Yule was the time amongst the pagan Teutons for the sacrifice of a white horse. Christmas too has ceremonies that focus on horses, though not in such a fatal fashion.

For reasons that remain unclear St Stephen has come to be regarded as the patron saint of horses and therefore his day, December 26, is given over to horse parades, races and special treatment for the animals.

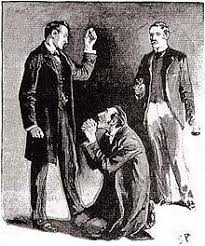

In Wales the Mari Llwyd (“Grey Mare”, pictured above) ceremony involves a man under a white sheet carrying a pole topped by a horse’s head with snapping jaws — it capers, ringing the bells on its sheet, and bites people who have to pay a forfeit to be released. According to legend, the Mari Lwyd is the animal turned out of its stable to make room for the Holy Family; it has been looking for shelter ever since. Accompanied by a group of men, often in mummers’ costumes or bearing bells the Mari Lwyd will approach a house during the Christmas season and the group will beg admittance. After a ritual negotiation that may involve the exchange of humourous verses they will be let inside where the horse will dart about while hospitality is shared.

In England similar horse figures are Old Hob, who went about with a group of men singing and ringing hand bells for a gratuity, and the Hodening Horse of Kent. On the Isle of Man it is the Laare Vane or White Mare which appeared on New Year’s Eve.

In Germany the hobby-horse is called Schimmel (or in some places Schimmelreiter to emphasize the rider). Like the Mari Lwyd it takes part in house visits; jumping about to entertain the children and dancing with pretty girls.