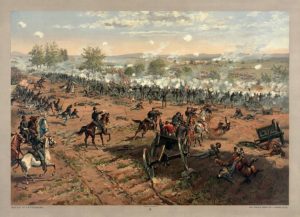

1863 Pickett’s Charge

For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it’s still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863, the brigades are in position behind the rail fence, the guns are laid and ready in the woods and the furled flags are already loosened to break out and Pickett himself with his long oiled ringlets and his hat in one hand probably and his sword in the other looking up the hill waiting for Longstreet to give the word and it’s all in the balance, it hasn’t happened yet, it hasn’t even begun yet, it not only hasn’t begun yet but there is still time for it not to begin against that position and those circumstances which made more men than Garnett and Kemper and Armistead and Wilcox look grave yet it’s going to begin, we all know that, we have come too far with too much at stake and that moment doesn’t need even a fourteen-year-old boy to think “This time”. Maybe this time with all this much to lose than all this much to gain: Pennsylvania, Maryland, the world, the golden dome of Washington itself to crown with desperate and unbelievable victory the desperate gamble, the cast made two years ago.

Thus wrote William Faulkner about the bloody events of July 3, 1863, when the Battle of Gettysburg was lost to the Southern cause, when thousands of rebel infantrymen were blown to bits trudging the three quarters of mile under ferocious fire toward the Union lines.

Robert E. Lee’s invasion of the North was met and blunted at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania by General George Meade. Most historians regard the three-days of fighting at Gettysburg as the turning point of the American Civil, the last time at which the South could realistically contemplate victory, and they look upon Pickett’s Charge as the moment the battle was decisively settled.

Lee’s orders for July 2 involved a massive frontal assault on the centre of the Union line, preceded by an artillery barrage that was to obliterate the northern guns. This plan caused dismay among the generals called upon to carry it out. James Longstreet, the corps commander, told Lee that the charge was doomed to fail: “I have been a soldier all my life. I have commanded companies, I have commanded regiments. I have commanded divisions. And I have commanded even more. But there are no fifteen thousand men in the world that can go across that ground.” Lee insisted it be carried out but Longstreet proved correct. The Confederate artillery did little to silence the northern guns and the grey-clad lines, 12,500 men stretching a mile wide, led by Generals Pickett, Pettigrew, and Trimble, suffered horrible casualties as they moved toward the low stone wall on Cemetery Ridge that was their target. Few made it that far. The charge evaporated into confusion and retreat.

The next day Lee began his retreat back to the South.