Estonian Christmas is a fascinating blend of Orthodox, Lutheran and pagan elements with influences from Scandinavia, North America and Russia also playing their part. It was a holiday that was banned, along with many other religious observances, during the era of post-war Soviet domination — as in the USSR, New Year was promoted as the replacement winter holiday. Since 1989 and the collapse of the Iron Curtain Estonians have been rediscovering Christmas and reformulating it according to their new circumstances.

Like their Nordic cousins Estonians mark the approach of Christmas with Advent calendars and the lighting of Advent candles. Children believe that if they place their shoes out on the window sill during the month of December the elves will fill them with little treats. Though baking, cleaning and shopping will occupy much of Advent, the official beginning of the Christmas season occurs on December 21, St Thomas’s Day, when in the Middle Ages it was customary for work to cease for the holiday. One recent Scandinavian import has been the Christmas office party, or “little Christmas”.

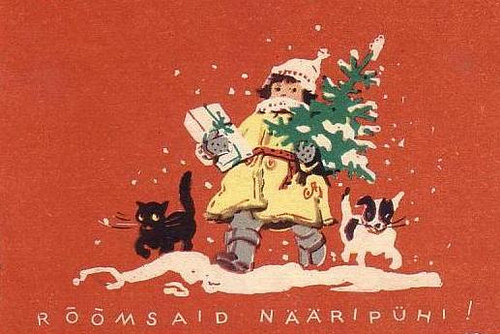

Though some say that the Christmas tree is a German import which became popular only in the nineteenth century, others say that the custom has a longer history. According to some the earliest record of an evergreen tree being used in conjunction with Christmas was in Tallinn, Estonia in 1441. Whatever the truth of the matter there is no doubt that the tree, almost always a fir, is a big part of Christmas today in most Estonian homes. Those who live in the country make it a family practice to go into the woods and harvest the tree themselves. Commercial decorations, folk art and candles are traditional ways to adorn the tree.

On Christmas Eve the president of Estonia follows a 350 year old tradition and declares a Christmas Peace. That evening Estonians, having made all the preparations for the evening meal, traditionally head for the sauna to be steamed clean. After that they step into new clothes and attend church. After the service it is time for dinner. Though turkey has become popular of late many families retain an older menu: roast pork or goose with sauerkraut and blood sausage. For dessert there is a special Christmas bread and ginger cookies. Some families leave the remains of the Christmas meal on the table until the next morning for the spirits of the family dead who will visit the home for Christmas Eve.

Estonians have adopted the Finnish vision of the gift-bringer, a Santa Claus figure who lives in Lappland and who travels by reindeer-drawn sleigh. Once the gifts are delivered Estonians gather about the tree and have to earn the right to open them by performing a song or reciting a poem. Other Christmas Eve activities might include a fireworks display or visiting the graves of family members and lighting a candle — an activity that was a tacit anti-communist, pro-Christian demonstration in the days of Soviet occupation.

Since independence Christmas Day is once again a holiday and is generally spent at home. December 26 is a little more active and involves visiting family and friends. The Christmas season ends on Epiphany and most folk will have taken their tree down by January 6 unless they are of the Orthodox persuasion in which case they are celebrating Christmas Eve and still have more festive days to look forward to