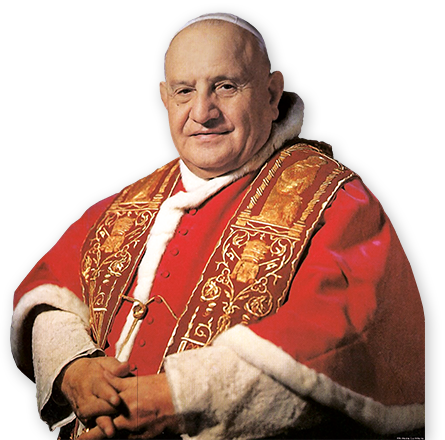

Pope John XXIII opens Vatican II

Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli (1881-1963) was born to a peasant family in northern Italy. Despite his humble origins and a wartime spell as a stretcher bearer, Roncalli rose quickly though the Catholic hierarchy. He served as an aide to prominent clerics and was appointed to a number of diplomatic posts, representing the Vatican in Greece, Bulgaria, Turkey and France. During the Second World War he assisted in rescuing Jews from Nazi persecution and negotiated the resignation of bishops who had sided with German occupation.

In 1953 he was appointed to the College of Cardinals and the Archbishopric of Venice. On the death of Pope Pius XII in 1958 Roncallli was 77 years old, which may have been seen as a good thing in the eyes of the electors of the next pope who could see him as a safe, short-term choice. After 11 ballots he was elevated to the See of Peter and surprisingly took the name of John — surprising because there had not been a “John” on the papal throne since the early 1400s and that incumbent was seen as an “anti-pope”, an illegitimate claimant to the papacy, guilty of piracy, rape, sodomy, murder and incest. To complicate matters, this last John was called the twenty-third of that name but that was a miscount (there had been no John XX). Roncallli chose to be called John XXIII, which was mathematically correct.

Those who expected an elderly do-nothing pope were astonished at John’s energy and charity — he visited prisons and children’ hospitals as part of his pastoral duties. Even more, he shocked the world with his audacity, summoning a Council of the Church to meet in October 1962 and charged it with the task of addressing the relationship of the Church and modern society. Though he did not live to see its conclusion, John’s Second Vatican Council revolutionized the Mass, opened up ecumenical dialogue and set in chain a series of changes that are still being debated.

John’s most famous encyclical was Pacem in Terris of 1963, completed shortly before his death, but he is best known for his engaging personality and openness. He was canonized in 2002 by Pope John Paul II.