For centuries Hungary has been a cultural cross-road; situated between eastern and western Europe and the Balkans, rich in ethnic identity and a land where Protestantism and Catholicism can each claim many followers, Hungary shows its mixed heritage in the celebration of Christmas.

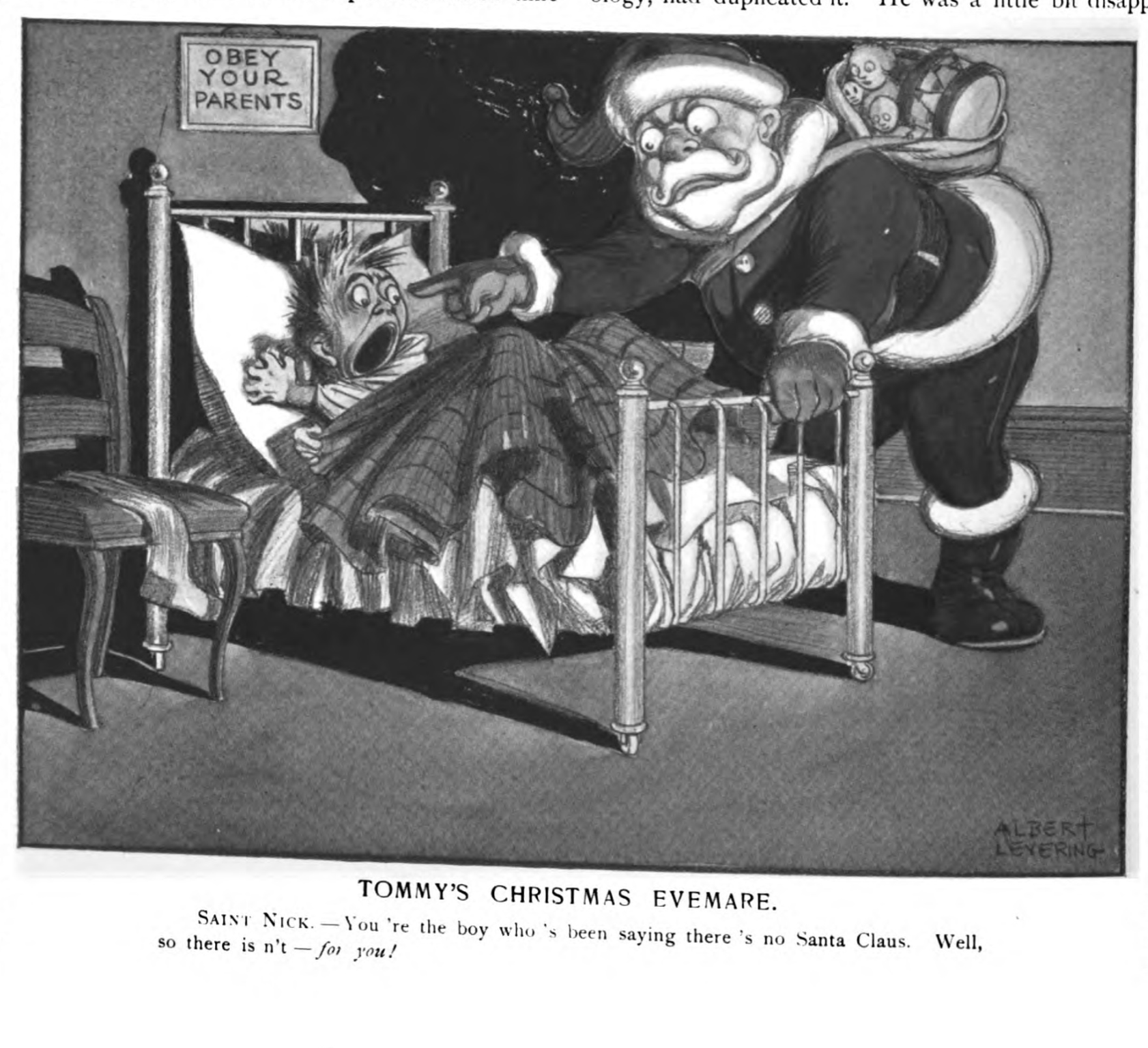

On December 6, St Nicholas Day, the saint (Mikolás to Hungarians) in his traditional bishop’s attire arrives to deliver small presents and candy to good girls and boys and switches to the bad ones. Children leave their neatly-polished shoes out for Nicholas to fill. On his travels to shopping areas and schools and in parades he is often accompanied by an angel and a devilish companion named Krampusz.

But the saint’s appearance is only a prelude to the Christmas celebrations which accelerate on December 24. Adults hurry home from work, children are sent off to play and the tree is decorated in their absence. After a visit from the gift-bringer (which on Christmas Eve is the baby Jesus or his angels) a bell is rung and children may view the tree and open their presents. Following supper the family might sing carols or attend midnight mass. The following two days are national holidays. Christmas itself tends to be reserved for immediate family and the large afternoon dinner, often of turkey; visiting friends and family takes place on December 26.

Seasonal delights include the szalon cukor, brightly wrapped chocolate candies with a marzipan or jelly centre, and baigli, traditional walnut and poppy-seed cakes.