1520

Massacre at a Mexican Festival

In 1519 the Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortes had succeeded in invading the Aztec empire of central Mexico and controlling the Aztec emperor, Moctezuma, and the capital Tenochtitlan. Relations between the tiny Spanish contingent and the mass of Aztecs was tense and the deeds of this day in 1520 brought things to a boiling point.

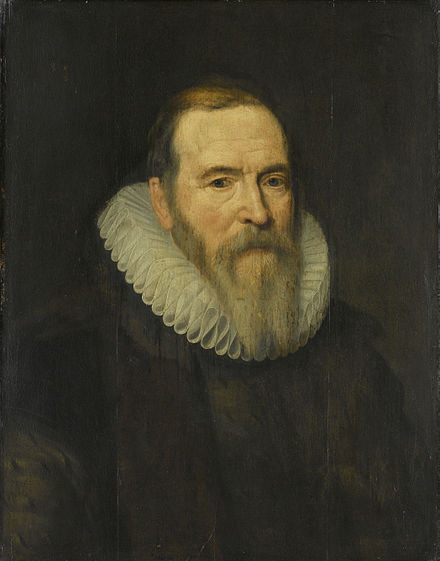

Cortes had departed Tenochtitlan to head for the coast where he expected to battle some other Spaniards with orders to arrest him. He had left in charge his unstable deputy Pedro de Alvarado (shown above). During the absence of Cortes, Alvarado was approached by high-ranking Aztecs who wished to hold a festival and sought his permission lest he think they were gathering with hostile intent. Alvarado agreed, provided there would be no human sacrifice involved (a ritual that marked many Aztec festivals). When Alvarado learned that the celebrations would, in fact, include a human sacrifice he acted to halt it and massacred the participants.

That was the Spanish story. Here is the Aztec account:

- Here it is told how the Spaniards killed, they murdered the Mexicans who were celebrating the Fiesta of Huitzilopochtli in the place they called The Patio of the Gods

- At this time, when everyone was enjoying the celebration, when everyone was already dancing, when everyone was already singing, when song was linked to song and the songs roared like waves, in that precise moment the Spaniards determined to kill people. They came into the patio, armed for battle. They came to close the exits, the steps, the entrances [to the patio]: The Gate of the Eagle in the smallest palace, The Gate of the Canestalk and the Gate of the Snake of Mirrors. And when they had closed them, no one could get out anywhere.

- Once they had done this, they entered the Sacred Patio to kill people. They came on foot, carrying swords and wooden and metal shields. Immediately, they surrounded those who danced, then rushed to the place where the drums were played. They attacked the man who was drumming and cut off both his arms. Then they cut off his head [with such a force] that it flew off, falling far away. At that moment, they then attacked all the people, stabbing them, spearing them, wounding them with their swords. They struck some from behind, who fell instantly to the ground with their entrails hanging out [of their bodies]. They cut off the heads of some and smashed the heads of others into little pieces.

- They struck others in the shoulders and tore their arms from their bodies. They struck some in the thighs and some in the calves. They slashed others in the abdomen and their entrails fell to the earth. There were some who even ran in vain, but their bowels spilled as they ran; they seemed to get their feet entangled with their own entrails. Eager to flee, they found nowhere to go. Some tried to escape, but the Spaniards murdered them at the gates while they laughed. Others climbed the walls, but they could not save themselves. Others entered the communal house, where they were safe for a while. Others lay down among the victims and pretended to be dead. But if they stood up again they [the Spaniards] would see them and kill them.

- The blood of the warriors ran like water as they ran, forming pools, which widened, as the smell of blood and entrails fouled the air. And the Spaniards walked everywhere, searching the communal houses to kill those who were hiding. They ran everywhere, they searched every place.

- When [people] outside [the Sacred Patio learned of the massacre], shouting began, “Captains, Mexicas, come here quickly! Come here with all arms, spears, and shields! Our captains have been murdered! Our warriors have been slain! Oh Mexica captains, [our warriors] have been annihilated!”

- Then a roar was heard, screams, people wailed, as they beat their palms against their lips. Quickly the captains assembled, as if planned in advance, and carried their spears and shields. Then the battle began. [The Mexicas] attacked them with arrows and even javelins, including small javelins used for hunting birds. They furiously hurled their javelins [at the Spaniards]. It was as if a layer of yellow canes spread over the Spaniards.

This massacre led to a complete breakdown of trust between the Spanish and the Aztec rulers. Rebellion against Cortes broke out and horrible deeds ensued.