Action-packed Christmas Days during the Late Middle Ages, 1250-1500.

• 1261 Having driven the Latin knights out of Constantinople, Byzantine emperor Michael VIII blinds rival John IV Lascaris whose 11th birthday it is. The boy will become a monk and be recognized as a saint. The Patriarch of Constantinople will excommunicate Michael. In 1284 Michael’s son, Andronikos II Palailogos will visit John and apologize.

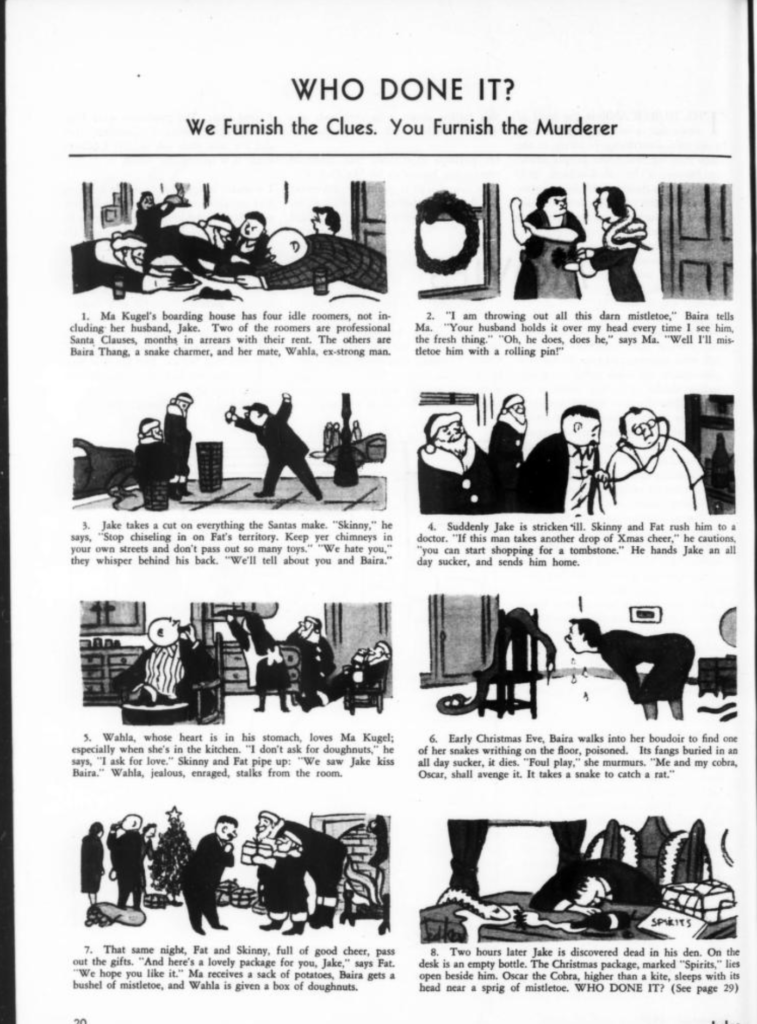

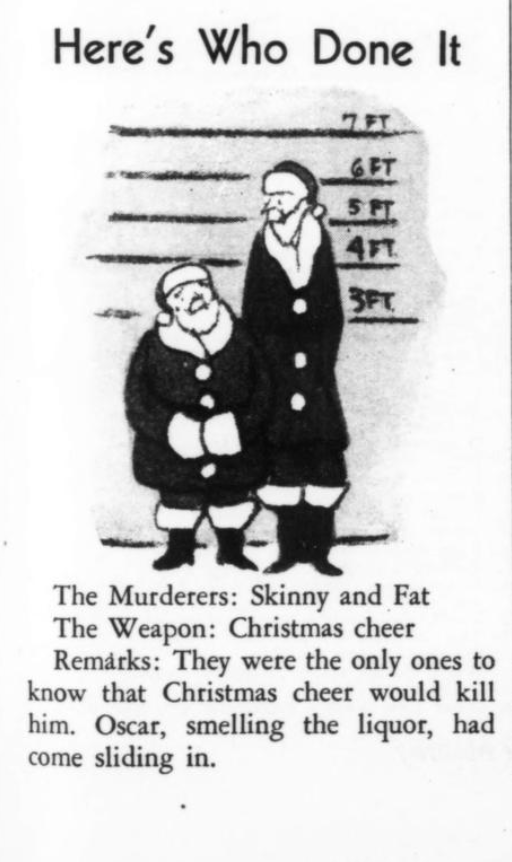

• 1287 A murder in Shropshire: John de Quercubus of Scottes Acton killed Hugh de Weston, chaplain, in self defence. On Christmas day 16 Edward I [1287] after sunset there were some men singing outside a tavern kept by Richard son of William de Skottesacton in that town. And Hugh came by the door immensely drunk, and quarrelled with the singers. Now John was standing by, singing, and Hugh hated him a little because he sang well, and desired the love of certain women who were standing by in a field and whom Hugh much affected. So Hugh took a naked sword in his hand and ran at John, striking him once, twice, thrice, on the head, and nearly cutting off two fingers of his left hand. And John went on his knees, and raised his hands asking God’s peace and the king’s, and then ran into a corner near the street under a stone wall. And Hugh ran after him and tried to kill him, so he drew his knife and wounded Hugh in the chest, killing him instantly.

• 1309 Pope Clement V has moved the papacy from Rome and spends his first Christmas in the Holy See’s new location in Avignon.

• 1349 The bubonic plague, Black Death, continues to ravage western Europe. A young Irishman writes: One thousand three hundred and fifty years from the birth of Christ till this night: and this is the second year since the coming of the plague into Ireland. I have written this in the twentieth year of my age. I am Hugh, son of Conor MacEagen, and whosoever reads it let him offer a prayer of mercy for my soul. This is Christmas night, and I place myself under the protection of the King of heaven and earth, beseeching that He will bring me and my friends safe through this plague. Hugh, son of Conor MacEagan, who wrote this in his father’s book in the year of the great plague.

• 1391 A dolphin “came foorth of the Sea and played himselfe in the Thames at London to the bridge.” John Stowe in his Annals goes on to say ” the which dolphin, being seen of the citizens and followed, was with much difficulty intercepted and brought again to London, showing a spectacle to many of the height of his body, for he was ten foot in length. These dolphins are fishes of the sea, that follow the voices of men, and rejoice in playing of instruments, and are wont to gather themselves at music. These, when they play in rivers, with hasty springings or leapings, do signify tempests to follow. The seas contain nothing more swift or nimble, for oftentimes with their skips they mount over the sails of ships.”

• 1400 Henry IV keeps Christmas at Eltham Palace where 12 aldermen of London and their sons ride in a mumming for the entertainment of the king and the visiting Byzantine emperor, Manuel II Palaiologos who has come seeking aid against the Turks. This was the first visit by a Roman emperor to England since the 4th century. Manuel will be given financial assistance but no military support.

Skirmishes take place in Syria between the Egyptian Mamluk army and forces of the Mongol invader Tamerlane.

• 1429 Joan of Arc spends Christmas at the Dauphin Charles’ court at Bourges. He gives her and her family the right to a coat of arms with the royal lilies of France.

• 1430 Joan of Arc is imprisoned in a tower at Rouen.

• 1444 London streets are wreathed with greenery: “Against the feast of Christmas every man’s house, as also the parish churches, were decked with holm, ivy, bays, and whatsoever the season of the year afforded to be green. The conduits and standards in the streets were likewise garnished” including, at the Leadenhall in Cornhill, “a standard of tree being set up in midst of the pavement, fast in the ground, nailed full of holm and ivy, for disport of Christmas to the people.” At the end of the Christmas season the latter will “torn up, and cast down by the malignant spirit (as was thought), and the stones of the pavement all about were cast in the streets, and into divers houses, so that the people were sore aghast of the great tempests.”

• 1492 Christopher Columbus’s ship “Santa Maria” runs aground on Hispaniola and has to be abandoned. Columbus writes in his log: I sailed in a slight wind yesterday and at the passing of the first watch, 11 o’clock at night …I decided to lie down to sleep because had not slept for two days and one night. Since it was calm, the sailor who was steering the ship also decided to catch a few winks and left the steering to a young ship’s boy…. I felt secure from shoals and rocks…. Our Lord willed that at midnight, when the crew saw me lie down to rest and also saw that there was a dead calm and the sea was as 25 in a bowl, they all lay down to sleep and left the helm to that boy. The currents carried the ship upon one of these banks…. Although there was little or no sea, I could not save her. A fort is built with the ship’s timbers. It is named Fuerte Navidad (Christmas Fort), the first Spanish settlement in the Americas.