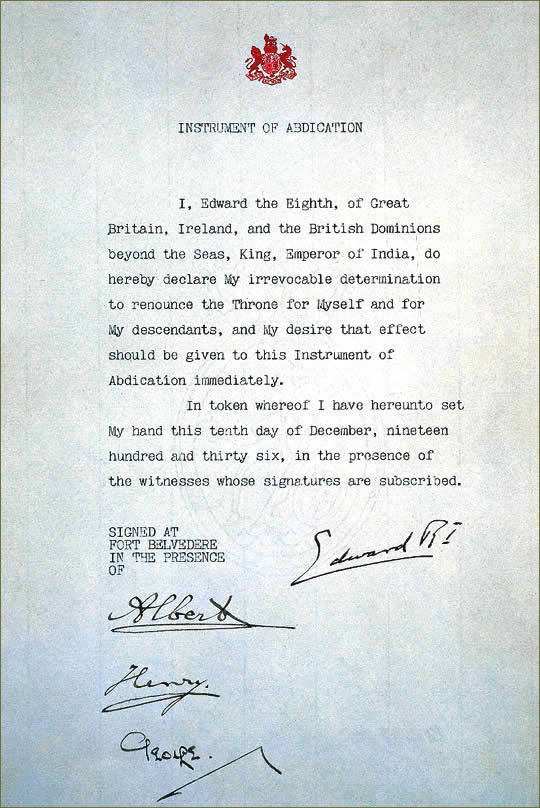

1937 Edward VIII’s abdication becomes official

There is a long history of antipathy between English monarchs and his heirs, particularly when the son has had to wait many years for their father to pass away. Henry II had to fight wars with three of his sons, and the mutual hatred between the Hanoverian dynasts George I, II, III and IV is legendary. Queen Victoria had little respect for her son (she said, “I never can, or shall, look at him without a shudder”) and so the future Edward VII led a long life of dissipation as the Prince of Wales (he was 60 years old when his mother died.) And so it was with Prince Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David, the heir to George V.

“David”, as he was known to his family, was a very popular Prince of Wales, representing the royal family in world tours and visits to parts of Britain. He was a handsome young man and remained unmarried past an age where earlier princes had been advantageously wed. His association with women of ill-repute and his affairs with married women were notorious and troubling to his parents and the government. In 1931 he met an American woman, Wallis Simpson, whose previous husband was a navy pilot and who was still married to a shipping executive. They began a romance that would shake the British empire. To this day, historians still puzzle over the hold Wallis held over her lover with rumours of domination, sexual secrets of the mystic East, and physical deformity all considered.

In January 936 George V died and David became king, with the regnal title Edward VIII. He was uncomfortable with the restrictions that kingship placed on him, particularly where his love life was concerned. By this time his relationship with the twice-married American was a scandal in the press outside of Britain (where the newspapers still kept royal secrets) and a troubling constitutional question. As head of the Church of England, which did not allow remarriage after divorce, Edward would be jeopardising his relationship with the national church, and in any event, Simpson was still married and her first divorce was on shaky legal ground in the United Kingdom. Would the king be committing both adultery and bigamy?

It is quite likely that Simpson would have been happy to remain the King’s mistress (that sort of relationship was considered quite acceptable to the upper classes) but Edward was determined to make her his wife. His family was opposed, the British government and those of the Dominions, such as Canada, were also against such a union. Edward suggested a compromise — a “morganatic union” where Wallis would not be termed Queen and any children would not be considered in the line of succession but the politicians turned him down. He resolved then to abdicate.

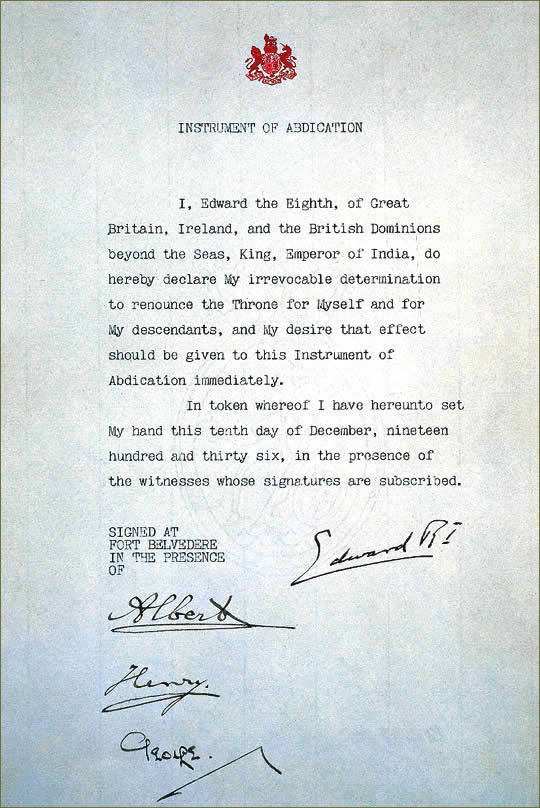

On December 10, 1937 he signed the above document which became official the next day. His brother ascended the throne as George VI and Edward left the country as the Duke of Windsor. Wallis would join him later when her second divorce became final.

This love story had a long tawdry ending. The Windsors were courted by the German Nazis and there was talk of Edward being sympathetic to their cause. During the Second World War he was allowed no post of any importance and was humiliatingly posted as Governor of the Bahamas to get him out of the way. The couple lived a life of impoverished ostentation in a luxurious Paris house, forbidden for years to return to Britain. One historian summed up their end: “Denied dignity, and without anything useful to do, the new Duke of Windsor and his Duchess would be international society’s most notorious parasites for a generation, while they thoroughly bored each other”.