Saint Edwin of Northumbria

Born a pagan, Edwin (585-633) became a Christian saint, the father of two saints, and the great-uncle and grandfather of two more saints.

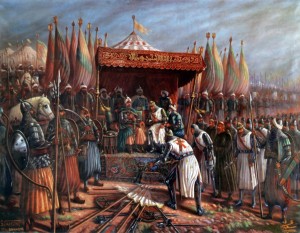

The political life of early medieval Britain was brutal, resembling in many ways A Game of Thrones, though with, perhaps, slightly less sex and no dragons. A number of minor, pagan Anglo-Saxon kingdoms continually struggled against each other, against native Christian enclaves and against raiders from Ireland and Caledonia. These statelets rose and fell, occasionally producing a ruler who was strong enough to dominate his neighbours for a time and earn the title of Bretwalda or High King. One of these was a northern prince named Edwin of Northumbria.

Edwin appeared at a time when Christian missions were penetrating these pagan Germanic territories from the north, where Irish-trained monks brought a Celtic Christianity and from the south, where missionaries had been sent from Catholic Rome. In 627, under the influence of Catholic bishop Paulinus, Edwin agreed to convert from his pagan upbringing. Bede’s history tells us that the king and his nobles debated the opportunity of becoming Christians, with the speech of one of his men being decisive:

The present life of man, O king, seems to me, in comparison with that time which is unknown to us, like to the swift flight of a sparrow through the room wherein you sit at supper in winter amid your officers and ministers, with a good fire in the midst whilst the storms of rain and snow prevail abroad; the sparrow, I say, flying in at one door and immediately out another, whilst he is within is safe from the wintry but after a short space of fair weather he immediately vanishes out of your sight into the dark winter from which he has emerged. So this life of man appears for a short space but of what went before or what is to follow we are ignorant. If, therefore, this new doctrine contains something more certain, it seems justly to deserve to be followed.

Edwin’s conversion and his domination of northern England aroused enemies, particularly the very able and aggressive Penda, the pagan king of Mercia. In 633 Penda defeated Edwin, killing him and his two sons. His Christian wife and Paulinus fled south and the Christian project in northern England suffered a temporary set-back.