The birthday of two great musicians:

1904 George Formby

The first great British film comedian was born blind to the family of a successful music hall performer. He recovered his sight but never learned to read or write. He wished to follow his father on the stage but his family decreed that “one fool was enough” so he became an apprentice jockey, aided by his very small frame.After his father’s death in 1925, his mother allowed him to pursue a career in the footlights, which he did by imitating his father’s routines — not very successfully as he was often booed off the stage.

Two things changed his future: he took up playing the ukulele and married the very forceful Beryl Ingham, a clogdancer who became his manager. Under her guidance Formby became the premiere music hall act of his generation, making movies and records between his lucrative tours. His greatest hit was “When I’m Cleaning Windows”, a racy little number banned by the BBC. He died in 1961.

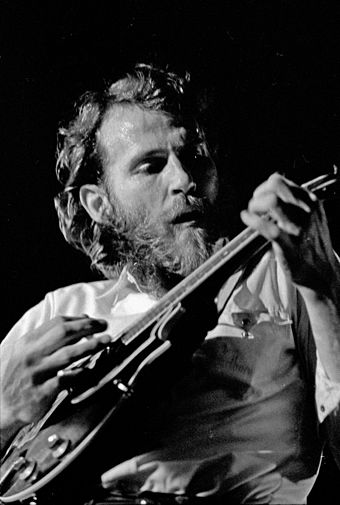

1940 Levon Helm

Raised in Turkey Scratch, Arkansas, Levon Helm wanted to be a musician from an early age. By the time he was in high school his drumming was of professional caliber. He joined rockabilly star Ronnie Hawkins in Canada where he was an important part of The Hawks with Robbie Robertson and Rick Danko. After leaving Hawkins, the group backed up Bob Dylan in his new electric phase and became known as The Band, famous for “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down”, “The Weight” and “Up on Cripple Creek”. After success in Hollywood, solo performances and tours, Helm lost his voice for time in 1990 after a bout with throat cancer but regained to resume his career. His died of cancer in 2012.

Here is a tribute to him by the great Marc Cohn: