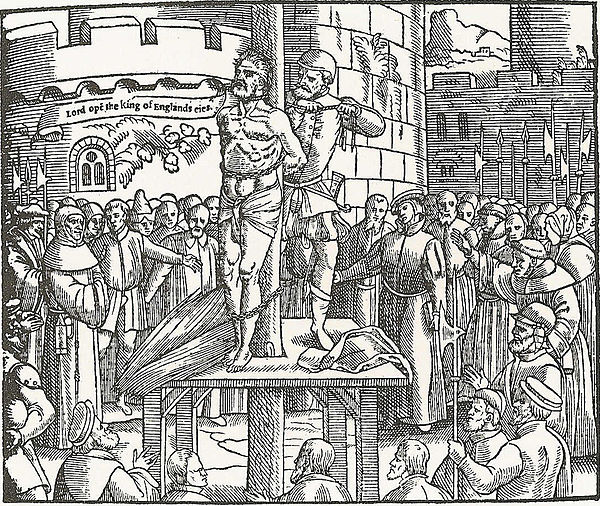

But, woe to poor obedient Tyndale. Despite fleeing religious persecution in England for his translation of the Latin Bible into the vernacular, he was arrested and burnt at the stake in 1536. His last words were “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.”