1799

The fall of Seringapatam

In the 18th century, India was divided into a multitude of princely states, many of whom were allied with the British East India Company, and others who were more jealous of their independence. One of the most important of the latter was the Kingdom of Mysore, ruled by Tipu Sultan, an energetic and innovative ruler who persecuted non-Muslims, despised the British and who had led several wars against them. He attempted to recruit the Turkish Empire and Napoleon’s French armies into an alliance against the East India Company. In the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War Tipu fell defending his fortress at Seringapatam. Chambers describes the situation thusly:

On the 4th of May 1799, Seringapatam was taken, and the empire of Hyder Ally extinguished by the death of his son, the Sultan Tippoo Sahib. The storming of this great fortress by the British troops took place in broad day, and was on that account unexpected by the enemy. The commander, General Sir David Baird, led one of the storming parties in person, with characteristic gallantry, and was the first man after the forlorn hope to reach the top of the breach. So far, well; but when there, he discovered to his surprise a second ditch within, full of water. For a moment he thought it would be impossible to get over this difficulty. He had fortunately, however, observed some workmen’ s scaffolding in coming along, and taking this up hastily, was able by its means to cross the ditch; after which all that remained was simply a little hard fighting. Tippoo came forward with apparent gallantry to resist the assailants, and was afterwards taken from under a heap of slain. It is supposed he made this attempt in desperation, having just ordered the murder of twelve British soldiers, which he might well suppose would give him little chance of quarter, if his enemy were aware of the fact.

It was remarkable that, fifteen years before, Baird had undergone a long and cruel captivity in this very fort, under Tippoo’ s father, Hyder Ally. The hardships he underwent on that occasion were extreme; yet, amidst all his sufferings, he never for a moment lost heart, or ceased to hope for a release. He was truly a noble soldier. As with Wellington, his governing principle was a sense of duty. In every matter, he seemed to be solely anxious to discover what was right to be done, that he might do it. He was a Scotchman, a younger son of Mr. Baird, of Newbyth, in East Lothian (born in 1757, died in 1829). His person was tall and handsome, and his look commanding. In all the relations of his life he was a most worthy man, his kindness of heart winning him the love of all who came in contact with him.

An anecdote of Sir David Baird’s boyhood forms the key to his character. When a student at Mr. Locie’ s Military Academy at Chelsea, where all the routine of garrison duty was kept up, he was one night acting as sentinel. A companion, older than himself, came and desired leave to pass out, that he might fulfil an engagement in London. Baird steadily refused— ‘No,’ said he, ‘that I cannot do; but, if you please, you may knock me down, and walk out over my body.’

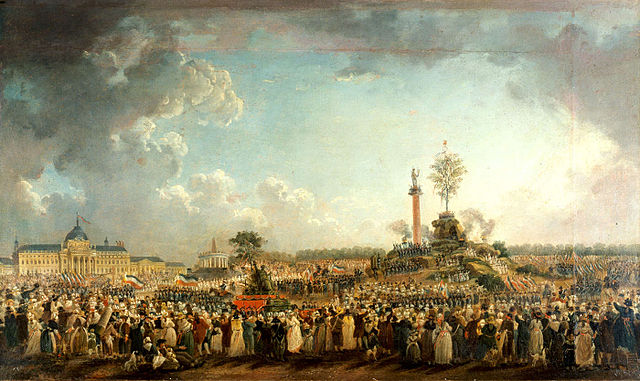

The taking of Seringapatam gave occasion for a remarkable exercise of juvenile talent in a youth of nineteen, who was studying art in the Royal Academy. He was then simply Robert Ker Porter, but afterwards, as Sir Robert, became respectfully known for his Travels in Persia; while his two sisters Jane and Anna Maria, attained a reputation as prolific writers of prose fiction. There had been such a thing before as a panorama, or picture giving details of a scene too extensive to be comprehended from one point of view; but it was not a work entitled to much admiration. With marvelous enthusiasm this boy artist began to cover a canvas of two hundred feet long with the scenes attending the capture of the great Indian fort; and, strange to say, he had finished it in six weeks. Sir Benjamin West, President of the Royal Academy, got an early view of the picture, and pronounced it a miracle of precocious talent.

When it was arranged for exhibition, vast multitudes both of the learned and the unlearned flocked to see it. ‘I can never forget,’ says Dr. Dibdin,’ its first impression upon my own mind. It was as a thing dropped from the clouds,—all fire, energy, intelligence, and animation. You looked a second time, the figures moved, and were commingled in hot and bloody fight. You saw the flash of the cannon, the glitter of the bayonet, and the gleam of the falchion. You longed to be leaping from crag to crag with Sir David Baird, who is hallooing his men on to victory! Then again you seemed to be listening to the groans of the wounded and the dying—and more than one female was carried out swooning. The oriental dress, the jewelled turban, the curved and ponderous scimitar—these were among the prime favourites of Sir Robert’s pencil, and he treated them with literal truth. The colouring was sound throughout; the accessories strikingly characteristic The public poured in thousands for even a transient gaze.’