1096 The End of the People’s Crusade

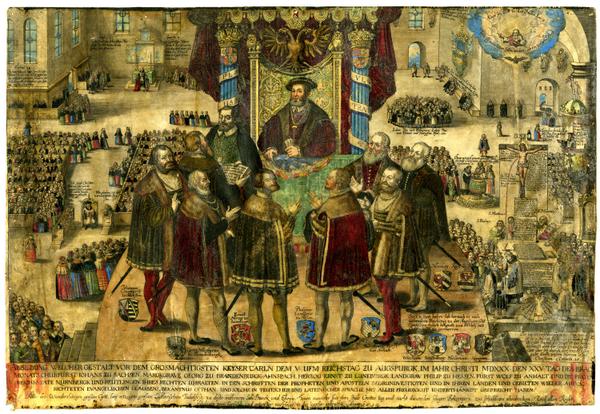

In 1095, Pope Urban II summoned the princes of Europe to form an army to journey to the eastern Mediterranean and do battle with Islamic armies threatening the Byzantine Empire and occupying the Holy Land. Thousands of nobles and knights heeded the call and took part in what is known as The First Crusade or the Princes’ Crusade. At the same, millennial crazes were obsessing the common people of western Christendom who felt that they too had a part to play in liberating Jerusalem. Listening to itinerant preachers such as Peter the Hermit, tens of thousands of ordinary folk, peasants, soldiers, minor nobility, men women and children formed into columns and set out for Constantinople.

On the way, the People’s Crusade proved to be an ungodly menace. They perpetrated anti-Semtic massacres in the Rhineland, extorted food and supplies from the towns they passed through and attacked Byzantine garrisons who were astonished at the arrival of these motley forces. In August 1096 perhaps as many as 30,000 of these folk, drawn from Germany, Italy and France, reached Constantinople. Emperor Alexius, who had no wish to see them linger and become a worse nuisance, arranged to have them ferried across to Asia Minor, which was largely in the hands of Turks. He cautioned them not to take on Muslim armies themselves but to await the arrival of the heavily-armed knights of the First Crusade.

Once in enemy territory the People’s Crusade broke up into quarrelling factions, some reluctant to advance further, some anxious to start the battles they had journeyed so long to fight. While Peter the Hermit was returning to Constantinople to arrange for more supplies the poorly-armed crusaders engaged in several battles and were routed by Turkish forces, particularly at the Battle of Civetot which turned into a massacre. Only a few thousand made it back to the safety of the Byzantine lines; fewer still would survive the rigours of the remaning campaigns and see victory at Jerusalem in 1099.