1517 The Protestant Reformation begins

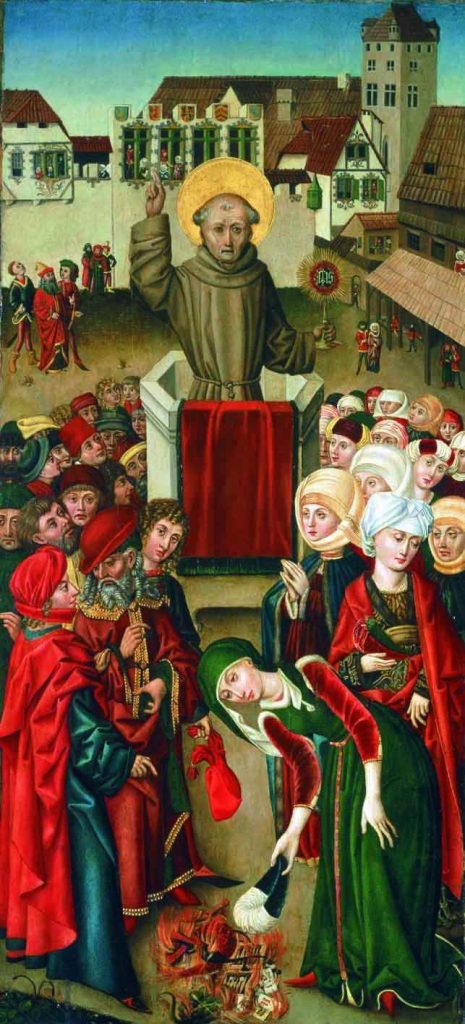

There has never been a period in the history of the Christian Church when someone has not styled himself a reformer and called for changes to practice or doctrine, but no era in this regard was as dynamic, awful, and contentious as the sixteenth century. For centuries, believers inside the Western Church had criticized the wealth of the clergy; the sexual incontinence and ignorance of monks and priests; the belief in transubstantiation, indulgences, papal monarchy or Purgatory. Reformers had come and gone — some to sainthood, some to the stake — but the Church had endured. On October 31, 1517 another critic would step forward and nothing would ever be the same.

Martin Luther (1483-1546) was a German monk of the Augustinian order and a professor of theology at the University of Wittenberg in Saxony. Like many good Catholic thinkers, he had struggled with the notion that the sufferings of those undergoing the pains of Purgatory could be alleviated by the purchase of an indulgence which promised to remit temporal punishment. When Johann Tetzel, a Dominican monk, conducted an indulgence sales drive (in part to finance the building of St Peter’s Basilica) and seemed to promise remission for sins that were yet to be committed, Luther became angry enough to compose a provocative rejoinder. His “95 Theses” were a series of possible discussion points on the topic of Purgatory which he posted on door of All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg, a standard practice alerting students to a debate. (Some historians doubt this dramatic scene. They are wrong.)

Many of these theses were quite barbed, going to the heart of long-time papal claims:

Those preachers of indulgences are in error, who say that by the pope’s indulgences a man is freed from every penalty, and saved.

Every truly repentant Christian has a right to full remission of penalty and guilt, even without letters of pardon.

Christians are to be taught that the pope, in granting pardons, needs, and therefore desires, their devout prayer for him more than the money they bring.

Christians are to be taught that the pope’s pardons are useful, if they do not put their trust in them; but altogether harmful, if through them they lose their fear of God.

Christians are to be taught that if the pope knew the exactions of the pardon-preachers, he would rather that St. Peter’s church should go to ashes, than that it should be built up with the skin, flesh and bones of his sheep.

Why does not the pope empty purgatory, for the sake of holy love and of the dire need of the souls that are there, if he redeems an infinite number of souls for the sake of miserable money with which to build a Church?

These questions were soon printed and spread throughout Germany, creating a theological stir. The Church’s official reply and Luther’s rejoinders quickly changed what was an unremarkable college debate into a crisis for western Christendom. Within a few years, a series of genuine revolutionary movements had begun.