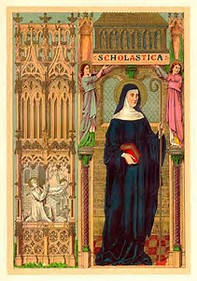

842 The Restoration of Icons

For almost a century, the Eastern Christian world was split over the proper use of images in worship. The Ten Commandments expressly forbade the creation of “graven images” and Judaism developed as an aniconic faith, eschewing the visual representation of God as a form of idolatry.

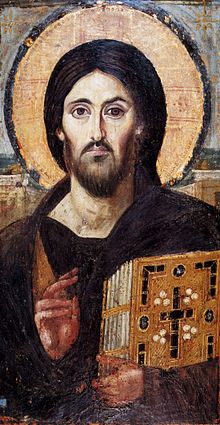

Christians, however much they rejected the worship of idols, felt it was necessary to portray the Godhead inasmuch as Christ had come to earth in human form. To reject depicting him was to fall prey to the Docetic heresy, which claimed that Jesus had only appeared to be human and to reject the goodness of the created world. Thus Christianity developed a rich visual art tradition. This tradition was particularly strong in the East where icons of Jesus and the saints were treated with intense devotion.

When Christian forces suffered losses in the Middle East at the hands of Muslim invaders, many military officers from the border areas began to believe that the Islamic refusal to depict God was a reason for their success; Christianity had fallen into idolatry and was being punished. When one of these generals, Leo III, became emperor he began a period of iconoclasm, a policy followed by his successor Constantine V. Images were destroyed, defaced or painted over, causing popular outrage and clashes with the monasteries which were devotees of images. Ironically, the greatest intellectual supporter of icons was John of Damascus who lived in Muslim-occupied Syria.

For a short time at the end of the century under Empress Irene, icons were restored but the army continued to oppose them. When she was overthrown, iconoclasm was resumed. It was not until February 19, 842, that were icons restored to the churches largely at the instigation of the Empress Theodora. The first Sunday of Lent is still observed as the “Feast of Orthodoxy” in Eastern churches.

The iconoclastic spirit was strong in 16th and 17th century Protestantism which carried out much regrettable destruction of religious art. The current brouhaha over the depiction of the Muslim prophet Mohammed shows the issue is still very much alive.

The icon above is of Christ Pantocrator (Almighty), from the 6th century in the St Catherine monastery, Mount Sinai.