1964

A step toward the end of the Great Schism.

When the Roman empire in the west fell to Germanic barbarians in the 400s, the Christian church was still largely a single body of belief and administration. However, over the next 600 years, eastern and western Christianity grew farther apart, separating slowly on issues of doctrine and politics. The two sides disagreed on whether clergy should marry, the date of Easter, the type of bread used at the Eucharist, whether the Holy Spirit proceeded from God the Father or the Father and Son and how the sign of the cross was to be made. The western church spoke Latin and conducted its services in that language; the easterners spoke Greek but allowed local languages to be used in church. The west looked for leadership to the Bishop of Rome and the German emperor; the east had the Patriarch of Constantinople and the Byzantine emperor.

In 1054, the papal delegate to the east laid a bill of excommunication on the altar of Hagia Sophia while the Patriarch countered by excommunicating the westerners. Though these decrees were meant to be aimed at particular people and as short-term maneuvers, historians date this as the beginning of the Great Schism, a division between a Catholic and an Orthodox Church. Numerous attempts were made during the Middle Ages to reconcile the two sides but as the Byzantine empire was fading in strength these attempts usually took the form of demanding that the eastern church surrender to the pope’s authority. In 1453 when Islam overwhelmed Constantinople and last remnants of the eastern empire were extinguished, the cry in the Orthodox camp was still “better a turban than a tiara” (better to have Muslim rule than papal domination).

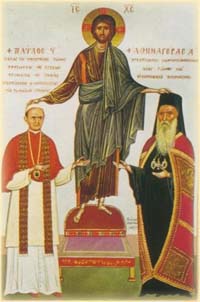

In 1964 Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenogoras I simultaneously read a message of reconciliation in Rome and Constantinople (called Istanbul by the Turks). The two apologized for hostile words by both sides over the centuries, voided the excommunications, and wished for a new era of cooperation, hoping

that this act will be pleasing to God, who is prompt to pardon us when we pardon each other. They hope that the whole Christian world, especially the entire Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church will appreciate this gesture as an expression of a sincere desire shared in common for reconciliation, and as an invitation to follow out in a spirit of trust, esteem and mutual charity the dialogue which, with Gods help, will lead to living together again, for the greater good of souls and the coming of the kingdom of God, in that full communion of faith, fraternal accord and sacramental life which existed among them during the first thousand years of the life of the Church.