Like many Latin American countries Panama celebrates its Christmas with a mixture of traditions from its Spanish Catholic heritage and the influence of the United States; the latter is particularly acute because of the long American occupation of the Panama Canal Zone which ended only in 1999.

In Panamanian homes, for example, the family Nativity scene, always important to Catholic families, will share space with that northern import the Christmas tree. For many years the country had to import tens of thousands of evergreens from the United States — they would arrive in mi-December on ships — but now Panama has its own tree-farming industry and they are much more wide spread. The mix of cultures can also be heard in the Christmas music broadcast by radio and television: traditional songs, the Spanish-influenced “villancicos” and “gaitas”, coexist with American English-language carols.

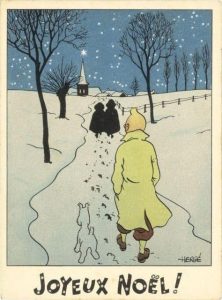

The approach of Christmas is marked by novenas, nine days of religious services involving special Christmas prayers, songs and devotions which take place both in churches and homes, and posadas (above) which reenact the search of the Holy Family for lodgings. It is also a time of parties, little treats from godparents to godchildren, Christmas markets, home decoration and parades. The climax is Christmas Eve with its family dinner: on the menu is sure to be tamales — cornmeal stuffed with chicken, onions and sauce and wrapped in plantain — beans, Arroz con Pollo — chicken and rice — and seafood, especially shrimp. To drink there is rum punch, piña colada, wine and beer with soft drinks for the kids. For Catholic families the Misa de Gallo, the midnight “rooster” mass, is not to be missed.

Influenced by the American example many Panamanian children now expect to find presents under the tree on Christmas, brought either by Santa Claus or the Christ Child. In other families children will have to wait until the more traditional Epiphany date. Then on Dia de los Reyes, Kings’ Day, the Magi will bring gifts and the Christmas season will come to an end with another round of parties.