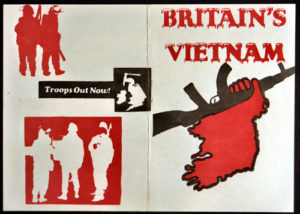

Despite being murderous, terrorist swine, the Irish Republican Army liked to propagandize with cards at Christmas time

Here’s a message of love and peace from 1976:

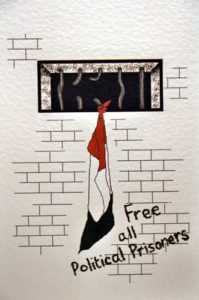

And one from 1996:

Despite being murderous, terrorist swine, the Irish Republican Army liked to propagandize with cards at Christmas time

Here’s a message of love and peace from 1976:

And one from 1996:

Eel is a traditional food for Christmas Eve in Venice. Grilled eels are popular and it is said that the Doge Andrea Gritti died at the age of 84 on December 28, 1538 after eating too many grilled eels on Christmas Eve.

A famous preparation for Christmas Eve on the island of Burano in the Venetian lagoon is a risi e fasjoi col brodo de gò, rice and beans with a broth made of goby. This isn’t the only famous Venetian dish with eel. Risotto de la “Visilia” is a special risotto made on Christmas Eve. It is unusual for two reasons: it is not cooked according to the risotto method, although it’s called a risotto, and it combines cheese with fish. The dish probably evolved from a simple fish pilaf, using, for example, goby. Then the eel was added and finally the beans.

The popularity of eel for Christmas in Naples, and in fact throughout Italy, seems to be a phenomenon of pre-Christian times related to a water cult of the Etruscans that has now become a ritual food in which, in the words of author Carol Field, “the sacred and profane meet.” Of course, one reason that so much Christmas food revolves around fish is because of the symbology of fish in Christological thought, namely, Christ as a fisher of men.

Thanks to http://www.cliffordawright.com/caw/food/entries/display.php/id/51/

He’s a fool that marries at Yule/ For when the corn’s to sheer/ The bairn’s to bear…

December weddings produce inconvenient pregnancies — when there is agricultural work to be done, the woman is out of action. June weddings produce women recovered from childbirth and ready to work in the fields.

Let that be a lesson to you.

The creation of nativity scenes is an ancient and global phenomenon. Some, like those made for Neapolitan royalty in the 18th century, are gorgeous; others are imaginative but not always in good taste. We will feature some of those over the next week.

Depicting the Holy Family as animals in apparently in vogue. Here they are as dogs, ducks, and cats.

“Broncho Billy and the Baby” was a short Christmas allegory by Peter B. Kayne which appeared in The Saturday Evening Post in 1910 and which spawned seven motion pictures. The story is of three bandits who rob the bank at New Jerusalem and head out into the desert to escape. There they encounter a dying woman who extracts a promise from them that they will save her new-born baby. The outlaws battle thirst and the elements and finally one of them makes it back to New Jerusalem with the infant just in time for the Christmas Eve service.

The first cinematic version appeared in 1911, a one-reeler called The Outlaw and the Child; it was followed by three more silent films in 1913, 1916 and 1919. The first sound version (and Universal Studio’s first outdoor talkie) was Hell’s Heroes in 1930, filmed by William Wyler in the Mojave Desert. Charles Bickford, Raymond Hatton, and Fred Kohler Sr play three genuinely hard men and the movie is uncompromising and harsh. Two more sentimental renditions both called Three Godfathers appeared in 1936 and, more memorably, in 1948. The latter was a John Ford western starring John Wayne, Harry Carey Jr. and Pedro Armendariz; it was the only one to dare a happy ending. In 1974 the made-for-television The Godchild moved the plot to three Civil War escapees played by Jack Palance, Jack Warden and Keith Carradine.