1606

The trial of Henry Garnet, SJ

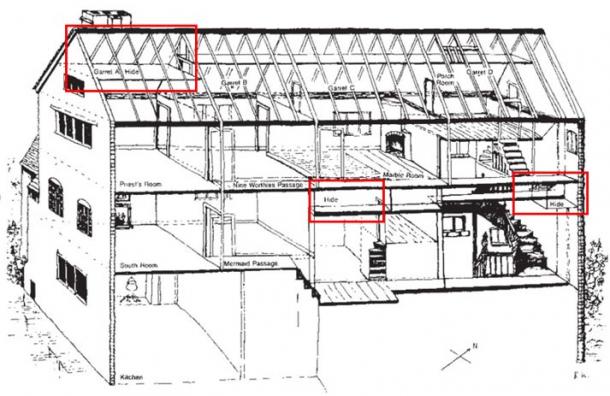

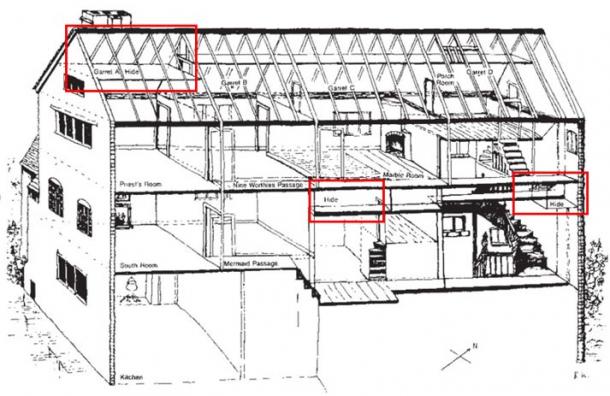

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 was a plan by English Catholics to blow up Parliament, killing all its Members, the heads of the aristocracy, the Protestant bishops, and the royal family. Though the bombs were successfully placed, the conspirators were apprehended before the terroristic atrocity could be carried out. The English government arrested the leading plotters but was intent on uncovering the role played by Catholic priests, particularly Jesuits in encouraging the murders. Especially sought was Henry Garnet (1555-1606), chief of the priests of the Society of Jesus that had been smuggled into the country. Informants revealed that Garnet was probably hiding with a Catholic family in the countryside and that, as was common, the house in which he was staying had a “priest hole” to conceal him in case of a search. The following passage describes the search of Hindlip Hall in Worcestershire.

When Father Garnet came to be inquired after, the government, suspecting Hendlip to be his place of retreat, sent Sir Henry Bromley thither, with instructions which reveal to us much of the character of the arrangements for the concealment of priests in England. ‘In the search,’ says this document, ‘first observe the parlour where they use to dine and sup; in the east part of that parlour it is conceived there is some vault, which to discover you must take care to draw down the wainscot, whereby the entry into the vault may be discovered. The lower parts of the house must be tried with a broach, by putting the same into the ground some foot or two, to try whether there may be perceived some timber, which, if there be, there must be some vault underneath it. For the upper rooms, you must observe whether they be more in breadth than the lower rooms, and look in which places the rooms be enlarged; by pulling up some boards, you may discover some vaults. Also, if it appear that there be some corners to the chimneys, and the same boarded, if the boards be taken away there will appear some. If the walls seem to be thick, and covered with wainscot, being tried with a gimlet, if it strike not the wall, but go through, some suspicion is to be had thereof. If there be any double loft, some two or three feet, one above another, in such places any may be harboured privately. Also, if there be a loft towards the roof of the house, in which there appears no entrance out of any other place or lodging, it must of necessity be opened and looked into, for these be ordinary places of hovering [hiding].’

Sir Henry invested the house, and searched it from garret to cellar, without discovering anything suspicious but some books, such as scholarly men might have been supposed to use. Mrs. Abingdon—who, by the way, is thought to have been the person who wrote the letter to Lord Monteagle, warning him of the plot—denied all knowledge of the person searched for. So did her husband when he came home. ‘I did never hear so impudent liars as I find here,’ says Sir Henry in his report to the Earl of Salisbury, forgetting how the power and the habit of mendacity was acquired by this persecuted body of Christians. After four days of search, two men came forth half dead with hunger, and proved to be servants.

Sir Henry occupied the house for several days more, almost in despair of further discoveries, when the confession of a conspirator condemned at Worcester put him on the scent for Father Hall, as for certain lying at Hendlip. It was only after a search protracted to ten days in all, that he was gratified by the voluntary surrender of both Hall and Garnet. They came forth from their concealment, pressed by the need for air rather than food, for marmalade and other sweetmeats were found in their den, and they had had warm and nutritive drinks passed to them by a reed ‘through a little hole in a chimney that backed another chimney, into a gentlewoman’s chamber.’ They had suffered extremely by the smallness of their place of concealment, being scarcely able to enjoy in it any movement for their limbs, which accordingly became much swollen. Garnet expressed his belief that, if they could have had relief from the blockade for but half a day, so as to allow of their sending away books and furniture by which the place was hampered, they might have baffled inquiry for a quarter of a year.