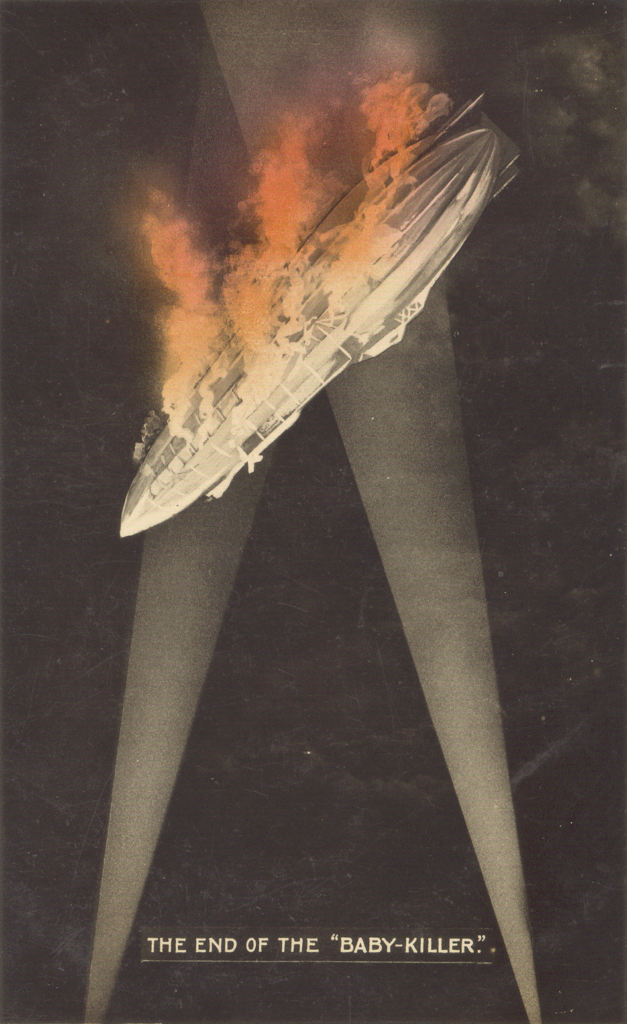

The first Zeppelin raid on Britain

A morale-boosting British poster of World War I

The German Empire had a bad reputation for ruthlessness before it entered World War I in 1914. Kaiser Wilhelm II had urged German troops dispatched to quell the Boxer Rebellion in China to behave as the Huns had 1500 years earlier and German colonialism in Africa was marked by atrocities amounting to genocide. During World War I that nation won an even worse name by its treatment of Belgian civilians and by pioneering new and nasty methods of warfare.

The first of these deadly innovations was aerial bombardment of enemy cities. Air raids on Antwerp and Paris began in the early months of the war and, though these were primitive and ineffectual, they marked a willingness to kill civilians in order to weaken Allied resolve. They were also violations of the Hague convention on the rules of war which forbade the shelling of undefended towns.

On the night of January 19, 1915 the first attack by airships was made on Great Britain. The Kaiser had initially banned bombing London because of the presence of his royal cousins, so the dirigibles dropped their loads on the seaside towns of Great Yarmouth, Sheringham, and King’s Lynn, killing four and wounding 16. Later imperial orders allowed Zeppelins to attack the capital.

These raids shocked the civilized world; the 500 deaths the balloons caused over the course of the whole war seemed somehow more horrid than the loss of 10,000 soldiers in a single afternoon on the Somme. For Germans, however, it was the subject of a merry song:

Zeppelin, flieg, Fly Zeppelin,

Hilf uns in Krieg, Help us in war,

Fliege nach England, Fly to England,

England wird abgebrannt, England will burn,

Zeppelin, flieg! Fly Zeppelin!

Other military novelties pioneered by the Germans included the use of poison gas and unrestricted submarine warfare which resulted in the sinking of the unarmed liner Lusitania, which had sailed from New York, off the coast of Ireland killing 1,198 civilians. All three of these moves occurred within weeks of each other in 1915 and changed the shape of war, for the worse, for ever.

Though the world protested these atrocities — anti-German rioting in Victoria B.C. was so bad that the city had to be placed under martial law — the Kaiser was delighted when von Falkenhayn told him the results of the first poison gas attack. He embraced the general three times and promised pink champagne.