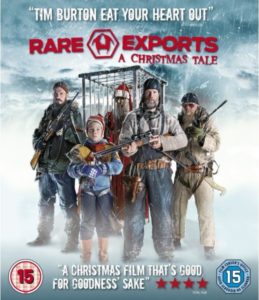

Rare Exports (2010). I know. You are saying to yourself, “What?! Has Bowler taken leave of his senses? How can he place this obscure Finnish comedy-horror movie so high in the pantheon of Christmas films?” Because it’s that good. Forget It’s A Wonderful Life, Christmas Story, The Santa Clause, and Miracle on 34th St for a moment and cast your peepers on this. It’s full of love, lore, humour, sacrifice and, best of all, a look at the scary Christmas figures that we have tried to forget once ruled the darkest time of the year. Not for little kids but pre-teens will enjoy it.

The Best Christmas movie ever made

A Christmas Carol (1951) They don’t get any better than this. Alastair Sim is the definitive Scrooge and anyone else who attempts the part should be boiled with his own pudding, and buried with a stake of holly through his heart. Sim’s Scrooge is a grim and shrivelled miser, miserable in his petty economies and cruel to those who imagine that generosity is anything else but a form of weakness. His experiences at the hands of the Spirits of Christmas are harrowing — this is, after all, a ghost story — they wrench the emotions and lead to changes that redeem the old sinner and lift the hearts of audiences.

Director Brian Desmond-Hurst’s settings in foggy and candle-lit London are masterful and the best argument for leaving black-and-white films in their original state. (Avoid the garishly-tinted colourized version that appears too frequently on television screens.) This motion picture was titled Scrooge in the U.K.

Sim and Michael Hordern (Marley’s ghost) repeated their roles in a 1972 animated version directed by Chuck Jones and narrated by Michael Redgrave which won an Oscar for best short animation.

The Christmas Cat

The pet of the ogre Gryla in Icelandic folklore. According to a rather peculiar piece of folk wisdom, those who do not get an item of new clothing for Christmas are liable to be eaten by this monstrous feline. The explanation is that all those who helped get the year’s spinning and knitting done would be rewarded with clothing but the lazy would not. The Christmas Cat was therefore an inducement to hard work and cooperation.

Gryla and Leppaludi

The parents of the Jólasveinar are Gryla and Leppaludi, cannibals of whom it is impossible to say anything nice. The tales of these ogres were so blood-chilling that the Danish government which ruled Iceland in the eighteenth century legislated in 1746 against using these stories to frighten children.

Seasonal complaints

Many people today, Christian and non-Christian alike, complain about the commercialism and degradation of Christmas. In a 380 Christmas sermon, Gregory of Nazianzen, the archbishop of Constantinople, decried the way the Romans behaved during their late December celebrations:

Let us not put wreaths on our front doors, or assemble troupes of dancers, or decorate the streets. Let us not feast the eyes, or mesmerize the sense of hearing, or make effeminate the sense of smell, or prostitute the sense of taste, or gratify the sense of touch. These are ready paths to evil, and entrances of sin … Let us not assess the bouquets of wines, the concoctions of chefs, the great cost of perfumes. Let earth and sea not bring us as gifts the valued dung, for this is how I know to evaluate luxury. Let us not strive to conquer each other in dissoluteness. For to me all that is superfluous and beyond need is dissoluteness, particularly when others are hungry and in want, who are of the same clay and composition as ourselves. But let us leave these things to the Greeks and to Greek pomp and festivals.

Why December 25?

The notion that Christmas was situated on December 25 by the early church because of the date’s connection to the winter solstice and sun worship has no contemporary evidence for it. The earliest we hear of it is in this 12th-century Syriac manuscript:

The Lord was born in the month of January, on the day on which we celebrate the Epiphany [January 6]; for the ancients observed the Nativity and the Epiphany on the same day, because he was born and baptized on the same day. Also still today the Armenians celebrate the two feasts on the same day. To this must be added the Doctors who speak at the same time of the one and the other feast. The reason for which the Fathers transferred the said solemnity from the sixth of January to the 25th of December is, it is said, the following: it was the custom of the pagans to celebrate on this same day of the 25th of December the birth of the sun. To adorn the solemnity, they had the custom of lighting fires and they even invited Christians to take part in these rites. When, therefore, the Doctors noted that the Christians were won over to this custom, they decided to celebrate the feast of the true birth on this same day; the 6th of January they made to celebrate the Epiphany. They have kept this custom until today with the rite of the lighted fire.

It is almost certainly not a true explanation but you still it attested to on the Web.

St Nicholas as magical Gift-Bringer

Night of the Screams

In Nicaragua, Christmas begins December 7 with the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, known in Spanish as “La Purísima” (The Most Pure). The exuberance and the loudness of the festivities is such that it has also come to be called “La Noche de Gritería”, the Night of the Screams. Songs are sung at maximum volume, fireworks are set off and crowds shout out questions and responses: “Quien causa tanta alegría?” — “Why all this happiness? — “La Concepción de María!” — “The Conception of Mary!” — “Viva la Concepcio!” — “Long live the Conception!” Homeowners hand out out candies, fruit and little treats to the crowds who will party until dawn.

St Nicholas Day

The patron saint of Aberdonians, apothecaries, Austrians, bakers, barrel-makers, boatmen, Belgians, boot-blacks, brewers, brides, butchers, button-makers, captives, chandlers, children, coopers, dock workers, Dutchmen, druggists, firemen, fishermen, florists, folk falsely-accused, Greeks, grooms, haberdashers, judges, Liverpudlians, longshoremen, merchants, murderers, newlyweds, notaries, old maids, orphans, parish clerks, paupers, pawnbrokers, perfumers, pharmacists, pilgrims, pirates, poets, rag pickers, Russians, sailors, sealers, shipwrights, Sicilians, spice dealers, students, thieves, travellers, and weavers.

St Maximus of Turin

As people begin to grumble about Christmas stress, it’s time to remind them of the words of St Maximus of Turin, 1600 years ago:

You well know what joy and what a gathering there is when the birthday of the emperor of this world is to be celebrated; how his generals and princes and soldiers, arrayed in silk garments and girt with precious belts worked with shining gold, seek to enter the king’s presence in more brilliant fashion than usual …If, therefore, brethren, those of this world celebrate the birthday of an earthly king with such an outlay for the sake of the glory of the present honor, with what solicitude ought we to celebrate the birthday of our eternal king Jesus Christ. Who in return for our devotion will bestow on us not temporal but eternal glory.