St Christina the Astonishing

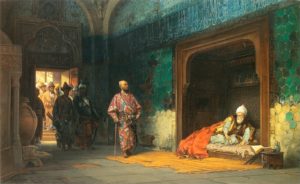

Saints’ lives don’t come much weirder than that of Christina (c.1150–1224), a Belgian woman of low birth. In her early twenties she suffered a seizure that appeared to cause her death. Lying in her coffin in church, she astonished the congregation by levitating to the ceiling, apparently repelled by the stench of sin on her friends and neighbours. She claimed that in her coma she had received a vision of the terrors of Purgatory and was then transported to the presence of God. In her words:

The angels then transported me into Heaven, even to the throne of the Divine Majesty. The Lord regarded me with a favourable eye, and I experienced an extreme joy, because I thought to obtain the grace of dwelling eternally with Him. But my Heavenly Father, seeing what passed in my heart, said to me these words: “Assuredly, my dear daughter, you will one day be with Me. Now, however, I allow you to choose, either to remain with Me henceforth from this time, or to return again to earth to accomplish a mission of charity and suffering. In order to deliver from the flames of Purgatory those souls which have inspired you with so much compassion, you shall suffer for them upon earth; you shall endure great torments, without, however, dying from their effects. And not only will you relieve the departed, but the example which you will give to the living, and your life of continual suffering, will lead sinners to be converted and to expiate their crimes. After having ended this new life, you shall return here laden with merits.”

Back on earth she lived a long life of extreme penance and self-denial, occasionally throwing herself into fires and emerging unscathed or plunging into freezing rivers for long periods. Those around her could not tell if she were mad or blessed and she was imprisoned on more than one occasion. Witnesses, and there were many of them, testified to the miracles she performed and the attention she drew to the plight of souls in Purgatory. She is the patron saint of millers, those suffering from mental illness and mental health workers.