1525

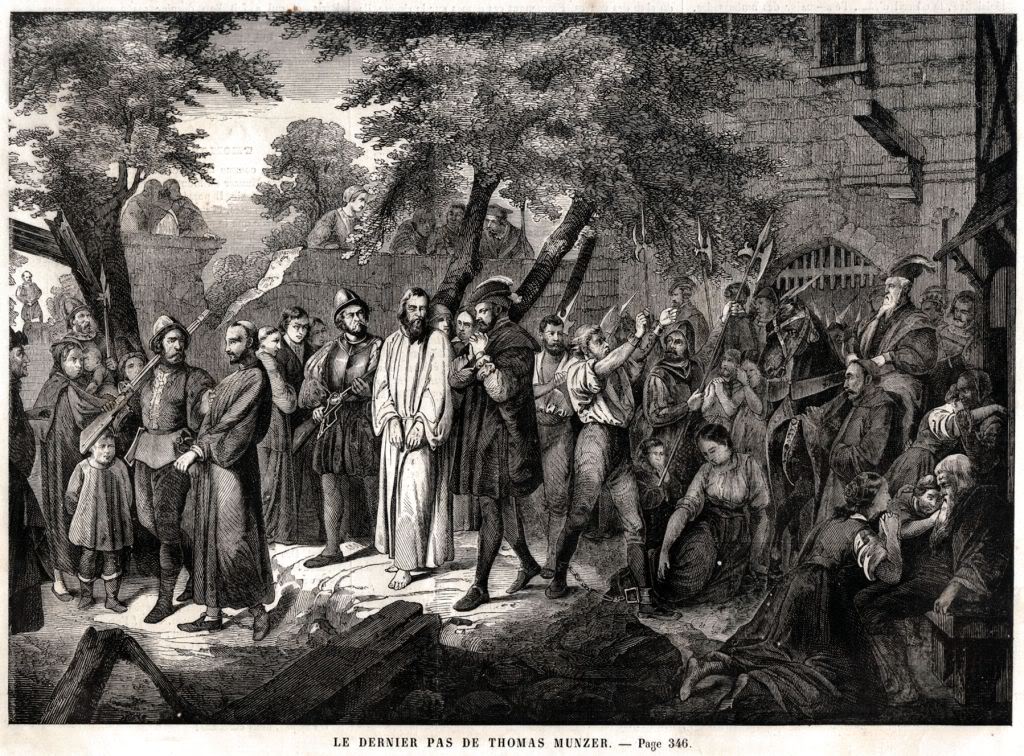

The execution of Thomas Müntzer

When Martin Luther stood before the Holy Roman Emperor in 1521, he asserted that one man’s conscience, formed by reading the Bible, could stand against the might of the Church and a thousand years of tradition. His Catholic opponents argued that individual interpretation of Scripture would lead to chaos and a multitude of opinions, many of them erroneous and heretical. And so it came to be. While Luther was fleeing into hiding after his trial, a host of wild men with wild ideas, sprang up across the German-speaking lands – some of them even entered into Wittenberg where Luther had taught. These were the “Zwickau Prophets” who claimed that Luther had not gone nearly far enough in his rejection of established religion, for what mattered was not Scripture but the direct inspiration of the Holy Spirit. These “Spiritualists” argued that God came in the form of visions and dreams, not in the words of an old book, and they caused the chaos that the Catholics had predicted.

One such Spiritualist was Thomas Müntzer (1489-1525), a priest who was already deemed a radical even before he met, and studied with, Luther. As he wandered from town to town, looking for an audience that would respond to his views, Müntzer became convinced that that End Times were at hand. Christ’s Second Coming was not long off (a widely-held belief even professed by Luther) but that His coming must be preceded by a bloody cleansing of the earth wherein the enemies of Christ: priests, princes, nobles and those who did not follow this Spiritualist line, would be killed. Following the cleansing all would be equal and all property would be held in common.

Peasants in the 16th century were seeing their traditional rights eroded: from hunting and fishing to representation at local diets. Peasants had long used biblical and religious justification to back their anti-feudal demands. For decades the Bundschuh (peasant legging and shoe) had served as the symbol of peasant resistance and striving in dozens of local rebellions. The Bundschuh was often linked with a religious slogan which implied that God’s laws were not being followed by their feudal overlords and so peasants knew how to exploit a cognate theological argument for spiritual freedom when they heard it in Lutheran sermons. When Luther in 1523 urged communities to pick their own pastors, peasant leaders claimed his approval for local political control as well. There was, therefore, mutual exploitation during these years: the Lutherans by the peasants, and the peasants by the Lutherans. Reformers sought to enlist the support of the peasants and portrayed farmer Hans with his plough as the ideal Christian, the sort of man that God intended: working with his hands, not puffed up with vain theological knowledge. Luther urged lords to treat their peasants as fellow Christians and not to exploit them lest they rise in rebellion but there was no way that mainstream reformers could sanction peasant rebels when fighting broke out in late 1524.

The first outbreak came in Stühlingen where, in the middle of the harvest, the countess demanded that the peasants stop taking off the crop and search for snail shells for her (she was going to wind yarn around them). The fighting spread in Switzerland and across much of Germany. The reasons for the rebellion were overwhelmingly economic and social but there was a religious element too and an involvement by reforming preachers. The “Twelve Articles” which became the peasant manifesto included the demand that local communities have the right to name their own pastors and vowed that they wanted no reform that was not according to Holy Scripture.

Thomas Müntzer had by 1525 become one of the leaders of the rebellion. He began to style himself “Destroyer of the Unbelievers” and to preach of the imminent end of the old era and the dawn of a new age of social justice. His appeal to German princes to lead his crusade having fallen on deaf ears, Müntzer turned to the poor to be the new Elect, a covenanted people of God. When the rebellion broke out he urged his poor followers on to violence and a liberating slaughter that would open the way to the new age of godliness and peace.

Luther began by urging peace and moderation – criticizing both the lords for their refusal to recognize the justice of some of the peasant demands and the peasants for using violence to further their ends. He personally mediated some disputes and pacified areas at the risk of his own life but in 1525 when news of peasant atrocities reached him he turned decisively against them. The title of his work Against the Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants pretty much tells the tale. He urged the authorities to repress the rebels like mad dogs and to show no mercy until the rebellion had been crushed. By the time Luther’s book appeared the fighting was over. The critical battle took place at Frankenhausen where Müntzer was urging violence every bit as harsh as Luther. “On! On! On!”, he told the peasant soldiers, “Spare not. Pity not the godless when they cry. Remember the command of God to Moses to destroy utterly and show no mercy. The whole countryside is in commotion. Strike! Clang! Clang! On! On!” He told the peasants that he would precede them and catch their enemies’ bullets in his sleeves but in fact he ran away and was hiding in bed when he was captured by the forces of the triumphant princes. He was executed on this day in 1525.