1100

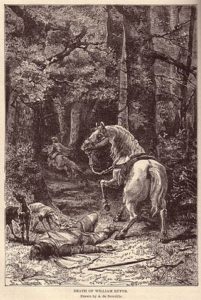

Death of William II aka Rufus

William II, nicknamed Rufus because of his red hair, was a son of William the Conqueror and became King of England after his father’s death in 1087. The chief event of his reign was his disastrous naming of Anselm of Bec as his Archbishop of Canterbury. Anselm was a man of integrity, interested in reforming the church and opposing royal meddling; he soon quarrelled with Rufus and went into exile. Anselm became a saint and Rufus died a strange and somewhat ironic death, recounted here by Chambers with particular reference to forest law. The Normans after their 1066 conquest of England fenced off huge tracts of the countryside and dedicated them to royal hunting. A whole set of laws was dedicated to policing these territories and punishing any commoner who entered.

Few Englishmen of the nineteenth century can realize a correct idea of the miseries endured by their forefathers, from the game-laws, under despotic princes. Constant encroachments upon private property, cruel punishments—such as tearing out the offender’s eyes, or mutilating his limbs—inflicted for the infraction of forest law; extravagant payments in the shape of heavy tolls levied by the rangers on all merchandise passing within the purlieus of a royal chase; frequent and arbitrary changes of boundary, in order to bring offences within the forest jurisdiction, were only a portion of the evils submitted to by the victims of feudal tyranny. No dogs, however valuable or dear to their owners—except mastiffs for household defence —were allowed to exist within miles of the outskirts, and even the poor watch-dog, by a ‘Court of Regard’ held for that special purpose every three years, was crippled by the amputation of three claws of the forefeet close to the skin—an operation, in woodland parlance, termed expeditation, intended to render impossible the chasing or otherwise incommoding the deer in their coverts.

Of all our monarchs of Norman race, none more rigorously enforced these tyrannous game-laws than William Rufus; none so remorselessly punished his English subjects for their infraction. Even the Conqueror himself, who introduced them, was more indulgent. No man of Saxon descent dared to approach the royal preserves, except at the peril of his life with the trespasser hung up to the nearest convenient tree with his own bowstring.

The poor Saxons, thus worried, adopted the impotent revenge of nicknaming Rufus ‘Wood-keeper,’ and ‘Herdsmen of wild beasts.’ Their minds, too, were possessed with a rude and not unnatural superstition, that the devil in various shapes, and under the most appalling circumstances, appeared to their persecutors when chasing the deer in these newly-formed hunting -grounds. Chance had made the English forests—the New Forest especially—fatal to no less than three descendants of their Norman invader, and the popular belief in these demon visitations received additional confirmation from each recurring catastrophe; Richard, the Conqueror’s eldest son, hunting there, was gored to death by a stag; the son of Duke Robert, and nephew of Rufus, lost his life by being dashed against a tree by his unruly horse; and we shall now shew how Rufus himself died by a hunting casualty in the same place.

Near Chormingham, and close to the turnpike-road leading from Lymington to Salisbury, there is a lovely secluded dell, into which the western sun alone shines brightly, for heavy masses of foliage encircle it on every other side. It is, indeed, a popular saying of the neighbourhood: that in ancient days a squirrel might be hunted for the distance of six miles, without coming to the ground; and a traveller journey through a long July day without seeing the sun. On this day in 100 the king and friends went hunting. Some of the party had dispersed to various coverts, and there remained alone with Rufus, Sir Walter Tyrrel, a French knight, whose unrivalled adroitness in archery raised him high in the Norman Nimrod’s favour. That morning, a workman had brought to the palace six cross-bow quarrels of superior manufacture, and keenly pointed, as an offering to his prince. They pleased him well, and after presenting to the fellow a suitable reward, he handed three of the arrows to Tyrrel—saying, jocosely, ‘Bon archer, bonnes flèches.’

The Red King and his accomplished attendant now separated, each stationing himself, still on horseback, in some leafy covert, but nearly opposite; their cross-bows bent, and with an arrow upon the nut. The deep mellow cry of a stag hound, mingled with the shouts of attendant foresters, comes freshening on the breeze. There is a crash amongst the underwood, and out bounds ‘a stag of ten,’ that after listening and gazing about him, as deer are wont to do, commenced feeding behind the stem of a tall oak. Rufus drew the trigger of his weapon, but, owing to the string breaking, his arrow fell short. Enraged at this, and fearful the animal would escape, he exclaimed, Tirez done, Walter! tirez done! si mĕme cètoit le diablé—Shoot, Walter! shoot! even were it the devil. His behest was too well obeyed; for the arrow glancing off from the tree at an angle, flew towards the spot where Rufus was concealed. A good arrow, and moreover a royal gift, is always worth the trouble of searching for, and the archer went to look for his. The king’s horse, grazing at large, first attracted attention; then the hounds cowering over their prostrate master; the fallen cross-bow; and, last of all, the king himself prone upon his face, still struggling with the arrow, which he had broken off short in the wound. Terrified at the accident, the unintentional homicide spurred his horse to the shore, embarked for France, and joined the Crusade then just setting for the East.

About sun-down, one Purkiss, a charcoal-burner, driving homewards with his cart, discovered a gentleman lying weltering in blood, with an arrow driven deep into his breast. The peasant knew him not, but conjecturing him to be one of the royal train, he lifted the body into his vehicle, and proceeded towards Winchester Palace, the blood all the way oozing out between the boards, and leaving its traces upon the road.

More than one historian has suggested that this might have been a murder instigated by Rufus’s younger brother Henry who was in the hunting party and who instantly seized the crown.