Author: gerryadmin

July 1

1935

The Regina Riot

Canadians are a pretty peaceful folk; it takes a lot to get them upset, and even when they burst into riot or rebellion, it’s usually pretty small potatoes compared to disorders in the rest of the world. Take for example the “Regina Riot.”

In 1935, Canada was in the midst of the Great Depression, with the west of the country particularly hard hit as the economic downturn coincided with a dustbowl drought and a grasshopper plague. Tens of thousands of men were unemployed and living in remote government camps where they were set to useful labour such as building roads for the princely sum of 20 cents a day. By the spring of 1935, labour organizers had convinced many of these men to embark on protests to win a series of ambitious improvements in their pay and conditions. To emphasize these demands 1,000 men left the camps to ride freight cars heading east in what was known as the “On to Ottawa Trek.”

Unwilling to see the national capital invaded by an army of angry workers, Prime Minister R.B. Bennett agreed to meet a delegation of trekkers in Ottawa, on the condition that the remainder of the men go no farther than Regina, Saskatchewan, where the Royal Canadian Mounted Police had a significant presence.

The meeting in Ottawa went very badly with both sides using intemperate language and no settlement reached. Some of the strike leaders were genuine radicals, ex-Wobblies or members of the Canadian Communist Party, which gave Bennett a chance to denigrate them. When the leaders returned to Regina, they held an open-air meeting at Market Square. There they were attacked by truckloads of RCMP. Fighting broke out; as the crowd dispersed, running battles were held in the streets: tear-gas was used, shots were fired, shops were vandalized. After the smoke cleared, two men — a Mountie and a striker — lay dead. The police arrested over 100 people but public sympathy lay with the strikers. An angry Saskatchewan Premier Jimmy Gardiner denounced the federal government (which believed it had crushed a communist conspiracy) for having provoked the ruckus and proposed that the remaining strikers be returned to their homes.

Though the Trek was dispersed, Bennett’s popularity sunk even lower and he was shortly to be voted out of office. Today the “Regina Riot” is the name given to the local women’s football team.

June 28

1914

A dreadful moment

It’s one of those great turning points in history. A young terrorist, disappointed at missing his target earlier in the day, is astonished to see the man appear, being driven slowly toward him again in an open car. He steps forward, aims at the middle-aged couple in the back seat and fires his pistol …

Had Gavrilo Princip missed; had the driver taken the correct route; had the Archduke not insisted on seeing the victims wounded in the previous attack, would Austria and Serbia have fought anyway? Would World War I still have broken out? Would 20,000,000 have died? Would my great-uncle Bill still have suffered shell-shock on the Western Front and wandered away to be lost forever to his family?

The slow collapse of the Turkish Empire meant that it was withdrawing from parts of southeastern Europe it had ruled for centuries, leaving a political vacuum that both the Kingdom of the Serbs and the Austro-Hungarian Empire wished to fill. A particularly contentious area was Bosnia, with its mixed population of Orthodox Serbs, Muslims and Catholic Croats. It was ruled by Austria but coveted by Serbia who wished to build a pan-Slavic state in the region. A teen-age Bosnian Serb, Gavrilo Princip, wished to see his nation join Serbia and associated himself with the Black Hand, a terrorist group linked to the Serbian secret police. When the Black Hand learned that the heir to the Austrian throne, Archduke Ferdinand, would be visiting Sarajevo they saw an excellent opportunity to create an outrage that would lead to a war of liberation. They trained and supplied Princip and five others for a murderous attack on the royal procession.

However, on the day, things did not work out as planned. The first two would-be killers, armed with pistols and bombs, froze as the Archduke and his wife Sophie drove by. Farther on, the third threw his bomb but it bounced off the royal car and exploded on the street injuring 16 people. The bomber atttempted to commit suicide by swallowing a cyanide pill but it was old and had lost its potency – he then leapt into the river but discovered it was only knee-deep. He was arrested and beaten up by the crowd as the motorcade proceeded on. The Archduke reached the safety of the town hall but then insisted on being taken to the hospital to visit those wounded by the bomb. The route — which was the wrong one — took the car to the spot where Princip was standing. He took out his Belgian semi-automatic FN .38 and fired the shots that would start World War I.

Princip was too young to be executed so he was imprisoned and died of tuberculosis in 1918. Three of his co-conspirators were executed and a dozen others involved in the plot were imprisoned. But what of the Serbian masterminds of the plot who were safe inside their borders? In 1916 when secret talks were carried out between Austria and Serbia about a possible peace, the Austrians demanded an end to such plots and the Serbian Regent, who was himself concerned about the power wielded by his military and intelligence agencies, obliged by arresting those who had planned the assassination. Three of his officers were executed on trumped-up charges and others thrown in jail.

Despite the horrific results of Princip’s actions, the killer is still a hero in Serbia. In 2015 that country’s president attended the unveiling of a statue in Belgrade to the terrorist and proclaimed: “Princip was a hero, a symbol of liberation ideas, tyrant-murderer, idea-holder of liberation from slavery, which spanned through Europe”.

June 26

1522

Suleiman the Magnificent attacks the Knights of St John on Rhodes

With the fall of Acre in 1291 the orders of crusading monks, the Knights of St John, the Templars and the Teutonic Knights, would be based in the Holy Land no more. The Teutonic Knights would concentrate on crusading against pagans in northern Europe, the Templars would be destroyed by the papacy and the King of France, and the Knights of St John (aka the Hospitallers) moved temporarily to Cyprus. In 1309 the Knights of St John seized territory from their fellow (albeit Byzantine Orthodox) Christians — the island of Rhodes just off the coast of what is now Turkey and the port of Halicarnassus (now the resort town of Bodrum) on the nearby mainland. The Knights built powerful fortifications in both sites (sadly the ruins of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, were dismantled and used in building towers) and from there they fought against Islamic armies and navies, making themselves a considerable thorn in the side of the powerful Turkish sultanates in the eastern Mediterranean. As such they became the target of Muslim attempts to drive them away. In 1444 the Mameluke Sultan of Egypt mounted an expedition against them. The siege lasted 40 days but with the help of a Burgundian fleet, the Mamelukes were defeated. Mehmet the Conqueror, the Ottoman Turk who took Constantinople in 1453 and destroyed the Byzantine Empire, was determined to take Rhodes but his attempt in 1480 failed.

On June 26, 1522 the newly-crowned Ottoman emperor, Suleiman the Magnificent, arrived off the coast of Rhodes with 400 ships and an army of 100,000 men to attack the 7,000 men defending Rhodes under the Grand-Master, Philippe Villiers de l’Isle-Adam. Over the course of months a steady artillery bombardment and a series of underground mine explosions opened gaps in the walls. On December 22, both sides agreed to an honourable surrender. The Knights would leave Rhodes with their weapons and wealth and as many civilians as wished to accompany them. The Turks promised those Christians who stayed that they could keep their churches and pay no taxes for five years.

The fall of Rhodes tightened the Turkish hold on the Levantine coast but the Knights of St John would resume their war against them after they accepted a new base of operations on the island of Malta, donated by its overlord, the king of Spain. The annual rent for this island would be a single falcon payable on All Saints’ Day.

June 22

1941

Operation Barbarossa

Invading the Russian heartland from the west seems to be a bad idea. The Teutonic Knights tried it and lost the Battle of the Ice in 1242; the Swedes tried it and were thrashed at Poltava in 1709; Napoleon tried it and never recovered from the retreat from Moscow in 1812; and Hitler tried it in 1941 with Operation Barbarossa, the largest military action in world history. The result: close but no cigar.

Adolf Hitler’s political testament My Struggle, written in the 1920s, made his intentions clear. The future of Germany lay in expanding into eastern Europe, cleansing it of its Slavic population, and making living space for a racially-pure Aryan race. We completely break our past colonial and trade policy and deliberately turn to acquiring new lands in Europe. We can only consider Russia and its neighboring countries. After Hitler’s election in 1933, the relations between Germany and the USSR were hostile; the Spanish Civil War was a proxy conflict with both nations pouring arms and men into the opposing sides. Stalin watched in alarm as Hitler swallowed up Austria and Czechoslovakia and turned his eyes on Poland but could not bring himself to ally with other German foes such as Britain and France.

The world was astonished, therefore, to learn that in August 1939, these antagonists had signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which set out a 10-year peace treaty (and which, in secret clauses, vowed cooperation in an invasion of Poland). Scarcely more than a week later, Germany invaded Poland and soon after, Soviet forces occupied the east of the country and would go on to extinguish the independence of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia.

The German Reich and the Soviet Union now shared a long common border. No one expected their peace to last the full 10 years but, despite numerous warnings from spies and western powers, Stalin was taken by surprise when, less than two years after the pact, millions of German troops swarmed into the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa, named for a medieval Holy Roman Emperor. Joined with allies from Finland, Slovakia, Italy, Hungary and Romania, German divisions pressed deep into the USSR, taking millions of Red Army soldiers prisoner. But despite overrunning vast Russian territory and sweeping aside a number of armies, the German did not achieve their goals: the front stalled in front of Leningrad and Moscow as winter set in. A desperate gamble had failed.

June 20

1909

Birth of a romantic legend

Though this daily blog charts history’s more momentous events — battles, treaties, catastrophes, and atrocities — there can still be time to celebrate one who, in the words of Dr Johnson’s praise of David Garrick, added to the “the public stock of harmless pleasure”.

Errol Flynn was born in Tasmania and educated in Australia and England. Expelled from school for having sex with the laundry lady and fired from his first job for theft, he gave early signs of a life spent in ignoring conventional morality. By the age of 24 he had been bitten by the acting bug and started appearing on stage in Britain and in lightweight films. Though dramatic depth was never his strongpoint, his easygoing charm and swashbuckling manner soon saw him starring in roles that featured his lithe form and skill with a blade, such as Captain Blood, The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Charge of the Light Brigade. He was equally at home twirling a six-gun in Dodge City, They Died With Their Boots On, Santa Fe Trail and Virginia City.

Flynn could not resist the bottle or women, especially young (very young) women and scandal dogged his career. He died dissolute and puffy at the age of 50 but will always be remembered for his way with romantic lines that no present-day actor could get away with. Heed the following.

From The Adventures of Don Juan

Don Juan: I have loved you since the beginning of time.

Catherine: But you only met me yesterday…

Don Juan: Why, that was when time began!

Or

Catherine: But you’ve made love to so many women.

Don Juan: Catherine, an artist may paint a thousand canvasses before achieving one work of art, would you deny a lover the same practice?

June 18

Hroswitha of Gandersheim

One way medieval historians make themselves annoying to the general public is by contradicting popularly-held beliefs. After centuries of stating that the fall of Rome produced a Dark Age in the West, medievalists began to say there was no such thing. It’s “late antiquity”, they said, not the Dark Ages, and it wasn’t so horrible after all. The barbarians must no longer be called that; they became “migrants” or “settlers”. They didn’t invade so much as they “intermingled” and “created new societies”. Were these new societies literate? Well, no. Did they encourage long-distance trade or sophisticated mass-production as in the days of the Roman Empire? Sadly, no. Did they have the rule of law? No, savage tribal customs replaced Roman law. So, after twenty years or so of this sort of revisionism a new group of historians began pointing out that the barbarian invasions did, indeed, cause a civilizational catastrophe that took centuries to overcome. Among the things that disappeared in Western Europe was drama and it took a remarkable woman to reintroduce it.

Hroswitha of Gandersheim (c. 935-c. 1002) was a German nun during the cultural renaissance that was sponsored by the German Ottonian emperors in the tenth century. She was probably born into a noble family and certainly received a classical education that was not usually given to women of the time, even of the elite classes. Even more remarkably one of her teachers was herself a woman, the abbess Gerberga, sister of Emperor Otto I and a former Queen of France.

We have no record of anyone in Latin Europe writing a play since the days of imperial Rome but Hroswitha took it upon herself to revive the art form. Her plays deal with political problems, women’s roles, the challenge of sin and romance. She also wrote saints’ lives, poetry and works of history. Unlike many female authors, right up until the twentieth century, Hroswitha did not hide her sex, rather she sought recognition of herself as an exceptional woman, blessed by God.

June 18

1815

The Battle of Waterloo

For twenty years, Napoleon Bonaparte, a minor Corsican noble who had made himself Emperor of the French, had troubled Europe with his armies and insane ambitions. Millions had died in the battles that raged from the Caribbean to the ruins of Moscow, but in 1814 Napoleon had found himself facing a great coalition that had brought him to admit defeat. Instead of taking him behind the woodshed and shooting him, thus ridding the world of such a pest, the crowned heads of Europe decided that it would not do to execute someone who had worn an emperor’s crown, an act that might give the lower orders dangerous ideas. So, a ridiculous fiction was devised, whereby Napoleon would continue his life as a ruler, but his domain would be restricted to the tiny island of Elba, off the west coast of Italy. He was given the freedom of his territory but a British squadron patrolled the island’s shores to prevent his escaping.

But escape he did. A small boat took him to France where the armies that had been sent to arrest him fell under his spell and reinstated him in imperial splendour in Paris. Poor Louis XVIII, whose Bourbon dynasty had been restored, fled quickly to England. For 100 days Napoleon ruled again and gathered a force to smash the coalition, marching north into Belgium to encounter a British army stationed there, before it could be joined by a Prussian contingent.

The leader of the British was Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, who had a splendid career fighting in India and driving the French out of Portugal and Spain. Napoleon derided him as a “sepoy general” but he had beaten every French marshal that Bonaparte had sent against him. The two sides met at Waterloo, south of Brussels, and fought a bloody battle all day. Napoleon’s artillery hammered the British across a valley and senseless cavalry charges by both sides proved that mounted units were the best-looking but stupidest troops on the field. When, in the evening, German reinforcements arrived and the massed fire of British rifles drove back uphill charges by Napoleon’s elite Imperial Guard, the battle was lost. Shouts of “La Garde recule. Sauve qui peut!” (“The Guard retreats. Save yourself if you can!”) prompted a retreat. Napoleon abdicated his throne and surrendered to the British on July 15, 1815.

June 15

1859

The Pig War between Canada and the USA

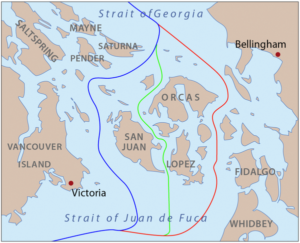

The Oregon Treaty of 1846 had settled the boundary between British North America (later to be Canada) and the United States from the prairies to the Pacific along the 49th parallel. Things got a bit tricky however in the waters between the mainland and Vancouver Island — the Island, occupied by the British, dips below the parallel. Unfortunately, ambiguity in the language of the treaty resulted in rival claims to the San Juan Islands. An online article by Tod Matthews takes up the story:

Before the Pig War, the British were determined to resist the tide of American migration sweeping across the Rocky Mountains. They argued that the Americans were trespassing on land guaranteed to Britain by earlier treaties and explorations and through trading activities of the long-established Hudson’s Bay Company. Americans considered the British presence an affront to their “manifest destiny to overspread the continent” and rejected the idea that the land west of the Rockies should remain under foreign influence. The Oregon Treaty of 1846 gave the United States undisputed possession of the Pacific Northwest south of the 49th parallel, extending the boundary “to the middle of the channel which separates the continent from Vancouver’s Island; and thence southerly through the middle of the said channel, and of Fuca’s straits to the Pacific Ocean.” However, the treaty created additional problems because its wording left unclear who owned San Juan Island. The difficulty arose over that portion of the boundary described as the “middle of the channel” separating British-owned Vancouver Island from the mainland. Actually, there were two channels: Haro Strait (nearest Vancouver Island) and Rosario Strait (nearer the mainland). San Juan Island lay between the two. Britain insisted that the boundary ran through Rosario Strait; the Americans claimed it lay through Haro Strait. Thus, both sides considered San Juan theirs for settlement.

By 1859, there were about 25 American settlers on San Juan Island. They were settled on redemption claims which they expected the U.S. Government to recognize as valid but which the British considered illegal. Neither side recognized the authority of the other. Amazingly, this conflict occurred on an island only 20 miles long and seven miles wide, covering 55 square miles

When American settler Lyman Cutlar shot and killed the Hudson’s Bay Company’s marauding pig, the feud between nation’s came to blows. British authorities threatened to arrest him. American citizens requested military protection. Brig. Gen. William S. Harney, the commander of the Department of Oregon and anti-British to boot, responded by sending a company of the 9th U.S. Infantry under Capt. George E. Pickett to San Juan. James Douglas, governor of the Crown Colony of British Columbia, was angered at the presence of American soldiers on San Juan. He had three British warships under Capt. Geoffrey Hornby sent to dislodge Pickett but with instructions to avoid an armed clash if possible. By August 1861, five British warships mounting 167 guns and carrying 2,140 troops opposed 461 Americans, protected by an earthen redoubt and 14 cannons. When word of the crisis reached Washington, officials there were shocked that the simple action of an irate farmer had grown into an explosive international incident. San Juan Island remained under joint military occupation for the next 12 years. In 1871, when Great Britain and the United States signed the Treaty of Washington, the San Juan question was referred to Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany for settlement. On October 21, 1872, the emperor ruled in favor of the United States, establishing the boundary line through Haro Strait. Thus San Juan became an American possession and the final boundary between Canada and the United States was set. On November 25, 1872, the Royal Marines withdrew from English Camp. By July 1874 the last of the U.S. troops had left American Camp. Peace had finally come to the 49th parallel.

June 14

Saint Joseph the Hymnographer, “the sweet-voiced nightingale of the Church”

Sicily in the 9th century was ruled by the Byzantine empire based in Constantinople and its inhabitants were largely Orthodox Christian. Arab invaders from North Africa gradually conquered the island and forced many Christians to flee. One of them was a young man who would become known to history as Joseph the Hymnographer (c. 810-881). He joined a monastery in Thessalonica where he impressed his superiors who recommended that he take a post in the capital. After some years, he attempted a trip to Rome to speak to the pope on behalf of the pro-icon party which was being persecuted by the iconoclastic rulers, but was captured by pirates and spent time as a slave on Crete. After escaping (with the help of the ghost of St Nicholas who encouraged him to sing praises to God) he returned to Constantinople where he established a monastery; he again fell foul of the government and was sent into exile on the Crimean peninsula. When he returned he rose high in the ranks of the Orthodox Church.

Joseph is most famous as the composer of hundreds of hymns, some of them still in use today in Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant Churches. He is praised in an Orthodox hymn:

Come, let us acclaim the divinely inspired Joseph,

The twelve-stringed instrument of the Word,

The harmonious harp of grace and lute of heavenly virtues,

Who lauded and praised the assembly of the saints.

And now he is glorified with them.