A little askew after its 7,350 km journey from Poland.

Author: gerryadmin

Three Odd NativitY Scenes

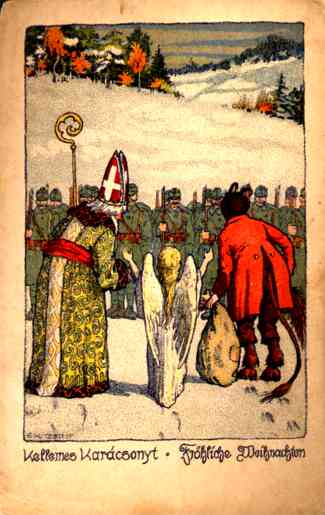

Some Interesting Christmas Cards

You’re not going to see many cards like this. It’s from World War I and features St Nicholas, the Christ Child, and Krampus greeting troops of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Here’s a rather grim American card from World War II in which Hitler, Mussolini, and Tojo are hanged from a gallows while military equipment decorates the tree.

The Szopka

The tradition of making “Szopka Krakowska,” also known as the Krakow Nativity Play, is a cherished and vibrant cultural heritage deeply rooted in the heart of Krakow, Poland. Dating back to the early 19th century, this unique folk art form blends elements of religion, history, and creativity into an exquisite and colorful spectacle. Szopka makers, often referred to as “Szopkarze,” meticulously craft miniature nativity scenes within ornate wooden or cardboard structures, using a wide range of materials like colored paper, foil, and decorative ornaments. These miniature masterpieces not only depict the holy nativity scene but also incorporate iconic landmarks of Krakow, showcasing the city’s rich history and architecture. Every year, on the first Thursday of December, the Szopka Parade and Competition takes place in the Main Square of Krakow, where these beautifully crafted works of art are proudly displayed and judged. The tradition of Szopka Krakowska not only celebrates the Christmas story but also serves as a testament to the creativity and craftsmanship of the people of Krakow, preserving their cultural identity for generations to come.

Christmas in Constantinople 1899

At the turn of the 20th century Constantinople (which had not yet become Istanbul) was a multicultural metropolis with a large Christian population drawn from the Ottoman Empire’s conquered minorities. Here is the account of Isabelle Bliss Trowbridge, a young woman working for an American missionary society.

We read so much these days about Constantinople as the seat of Turkish misrule and the scene of great tragedies during the past year that it may be hard to think of it under its own beautiful name of “Dère-e-Saadet” or the “Gate of Felicity,” and to realize that there, too, Christmas is celebrated by thousands of people every year.

We read so much these days about Constantinople as the seat of Turkish misrule and the scene of great tragedies during the past year that it may be hard to think of it under its own beautiful name of “Dère-e-Saadet” or the “Gate of Felicity,” and to realize that there, too, Christmas is celebrated by thousands of people every year.

We speak of Christmas time in Turkey rather than of Christmas Day, for three different dates are kept by the various churches. Christmas extends from the twenty fifth of December to the twenty first of January. The Protestants and Catholics, including, of course, most of the foreign residents, celebrate the twenty fifth of December. The followers of the Greek Church, that is to say, Greeks, Russians, and Bulgarians, cling to the Old Style calendar, so that according to their reckoning Christmas falls on our sixth of January. The Armenians hold to the reckoning of the Gregorian Church and keep the sixth of January, Old Style, or our nineteenth. Between these dates fall both the new and old New Years’ days. As almost every great festival is observed for three consecutive days by the eastern churches it follows that for about a month there is scarcely a day without some special celebration.

American College faculties may consider the question of the length of the Thanksgiving vacation, but they find it an easy problem in comparison with that which confronts principals of schools in Constantinople, who try in vain to arrange the holidays so as to satisfy all nationalities. The first Christmas is observed much as it is in this country. The American and English boys tramp through the woods in the valley of the “Sweet Waters” searching for the mistletoe. The children hang up their stockings and the mothers make plum puddings.

In a native home it is quite different. Let us go to an Armenian house near by and see what we can of the celebrations. It is late Christmas eve. We knock at the street gate, which is mysteriously opened by an invisible cord. We cross the marble court, crusted to-night with a thin layer of snow, and enter the house door. The room is a high one, with bare walls and long windows. Several handsome rugs cover the floor. A long divan across one end of the room, and two or three stiffly upholstered chairs make up the furniture. The family is seated on the floor around an open brazier of red hot coals. We are given the seat of honor on the divan and treated to many courses of sweets, nuts, and black coffee. Our conversation is continually interrupted by strange noises in the street. We lean from the overhanging window to watch the troops of masqueraders who parade the streets with colored lanterns and drums, and make night horrible with their drunken shouts, refusing to go away without some reward for the entertainment they have afforded.

These noises continue during a greater part of the night. About four o’clock in the morning the church bells begin to ring, not merry Christmas chimes but harsh clanging sounds like the bell on a locomotive. We peer again from the window. A few early risers are groping their way along the dark street toward the church where service has already begun. We all soon follow them into the cold, dimly lighted church. Many worshippers are there before us, kneeling on the marble pavement in front of the gaudy pictures of the Virgin; a purple-capped, black-robed priest is monotonously mumbling the prayers in an ancient tongue and, at the same time, the chorus boys are chanting in unnatural tones to the accompaniment of clashing cymbals. We leave whenever we like and return to the feasting at the house. The day, as also the two following it, is spent in visiting and banqueting, varied by attendance at church in all the gaudy attire which can be procured.

Foreign influence has of late years introduced many new customs in regard to the celebration of Christmas. The children of the mission schools are taught to sing carols and are often afforded the delight of a Christmas tree loaded with good things. The exchange of presents is becoming more general, and among the classes who try to imitate the French, the custom frequently prevails of giving balls and soirées on Christmas night.

Christmas Chuckles

Get Ready for Christmas

Pope Leo and the Nativity

Leo was Bishop of Rome from 440 to 461. He is the only pope, aside from St Gregory, to be called the Great. He was an able administrator, diplomat, and preacher – among the many sermons of his that have survived are several that deal with the theology of Christmas. Here are some excerpts from these orations.

Let us be glad in the Lord, dearly beloved, and make merry with spiritual joy. For there has dawned for us the day of new redemption, of ancient preparation, and of eternal bliss. In this annual feast there is renewed for us the sacrament of our salvation, which was promised from the beginning, was accomplished in the fulness of time, and will endure for all eternity. (Homily 2,1.)

Let us be glad in the Lord, dearly beloved, and make merry with spiritual joy. For there has dawned for us the day of new redemption, of ancient preparation, and of eternal bliss. In this annual feast there is renewed for us the sacrament of our salvation, which was promised from the beginning, was accomplished in the fulness of time, and will endure for all eternity. (Homily 2,1.)

In assuming our nature, Christ became for us a ladder, so that through Him we can now ascend even unto Himself. (Homily 5,3.)

Let Catholic faith recognize the glory of the Lord in His humility; and let the Church, which is the body of Christ, exult in the sacraments of her salvation. For unless the Word of God had become flesh and had dwelt amongst us, unless the Creator Himself had descended to enter into communion with His creature and in His birth had restored the old man by a new beginning, death would have reigned from Adam even unto the end (Rom. 5:14), Irrevocable condemnation would have been all men’s lot, and the very fact of birth would have been unto all cause of perdition But He became a man of our race, that we might become partake of the divine nature. The birth that was His from the virginal womb, He made available to us in the baptismal font. He gave to water the same power that He gave to His mother. For the power of the Most High and the overshadowing of the Holy Spirit (Luke 1:35) which made Mary give birth to the Savior, likewise effect that water gives new life to the believer. (Homily 5,5.).

Although the infancy which the majesty of God’s Son did not disdain passed into the maturity of manhood, and although all the acts of humility undertaken for us ceased once the triumph of the passion and resurrection had been attained, yet today’s festival renews for us the sacred infancy of Jesus born of the Virgin Mary; and while we adore the birth of our Savior, we find that we are celebrating too the commencement of our own life. For the birth of Christ is the origin of the Christian race, since the birthday of the Head is the birthday of the body. (Homily 6.2)

Clear Toy Candy

Another Gastro Obscura posting about unique Christmas foods around the world.

In the 18th century, children in Pennsylvania would inevitably find a two-for-one gift in their Christmas stockings. Each piece of clear toy candy, a sweet pioneered by German immigrants, lives up to its name. As the treats were shaped like trains, ships, or animals, children could play with them before eating. Once also called barley candy because some recipes were said to include sweet barley sugar, the candies appeared in the region as early as 1772. Made of colorful, boiled sugar syrup, clear toy candy is carefully made in cold kitchens to preserve its glassy look. Often, the sweets come in Christmas red or green, or the natural yellow of the lightly-caramelized syrup.

In the 18th century, children in Pennsylvania would inevitably find a two-for-one gift in their Christmas stockings. Each piece of clear toy candy, a sweet pioneered by German immigrants, lives up to its name. As the treats were shaped like trains, ships, or animals, children could play with them before eating. Once also called barley candy because some recipes were said to include sweet barley sugar, the candies appeared in the region as early as 1772. Made of colorful, boiled sugar syrup, clear toy candy is carefully made in cold kitchens to preserve its glassy look. Often, the sweets come in Christmas red or green, or the natural yellow of the lightly-caramelized syrup.

These sweets are decidedly vintage, both in shape and in taste (traditional clear-toy candy is unflavored). Collectors gather the molds from long-gone candy companies, and only a few confectioners still make the treats. Nevertheless, they’re still a must for many families celebrating Christmas in Pennsylvania.

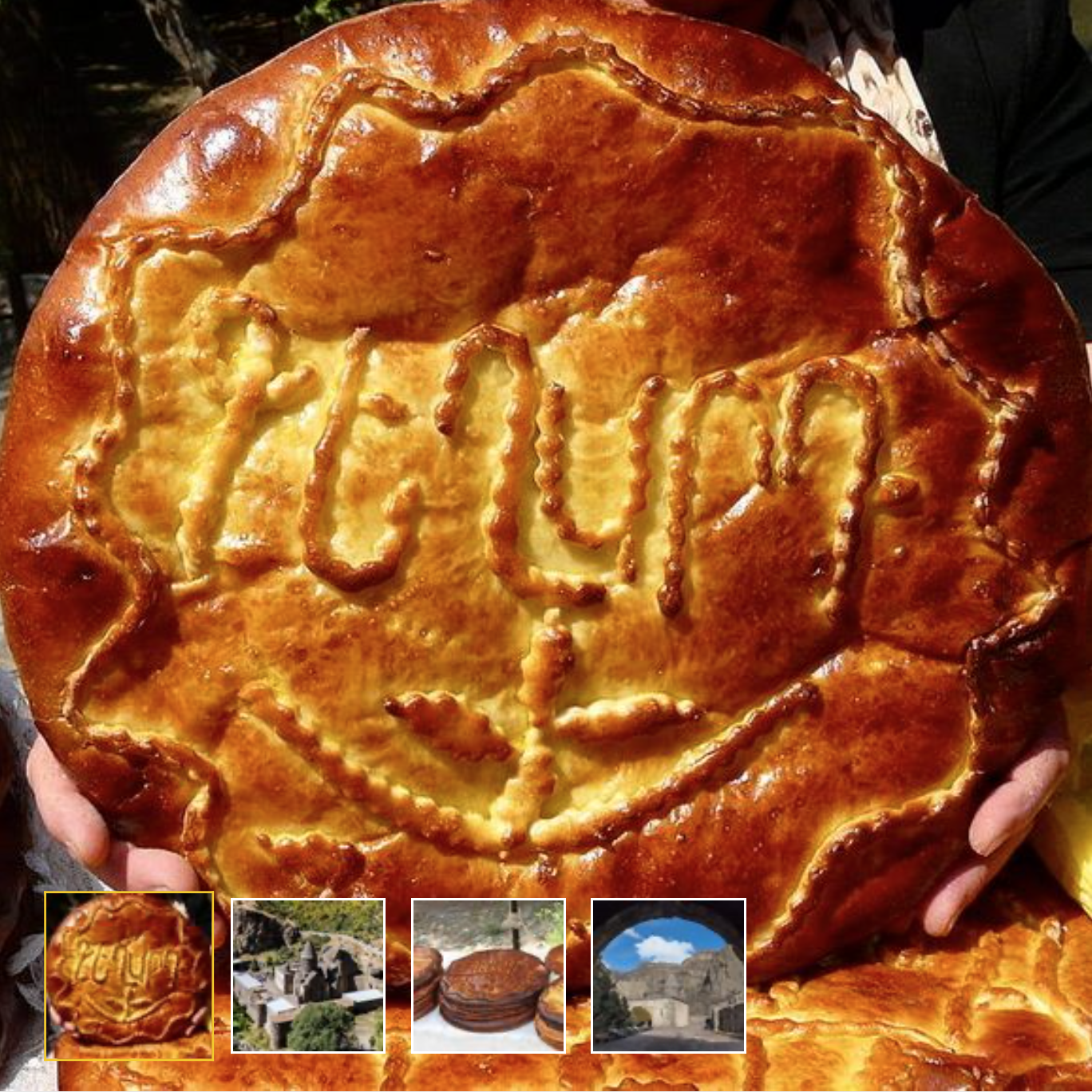

Gata Cakes

More obscure Christmas food from Gastro Obscura. This is one of a small number of treats associated with Candlemas, the end of the Christmas season. In the rugged Upper Azat Valley in Armenia, around the entrance to the rock-carved Geghard Monastery, you’ll notice elderly ladies clustered around roadside stalls leading to the site, selling round Gata cakes inscribed with patterns and intricate Armenian script.

In the rugged Upper Azat Valley in Armenia, around the entrance to the rock-carved Geghard Monastery, you’ll notice elderly ladies clustered around roadside stalls leading to the site, selling round Gata cakes inscribed with patterns and intricate Armenian script.

The glazed pastry has a crusty texture that’s soft once you bite into it, and is stuffed with a sweet filling (khoriz) made from a fluffy mixture of flour, butter, and sugar, with a consistency of baked custard. Though styles will vary between regions and villages —with variants including matsuni (Armenian yogurt), walnuts, or dried fruit in the filling—the most famous version comes from the villages around Geghard and Garni, where locals will decorate these round pastries with tree-like motifs, diamond shapes, hearts, or words (such as “Geghard”).

These delicious cakes, which are actually more like a sweetened kind of bread, have their roots in religious tradition. Armenia adopted Christianity in the fourth century after the religious leader Gregory the Illuminator baptized the royal family. Shortly thereafter, Gregory identified a sacred spring in a cave at Geghard and the first chapel was built inside. In the centuries that followed, monks built more formal structures, including the most prominent chapel in 1215, using rocks from surrounding cliffs.

While it’s unclear when vendors started selling Gata cakes at the site, the treats have been linked to Christian traditions for some time. They’re particularly prevalent during the Christian holiday of Candlemas (Tiarn’ndaraj). According to the Armenian Apostolic Church’s calendar, the celebration occurs 40 days after Christmas and commemorates when the baby Jesus was presented at the temple in Jerusalem. Armenian women knead their love and warmth for their family into the dough, so that each cake bestows peace and success upon their household. In addition to love and flour, a coin is often hidden inside the bread. The person to get the coin will enjoy good luck all year.