1936

First elections to the Baseball of Fame

These are the five members of the Hall’s first class:

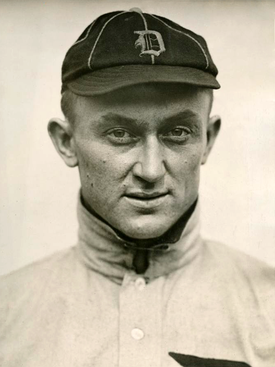

Ty Cobb, centre field, Detroit Tigers, the “Georgia Peach”, notoriously aggressive player. Averaged .367, 4,191 hits, 117 HR (“dead ball” era), 1,938 RBI, 897 stolen bases.

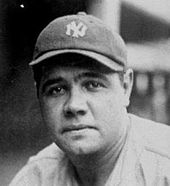

Babe Ruth, right field, New York Yankees; the “Bambino”, the “Sultan of Swat”; began as an excellent pitcher for the Red Sox, twice won 23 games, a 94-46 record with 2.28 ERA. Legendary home run hitter, .342 average, 2,873 hits, 714 HR, 2,213 RBI.

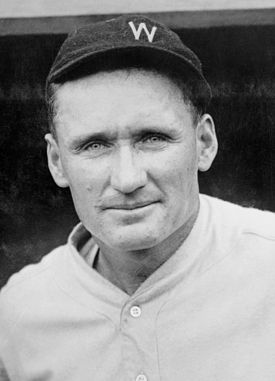

Walter Johnson, pitcher, Washington Senators, the “Big Train”. 417-279, 2.17 ERA, 3,508 strike-outs, 110 shut-outs.

Christy Mathewson, pitcher, New York Giants; the “Christian Gentleman” who never pitched on Sunday. 373-188 record, 2.13 ERA, 2,502 strike-outs.

Honus Wagner, shortstop, Pittsburgh Pirates; the “Flying Dutchman”, the greatest fielder of his generation and a superb base runner and hitter. Batted .329, with 3, 430 hits, 101 home runs (in the “dead ball” era), 1,732 RBI, and 722 stolen bases.