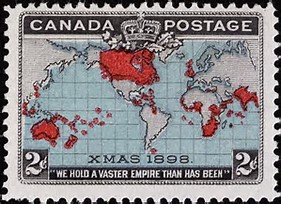

As befits a wintry nation, Canada has given the world a number of Christmas innovations, such as the world’s first Santa Claus parade, put on by the Eaton’s department store. That retail chain is also responsible for a mid-20th century toy craze.

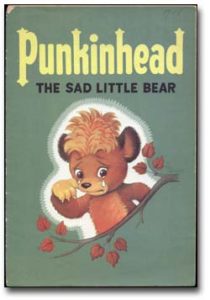

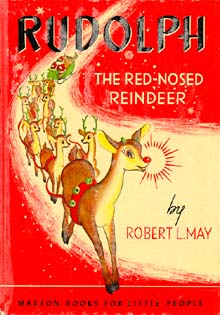

Inspired by the success of Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer as an advertising tool for the Montgomery Ward department stores, the Canadian retailer Eaton’s was moved to develop its own Christmas creature, Punkinhead the Sad Little Bear, who became one of Santa’s helpers. Punkinhead, with his distinctive orange hair, appeared first in Eaton’s 1948 Christmas parade and for the next decade could be found in a series of 13 promotional books and on many items such as pyjamas, records, children’s furniture and toys. He was also popular with Canadian children in the form of a teddy-bear.

Punkinhead was the creation of animation legend Charlie Thorson (1890-1966) of Winnipeg, who had helped develop Snow White for Walt Disney, Bugs Bunny for Warner Brothers, and Elmer the Safety Elephant for the Toronto police department.