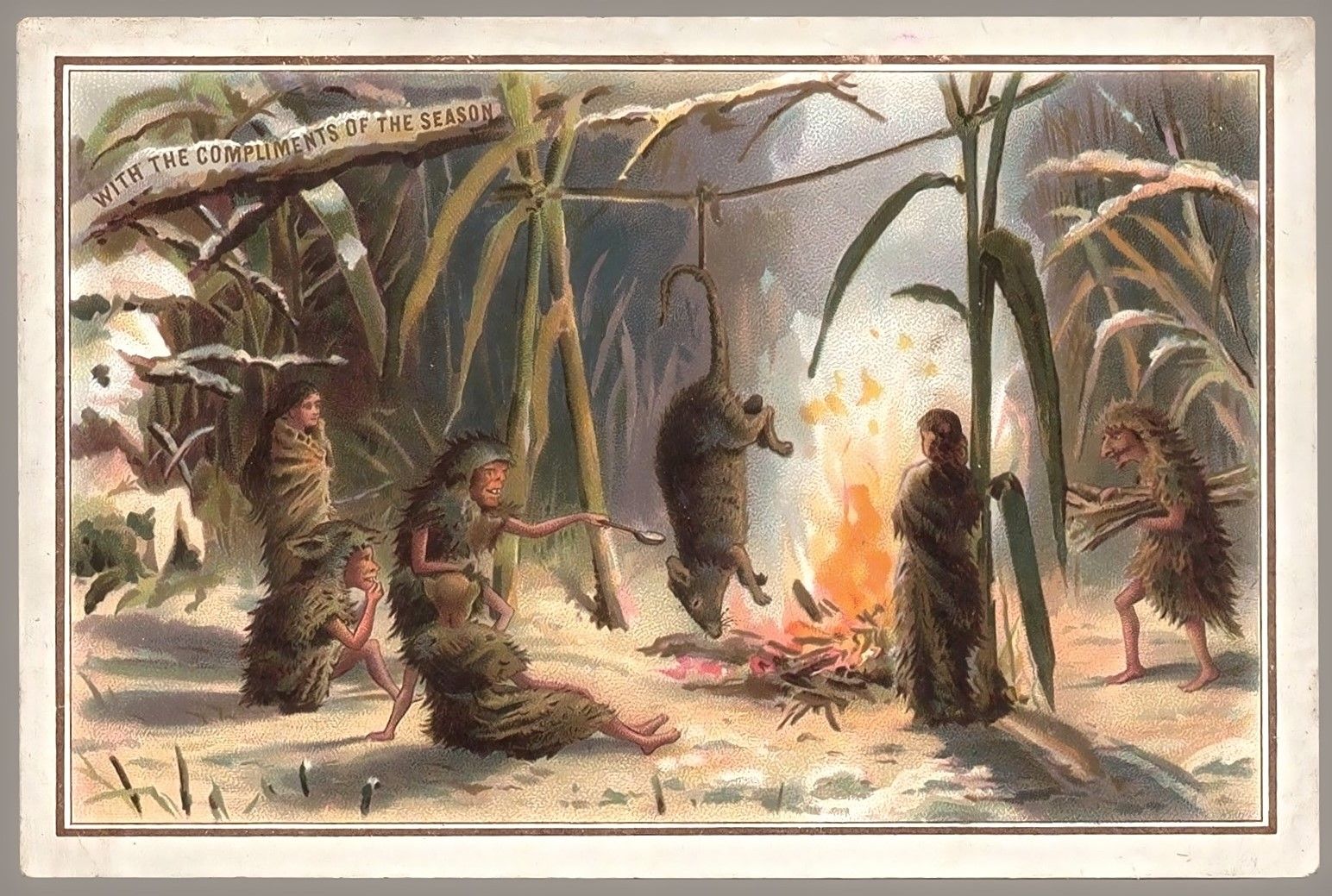

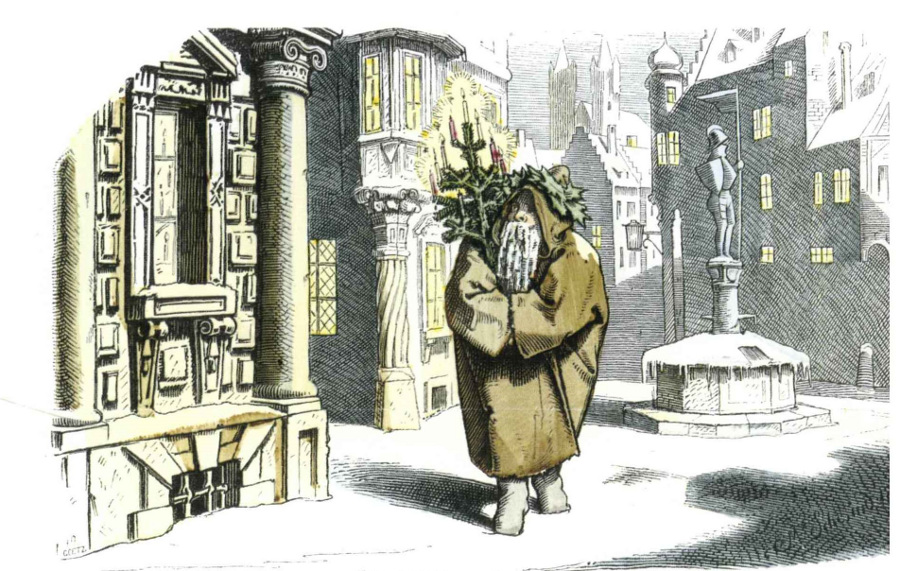

The day before Christmas, known variously as the Vigil of Our Lord, Noche Buena (“The Good Night” in Spanish), Wigilia in Poland, Heilig Abend in Germany, Stedry´vecer (“Generous Evening”) in Slovakia, etc. In eastern Europe it is marked by meatless meals (Advent being a fasting period) and in other countries the occasion of heavy feasting and drinking. In Catholic lands many faithful stay up for the midnight mass and in most places children find it hard to sleep because of their anticipation of the arrival of Santa Claus or another gift-bringer. In Provence Christmas Eve is the Day of Reconciliation when one goes to neighbours to beg or offer forgivenes for wrong-doings during the past year.

It is the most supernaturally powerful of the Twelve Days of Christmas. Animals speak or kneel in homage to the birth of Jesus, bees sing a psalm , etc. In Russia and France it was believed that water turned to wine at midnight while on the isle of Sark this was the time water turned to blood. It was a time for treasure to be revealed, for the Star of Bethelehem to be seen in the Well of the Magi and to remember the dead, for on Christmas Eve spirits will revisit houses where a place is left for them at the table, or a bed, or a bath.