1469

Birth of Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) was a Florentine politician and writer whose name has become synonymous with the publication of the deeply-cynical The Prince but who had a much more interesting career than merely writing a tract on a conscience-free approach to public life. Of him, Chamber’s Book of Days says:

Machiavelli was born, in Florence, in 1469, of an ancient, but not wealthy family. He received a liberal education, and in his 29th year he was appointed secretary to the Ten, or committee of foreign affairs for the Florentine Republic. His abilities and penetration they quickly discerned, and despatched him from time to time on various and arduous diplomatic missions to the courts and camps of doubtful allies and often enemies. The Florentines were rich and weak, and the envy of the poor and strong; and to save themselves from sack and ruin, they had to trim adroitly between France, Spain, Germany, and neighbouring Italian powers. Machiavelli proved an admirable instrument in such difficult business; and his despatches to Florence, describing his own tactics and those of his opponents, are often as fascinating as a romance, while furnishing authentic pictures of the remorseless cruelty and deceit of the statesmen of his age.

In 1512 the brothers Giuliano and Giovanni de Medici, with the help of Spanish soldiers, re-entered Florence, from which. their family had been expelled in 1494, overthrew the government, and seized the reins of power. Machiavelli lost his place, and was shortly after thrown into prison, and tortured, on the charge of conspiring against the new regime. In the meanwhile Giovanni was elected Pope by the name of Leo X; and knowing the Medicean love of literature, Machiavelli addressed a sonnet from his dungeon to Giuliano, half sad, half humorous, relating his sufferings, his torture, his annoyance in hearing the screams of the other prisoners, and the threats he had of being hanged. In the end a pardon was sent from Rome by Leo X, to all concerned in the plot, but not until two of Machiavelli’s comrades had been executed.

Machiavelli now retired for several years to his country-house at San Casciano, about eight miles from Florence, and spent his days in literary pursuits. His exile from public life was not willing, and he longed to be useful to the Medici. Writing to his friend Vettori at Rome, 10th December, 1513, he says, ‘I wish that these Signori Medici would employ me, were it only in rolling a stone. They ought not to doubt my fidelity. My poverty is a testimony to it.’ In order to prove to them ‘that he had not spent the fifteen years in which he had studied the art of government in sleeping or playing,’ he commenced writing The Prince, the book which has clothed his name with obloquy. It was not written for publication, but for the private study of the Medici, to commend himself to them by proving how thoroughly he was master of the art and craft of Italian statesmanship.

About 1519 the Medici received him into favour, and drew him out of his obscurity. Leo X employed him to draw up a new constitution for Florence, and his eminent diplomatic skill was brought into play in a variety of missions. Returning to Florence, after having acted as spy on the Emperor Charles V’s movements during his descent upon Italy, he took ill, and doctoring himself, grew worse, and died on the 22nd of June, 1527, aged fifty-eight. He left five children, with little or no fortune. He was buried in the church of Santa Croce, where, in 1787, Earl Cowper erected a monument to his memory.

The Prince was not published until 1532, five years after Machiavelli’s death, when it was printed at Rome with the sanction of Pope Clement VII; but some years later the Council of Trent pronounced it ‘an accursed book.’ The Prince is a code of policy for one who rules in a State where he has many enemies; the case, for instance, of the Medici in Florence. In its elaboration, Machiavelli makes no account of morality, probably unconscious of the principles and scruples we designate by that name, and displays a deep and subtle acquaintance with human nature. He advises a sovereign to make himself feared, but not hated; and in cases of treason to punish with death rather than confiscation, ‘for men will sooner forget the execution of their father than the loss of their patrimony.’

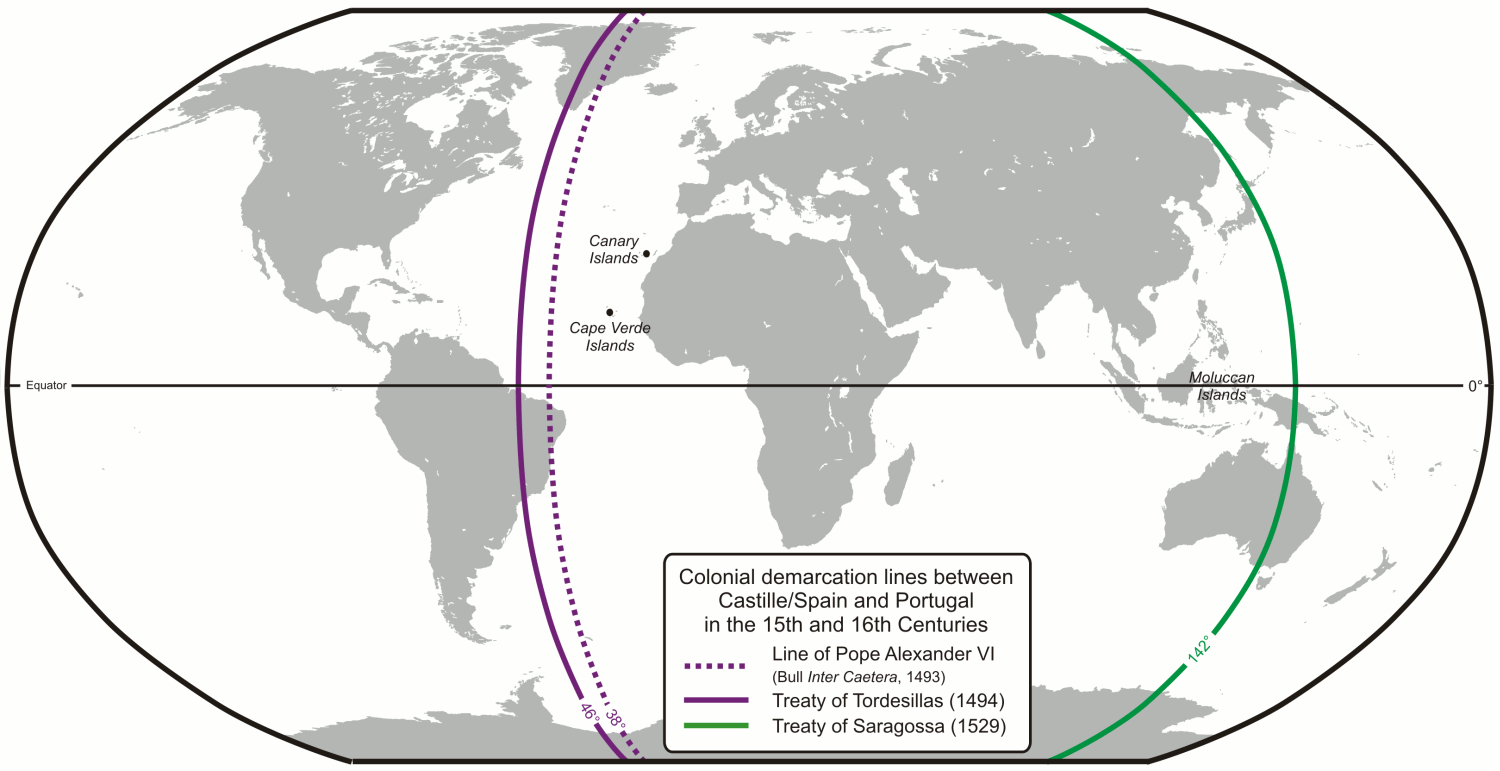

There are two ways of ruling, one by the laws and the other by force: ‘the first is for men, the second for beasts;’ but as the first is not always sufficient, cient, one must resort at times to the other, ‘and adopt the ways of the lion and the fox.’ The chapter in which he discusses, ‘in what manner ought a prince to keep faith?’ has been most severely condemned. He begins by observing, that everybody knows how praiseworthy it is for a prince to keep his faith, and practise no deceit; but yet, he adds, we have seen in our own day how princes have prospered who have broken their faith, and artfully deceived their rivals. If all men were good, faith need never be broken; but as they are bad, and will cheat you, there is nothing left but to cheat them when necessary. He then cites the example of Pope Alexander VI as one who took in everybody by his promises, and broke them without hesitation when he thought they interfered with his ends.

It can hardly excite wonder, that a manual of statesmanship written in such a strain should have excited horror and indignation throughout Europe. Different theories have been put forth concerning The Prince by writers to whom the open profession of such deceitful tactics has seemed incredible. Some have imagined, that Machiavelli must have been writing in irony, or with the purpose of rendering the Medici hateful, or of luring them to destruction. The simpler view is the true one: namely, that he wrote The Prince to prove to the Medici what a capable man was resting idly at their service. In holding this opinion, we must not think of Machiavelli as a sinner above others. He did no more than transcribe the practice of the ablest statesmen of his time into luminous and forcible language. Our feelings of repugnance at his teaching would have been incomprehensible, idiotic, or laughable to them. If they saw any fault in Machiavelli’ s book, it would be in its free exposure of the secrets of statecraft.

Unquestionably, much of the odium which gathered round the name of Machiavelli arose from that cause. His posthumous treatise was conveniently denounced for its immorality by men whose true aversion to it sprang from its exposure of their arts. The Italians, refined and defenceless in the midst of barbarian covetousness and power, had many plausible excuses for Machiavellian policy; but every reader of history knows, that Spanish, German, French, and English statesmen never hesitated to act out the maxims of The Prince when occasion seemed expedient. If Machiavelli differed from his contemporaries, it was for the better. Throughout The Prince there flows a hearty and enlightened zeal for civilization, and a patriotic interest in the welfare of Italy. He was clearly a man of benevolent and honourable aims, but without any adequate idea of the wrongfulness of compassing the best ends by evil means. The great truth, which our own age is only beginning to incorporate into statesmanship, that there is no policy, in the long run, like honesty, was far beyond the range of vision of the rulers and diplomatists of the 15th and 16th centuries.

Machiavelli was a writer of singularly nervous and concise Italian. As a dramatist he takes high rank. His comedy of Mandragola is spoken of by Lord Macaulay as superior to the best of Goldoni, and inferior only to the best of Molière. It was performed at Florence with great success and Leo X admired it so much, that he had it played before him at Rome. He also wrote a History of Florence, which is a lively and graphic narrative, and an Art of War, which won the praise of so competent a judge as Frederick the Great of Prussia. These and other of his works form eight and ten volumes octavo in the collected editions.