Pope Gregory VII

If saints are to be ranked by the sweetness of their character, Gregory VII, born Hildebrand of Soana (1020-85), must be placed very low on the celestial hierarchy. His belligerence and intolerance led to a clash between papacy and empire that cost many lives and led to centuries of strife.

Born into a peasant family, Hildebrand became a monk. His talents were recognized by a series of papal administrations in the mid-eleventh century, at a time when reforming zeal was sweeping the church. The chief abuse that came under attack was simony, which originally meant the corrupt buying and selling of church offices, but which now came to mean any kind of lay participation in the naming of church officials. For centuries it had been the custom for nobles, kings and emperors to have a hand in the selection of bishops, abbots, and even popes. In many countries, high-ranking clerics were an integral part of the feudal system, owning vast lands, paying feudal dues, and contributing to the provision of knights; for secular rulers to step back from appointing these men was unrealistic. Reforming clergy particularly took aim at rulers investing bishops with the staff and ring of office — thus the name “Investiture Controversy” for this whole collision of world views.

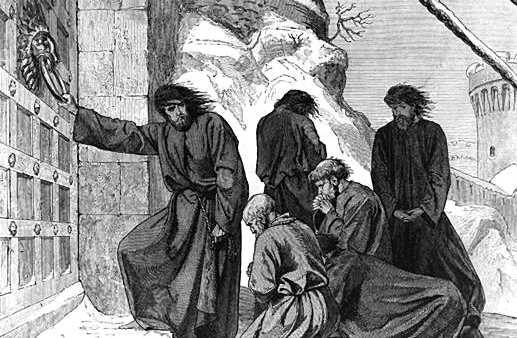

Hildebrand was among the chief supporters of popes who repudiated the role of the Holy Roman Emperor in naming pontiffs. He rose in administrative rank until finally in 1073 he was elected pope, taking the name Gregory VII. He immediately quarrelled with Emperor Henry IV. The young German king had political ambitions in northern Italy which clashed with those of the papacy and he refused to relinquish the power to name church officials. Denunciations were issued from each side, political allies were sought and bribed, apologies were made and retracted, and in 1076 Gregory excommunicated the emperor and declared his throne vacant. This forced Henry to wait in the snow outside the papal castle at Canossa (shown above) for a chance to abjectly debase himself in front of the pope in order to win back admission to the sacraments and to his throne. Once the ban was lifted, however, Henry resumed the fight which continued for the next ten years.

Gregory believed that the papacy was the natural ruler of Christendom and he held a low opinion of secular rulers. His intellectual circle engaged in a pamphlet war against the supporters of kings, probably the first controversy over political theory in western Europe since the fall of Rome. Gregory’s Dictatus papae of 1076 mandated that the princes of the world should kiss the feet of the pope, that the pope could depose emperors, and he could be judged by no man.

Needing a secular ally with an army to repel Henry’s invasion of papal lands, Gregory made an alliance with an unsavoury character, Robert Guiscard, a Norman bandit and adventurer who had made himself ruler of southern Italy. In 1084 Henry succeeded in capturing Rome and crowning a rival pope, forcing Gregory into hiding, but the Germans had to withdraw as the Norman army moved north. Guiscard liberated Gregory and occupied Rome but his troops behaved so badly that they were forced to flee, taking Gregory with them. The next year Gregory died in Salerno. On his tomb are the words: “I have loved justice and hated iniquity; therefore I die in exile.”