From Chambers’ Book of Days:

On 12th October 1492, Columbus with his followers landed on Guanahani or San Salvador, one of the Bahama Isles, and planted there the cross in token of gratitude to the Divine mercy, which, after guiding him safely through a perilous voyage, had at last, in the discovery of a western world, crowned with success the darling aspiration of his life. Land had already been descried on the previous evening, but it was not till the ensuing morning that the intrepid admiral beheld the flat and densely-wooded shores gleaming beneath the rays of an autumn sun, and by actually setting his foot on them, realized the fulfilment of his hopes.

It is now well known that although Columbus was unquestionably the first to proclaim to the world at large the existence of a new and vast region in the direction of the setting sun, he cannot literally be said to have been the first European discoverer of America. The ancient Scandinavians or Norsemen, so renowned for their maritime enterprise, had, at the commencement of the 11th century, not only settled colonies in Greenland, but explored the whole east coast of America as far south as lat. 41° 30′ N, and there, near New Bedford, in the state of Massachusetts, they planted a colony. An intercourse by way of Greenland and Iceland subsisted between this settlement and Norway down to the fourteenth century.

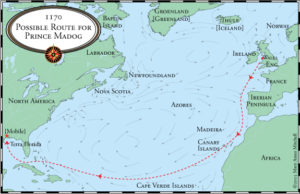

There is also satisfactory evidence for believing, that in the twelfth century the celebrated Welsh prince, Madoc, having sailed from his native country with a small fleet, landed and founded a colony on the coast of Virginia. But to Columbus still belongs the merit of having philosophically reasoned out the existence of a New World, and by practically ascertaining the truth of his propositions, of inaugurating that connection between the Eastern and Western Hemispheres which has effected so remarkable a revolution in the world’s history.

The story of Prince Madoc continues to fascinate. Check out this site for the possibility of a tribe of Welsh Indians: https://www.thestar.com/news/insight/2007/07/22/will_dna_turn_madoc_myth_into_reality.html